Jean Poldo d’Albenas, a lawyer, was as keen on antique architecture as his father, who, when he was first consul of Nîmes had taken the initiative to preserve numerous architectural vestiges of the city by moving them to the Porte de la Couronne. For once the French were not neglecting their antique heritage. In 1559 (the date when a few copies were printed) and in 1560 he published a fine book in a folio format at the print shop of Guillaume Roville in Lyon, the Discours historial de l’antique et illustre cité de Nismes, which on first sight can have certain similarities to several publications devoted to “the antiquity” of a kingdom, a province, or, as here, of a city (Fig. 1).

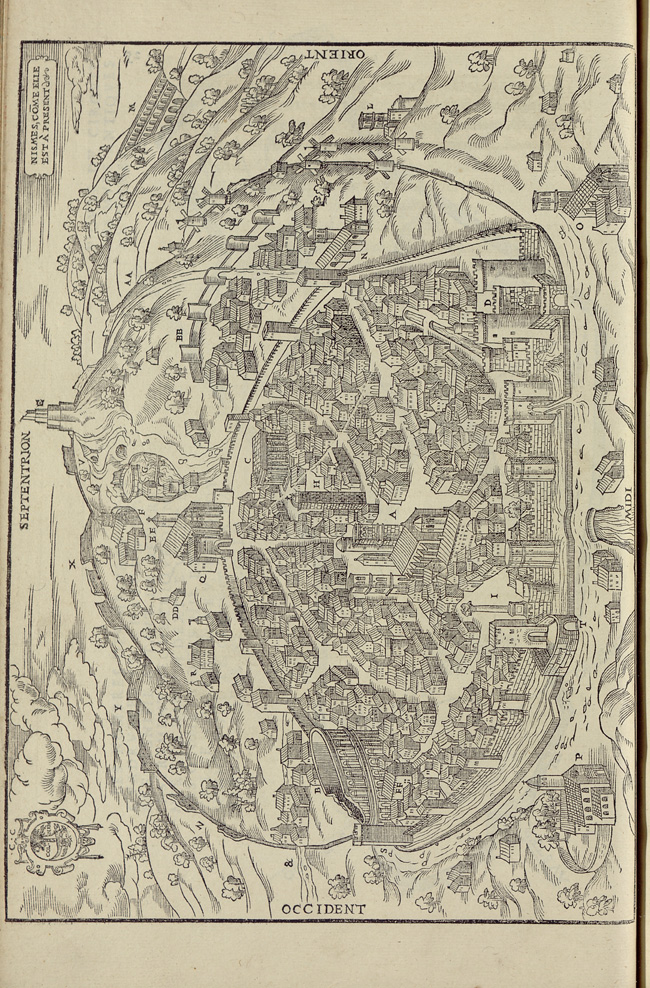

For once Nîmes could be proud of a prestigious Roman past attested by a quasi-intact amphitheatre and many other monumental vestiges, a dynastic temple (the Maison Carrée), a tower (the Tour Magne) which marked the Augusteum where the “temple of the Fountain” still remained, and an aqueduct of which large fragments existed (the Pont du Gard). But the book puts emphasis on monumental Roman architecture in the text as well as in the iconography. The oriented plan of the antique enclosure and the bird’s-eye view of the modern city appear in front, where one sees the antique edifices of the city shown to advantage free from any interfering constructions (Fig. 2).

