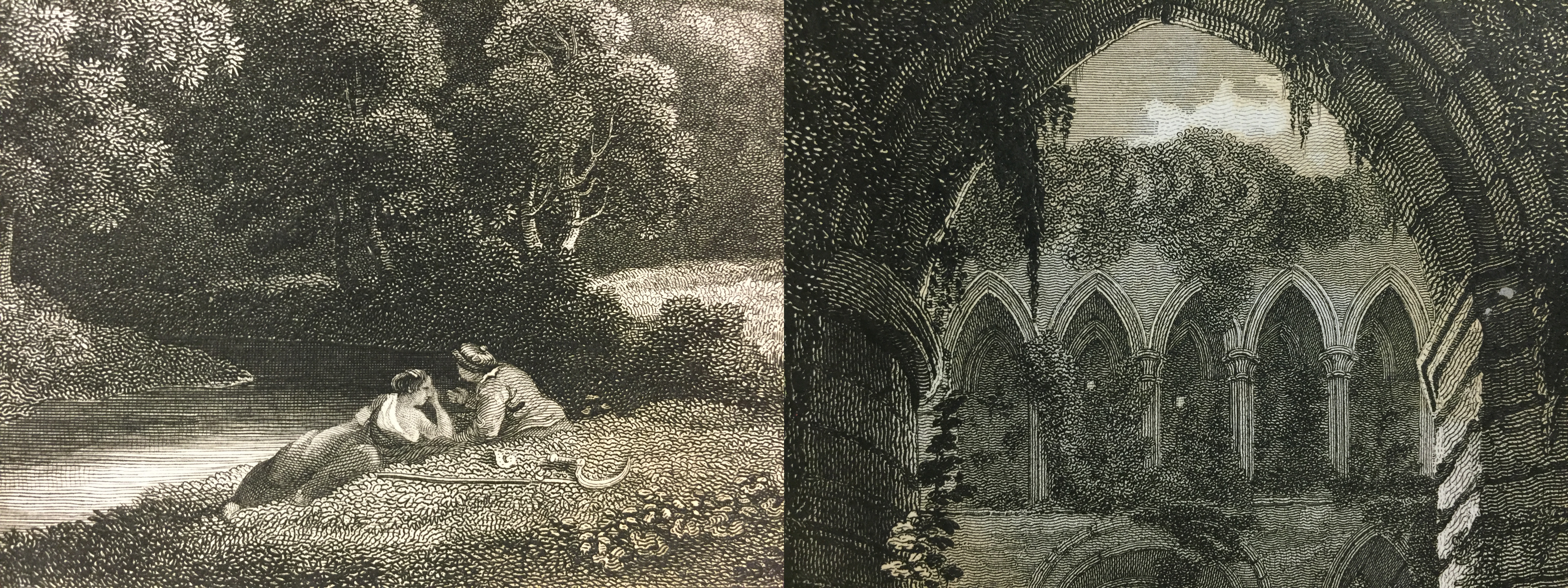

Translating three-dimensional structures into two-dimensional engravings has long been a particular challenge for artists and artisans attempting to depict architectural subjects on paper – a challenge particularly acute in the early nineteenth-century, the period preceding the rise of photography, when there was a growing desire for empirical and illusionistic representations of the natural world. Many such illustrations, claiming to present a truthful window onto nature, offered detailed, naturalistic representations that were nonetheless embroidered with romanticising flourishes.

The first volume of The Border Antiquities of England and Scotland was initially published in 1814, co-authored by John Greig and William Mudford, with contributions from Sir Walter Scott in the 1817 publication, notably in the substantial introductory essay. The book is a survey of “specimens of architecture and sculpture, and other vestiges of former ages” from the border regions of Scotland and England with historical descriptions accompanied by Greig’s engravings. The illustrations prioritise the empirical details of the architecture, monuments and objects discussed in the text, but at the same time, in a typically nineteenth-century fashion, they contextualise the historical monuments within romanticised landscapes.

Scott was a poet and novelist, renowned for the creation of the historical novel, a genre that mixes history with romance, beginning with the publication of Waverly in 1814. This literary hybrid of truth to nature and fantasy is also reflected in the engravings for this text. Having spent much of his childhood in Sandyknowe, Scott developed a lifelong interest in the folk traditions of the Border regions collecting Border ballads, publishing The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. It is not surprising that he was part of the publication of this book, despite the fact that contemporary reviewers point out that he did not take much part in the publication and Scott himself said it to be a “foolishly conducted publication”.

Capturing the historic buildings and sculptures in as much detail as possible, the images present complex three-dimensional structures in all of their depth and detail using only lines and hatching on a two-dimensional frame. Paying minute attention to the damage on the structures, the weathering, and the differing textures of building materials, these engravings are executed with scientific precision, but without the flatness and sterility of a diagram.

