Natural Bodies, Ideal Shapes: The Hidden Geometry of Nature

Co-curated by Dr Laura Moretti (School of Art History, University of St Andrews) and Anna Venturini (MLitt Museum & Gallery Studies, University of St Andrews).

The exhibition presents a blend of human artefacts and natural elements that illustrate how basic principles of sciences such as Geometry and Mathematics are also to be found in Nature. Many species of flowers and leaves resemble geometrical solids and figures, and we know symmetry plays a key role in determining the aspects of certain insects. However, this correspondence is most evident in the case of crystals and minerals, whose underlying geometrical architecture was noticed and recorded at an early stage by Medieval and Renaissance scholars.

Long believed to be a form of ice, crystals are elaborate constellations of atoms arranged in microscopic combinations in ways that determine their outward shape. Their complexity varies greatly, ranging from simple solids with three or four faces, to bewildering specimens featuring more than twenty facets and angles.

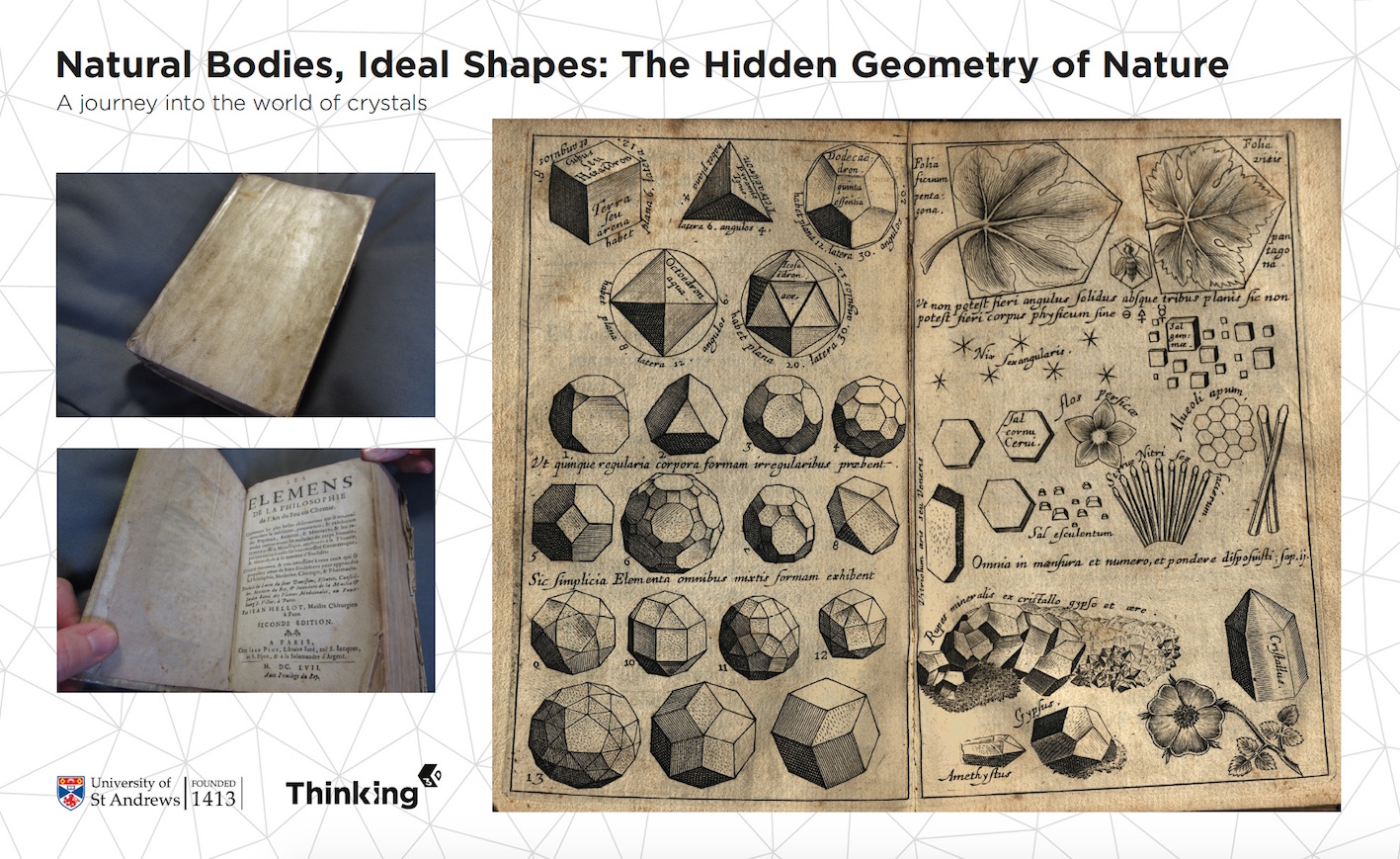

It is this complexity which is captured in the reproductions of two printed pages that line the cabinet. They come from the 1657 French translation of Philosophia Pyrotechnica, a Latin textbook written by the Scottish scholar, William Davidson, one of the first professors of chemistry in Europe and an advocate of ‘Paracelsianism’, a comprehensive medical philosophy which offered an alternative to the traditional therapeutic system by promoting the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine.

