Nowadays we are all familiar with those children’s books in which figures are made by several flaps of paper superimposed over each other. Some of us might have even experienced that feeling of trepidation which precedes the unveiling of the figures’ hidden secrets, as the flaps are lifted one by one.

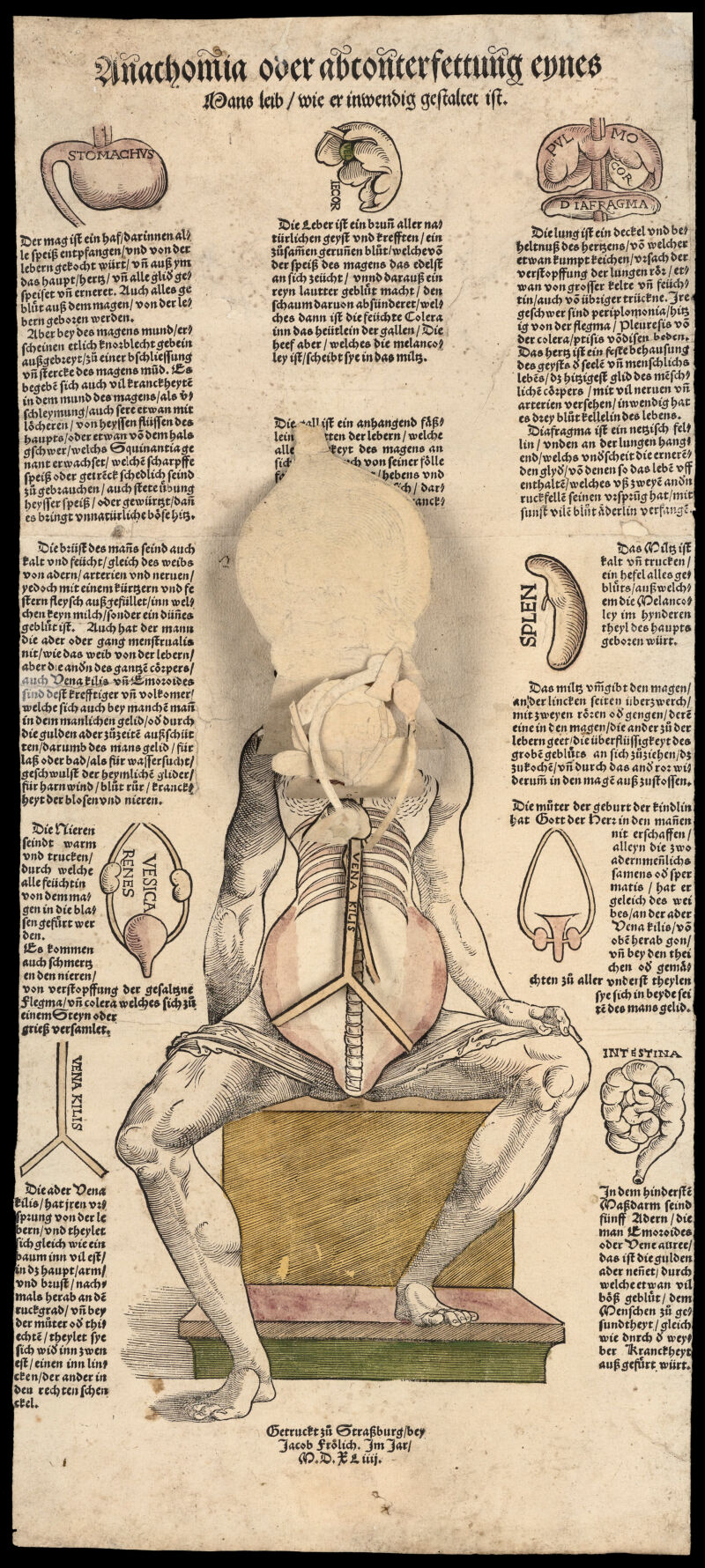

What many of us might not expect, however, is that lift-the-flap books are just the last heirs of a long-standing tradition, harking back to sixteenth-century Germany. Here, in 1538, Jobst de Negker – a block-cutter and print publisher from Augsburg – printed what is probably the forefather of all modern lift-the-flap books, a single-sheet woodcut illustrating the anatomy of the female body with the aid of superimposed engraved flaps (Anathomia oder abconterfectung eines Weybs leyb wie er innwendig gestaltet ist).

The following year Negker issued as well a bilingual copy of Andrea Vesalius’s Tabulae Anatomicae, in order to make them accessible to German students struggling with Latin. Vesalius’s tables had themselves been conceived as anatomical fugitive sheets, aimed at providing students with a simplified version of traditional medicine, but it was thanks to Negker’s superimposed flaps that fugitive sheets truly became a means of disseminating elementary medical knowledge amongst a wider, nonspecialist public. Flap after flap, in a much more playful way, ordinary people could as well be initiated to the secrets of the inner human body, whose three-dimensionality was recreated by the sequence of layers.

These fugitive sheets with superimposed flaps continued to circulate in Europe for centuries, giving birth to a whole literary sub-genre featuring works like Hans Guldenmundt’s Ausslegung undbeschreybung der Anatomi (1539), the French, Flemish and Latin editions of anatomical sheets printed by Sylvestre de Paris (1540-45) and Alain La Mathonière’s French reprint of Guldenmundt’s sheets (1560).

In Negker’s woodcut, the internal organs are printed on separate sheets, cut out and glued together. The image prevails over the German text, nothing more than a simplified description of the organs’ physiology and nature. Centuries before the advent of technology and virtual reality, this amazing woodcut offers a fascinating example of how the medium of paper, traditionally bi-dimensional, could be played with to cast the illusion of a three-dimensional space to be explored, as a surgeon would have done with a real body.

Interactive item with moveable parts of a 1539 reprint preserved at Duke University Libraries available at: here. Full catalogue record available here