Not only do the engravings present clean and clear renderings of the structures described in the text, they also incorporate elements of the same romanticism that infuses Scott’s literature. Almost every one of Greig’s illustrations incorporates staffage, which gives a sense of scale and depth, whilst also an adding allegorical side notes to each illustration. The figures serve a dual purpose, technical and aesthetic, directing the viewer’s eye to significant points in the image while also creating a romantic context for the scene. A natural abundance is emphasised in each engraving with lush trees and shrubbery framing the historical monuments within a romantic landscape while also acting as a device to create atmospheric recession. Greig even includes incidental details like birds over water and interactions between figures which also help to create the sense that the scene captures a specific place and time. In contextualising the scenes for the viewer, these stylistic elements aid in the struggle towards achieving the illusion of three-dimensional space on the two-dimensional surface.

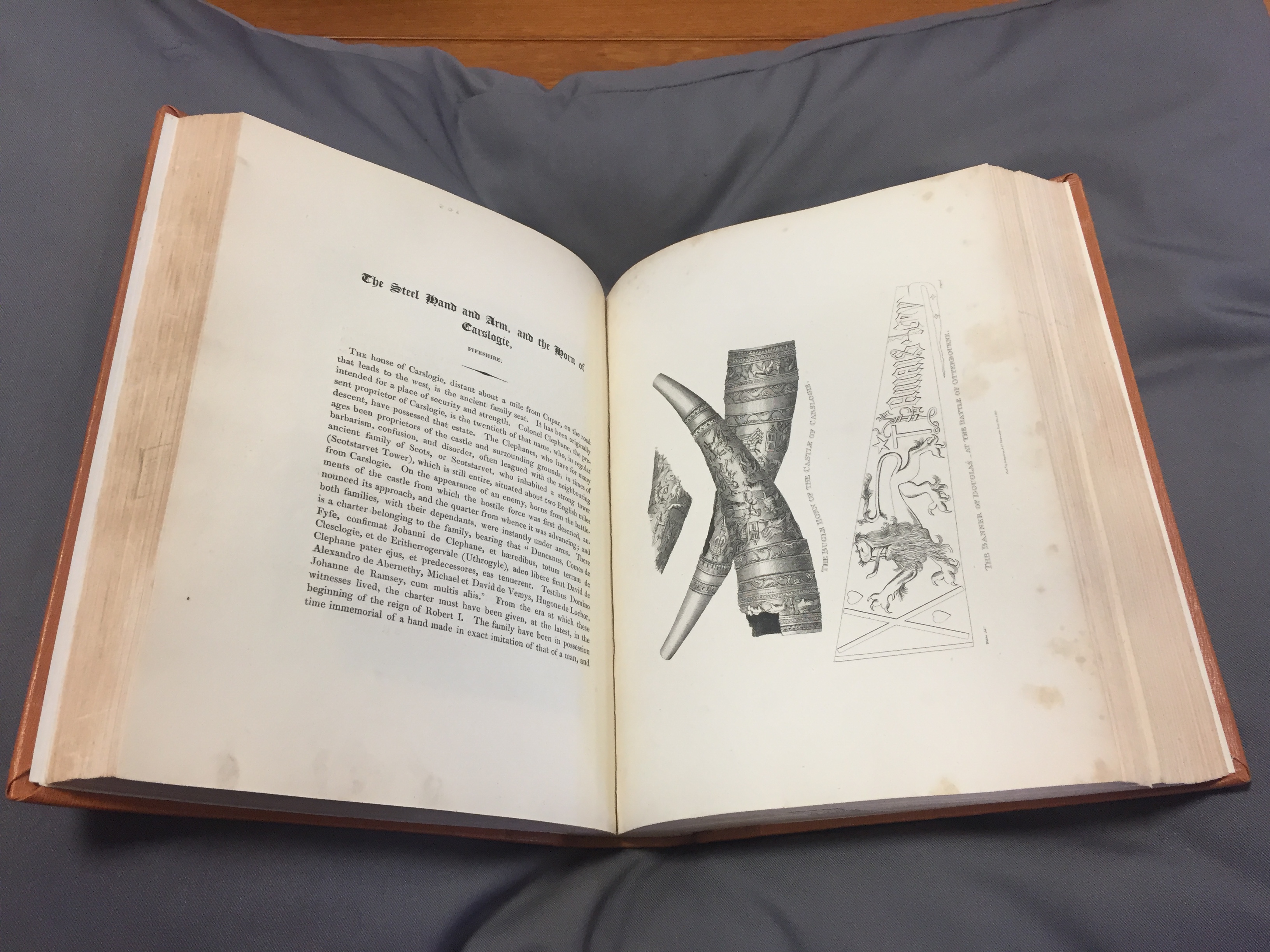

Toward the end of the first volume, two diagrams appear that deviate from the illusionistic and illustrative engravings that dominate the book. The objects depicted – “The Steel Hand and Arm, and the Horn of Carslogie” –are significant to the history of Scotland. The diagram of the horn is placed against white space as opposed to recessional space, no longer presented as a window onto life. These diagrams emphasise the priority that empirical detail holds in the book while also representing a different way in which three-dimensional objects can be presented to the viewer.

Lucy Howie, Sabrina Hamilton, Esther Simon