On the left-hand side, crystals are differentiated in terms of their geometrical structure. Until the early twentieth century, their internal molecular form could only be studied using so-called ‘polyhedra’. These are idealised crystal models with equally developed facets that were first used in the late eighteenth century.

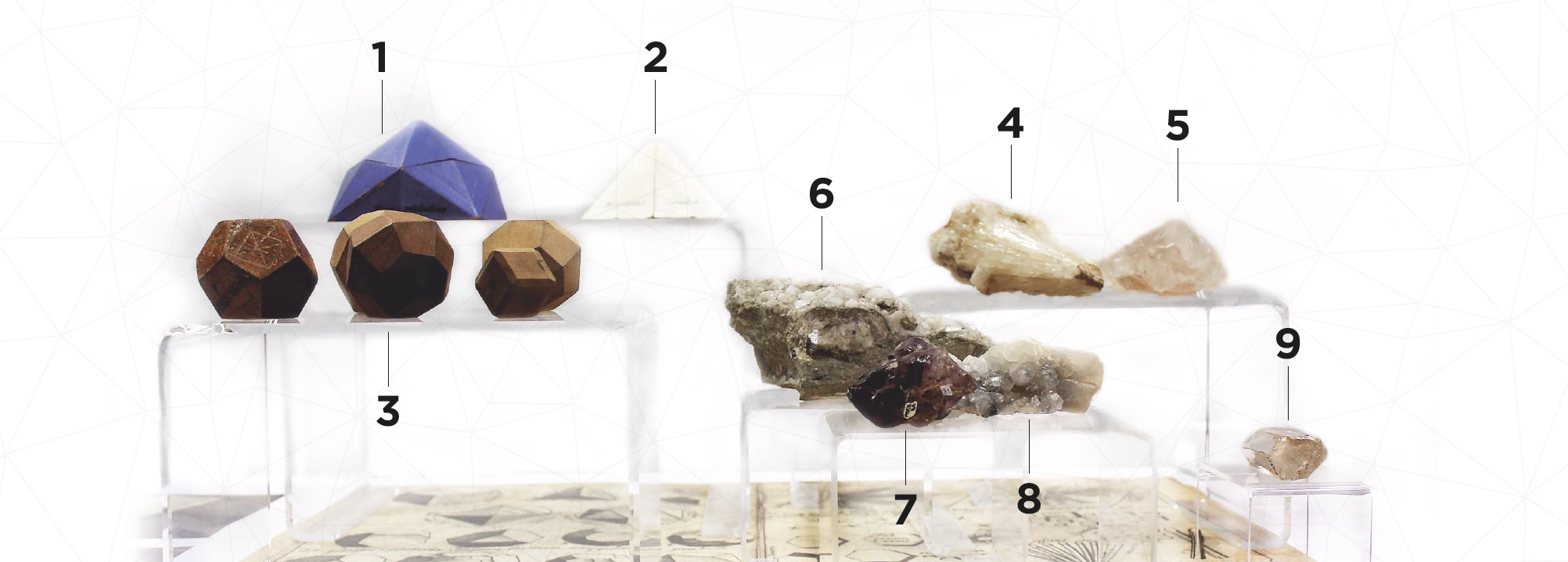

A few of these basic models, which are made of wood, are displayed in the cabinet, together with two slightly larger coloured models. These objects recount the fascinating story of the evolution of crystallography in the nineteenth century. Most likely used for teaching purposes at the University of St Andrews, they were meant to illustrate how the outward appearance of crystals (their facets) perfectly mirror their hidden internal structure. Despite the wealth of digital technologies available today, similar wooden models are still used by lecturers in the School of Earth & Environmental Sciences to teach students how to recognise and classify different types of crystals.

- Hexa-Octahedron model (nineteenth century, University Collections)

- White Bipyramidal Dodecahedron model (nineteenth century, University Collections)

- Crystal models made from wood (nineteenth century, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences)

- Thompsonite (School of Earth and Environmental Sciences)

- Cubic Halite – Rock Salt (School of Earth and Environmental Sciences)

- Harmotone (School of Earth and Environmental Sciences)

- Amethyst (School of Earth and Environmental Sciences)

- Calcite (School of Earth and Environmental Sciences)

- Quartz (University Collections)

On the right-hand side of the plate from Davidson’s book, geometry meets the natural world to give birth to the existing crystals and minerals faithfully reproduced on the page. Through a selection of specimens ranging from well-known crystals like Amethyst and Quartz, to lesser-known names such as Harmotone and Thompsonite, we wish to portray the beauty and variety of these intricate shapes, which harmoniously weave together the pure concepts and abstractions of Mathematics with the mesmerising phantasy and creativity of Nature.

You can read more about crystals and the beginnings of modern crystallography on the Museum of the University of St Andrews Collections Blog.

The exhibition is supported by Thinking 3D.

The curators wish to thank Jessica Burdge and Louise Hanwright (Museums & Collections), Erica Kotze and Gabriel Sewell (Library, Special Collections), Stuart Allison (School of Earth & Environmental Sciences), Leo Mewse (Print & Design), and Andrew Demetrius (School of Art History) for their support.