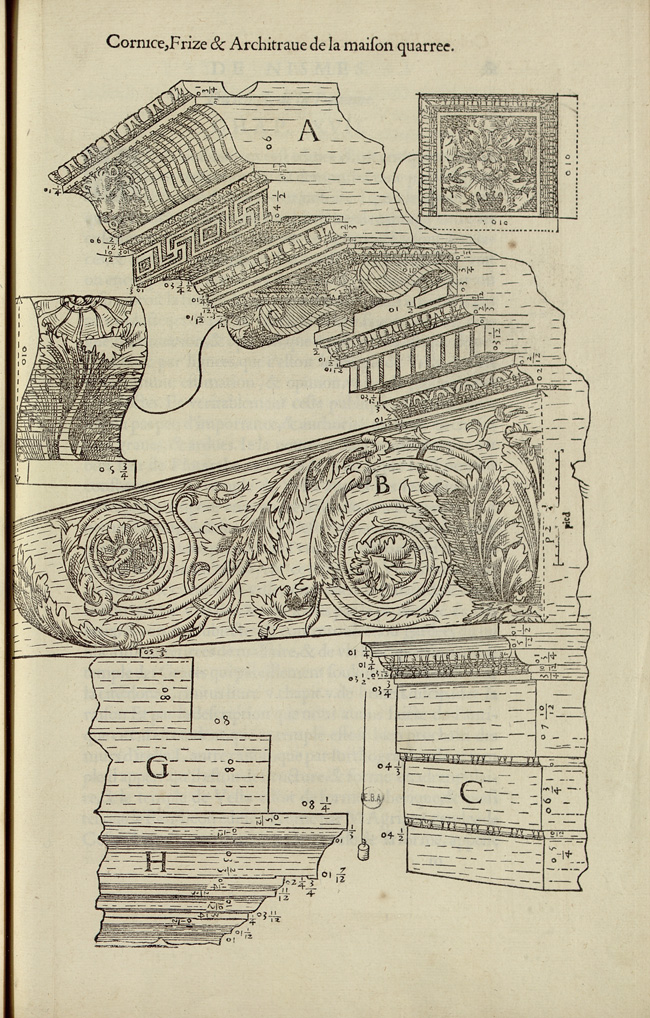

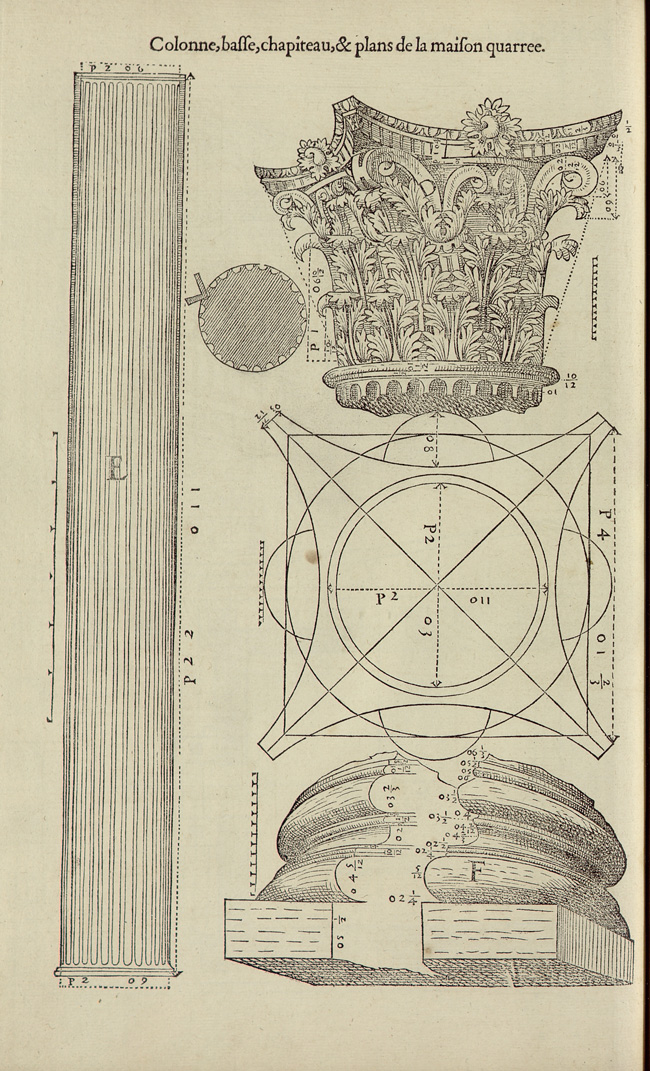

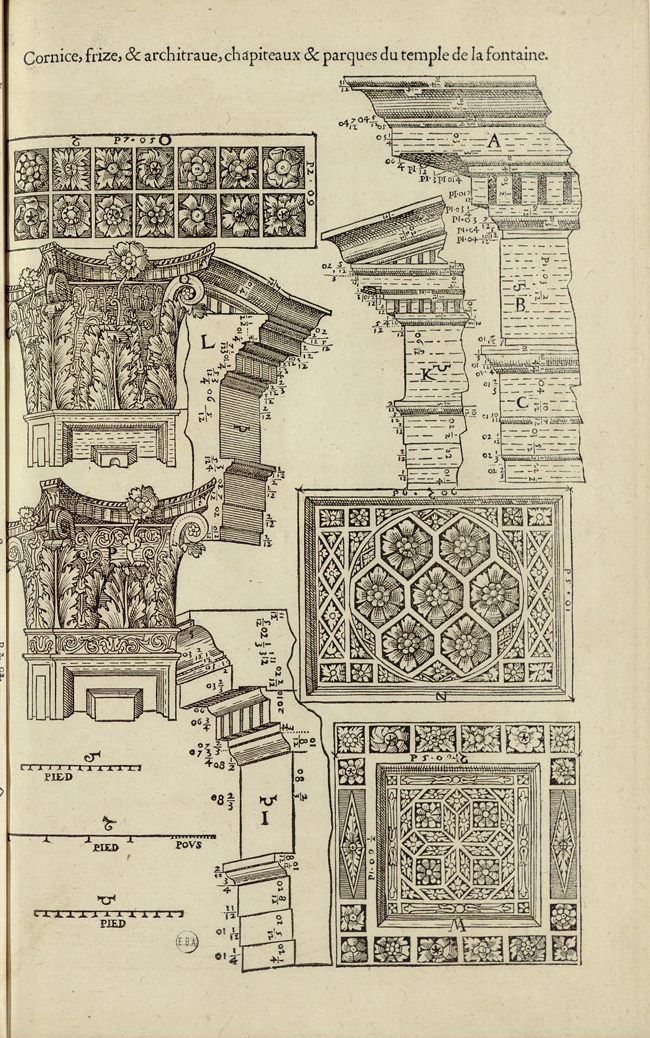

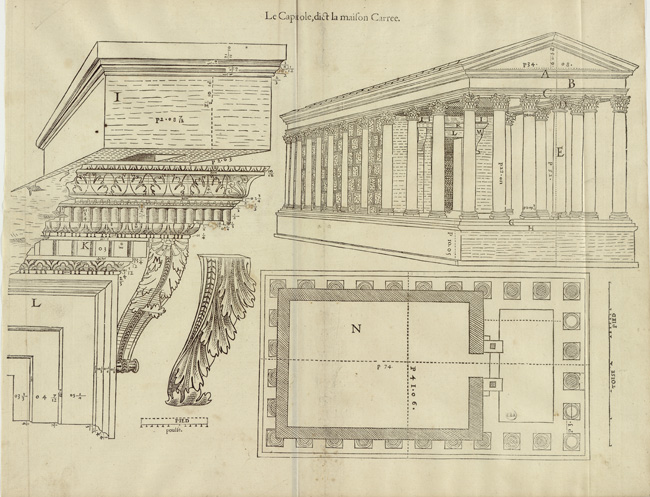

The chapters especially devoted to the Maison Carrée (chap. 16), the “temple of the Fountain” (chap. 17), the pont du Gard (chap. 18) as well as the amphitheatre (chap. 22), are accompanied by engraved plates and numbered captions (Fig. 3).

These are plans marked in inches, feet and toises representing the plan and the elevation of the monument as well as the details of the orders (bases, capitals and entablatures) in which each moulding is represented with its measurements. The illustrations of the Maison Carrée, the “temple of the Fountain” and the amphitheatre even more than those of the pont du Gard are not simply elevations in perspective but constitute the first architectural plans published in France, well ahead of the treatises of Bullant (1564) and Delorme (1567). This archeological vision, unique during the 1550s, indicates an astonishing familiarity with the Coner Codex, or a copy of it, which in its time had revolutionized architectural representation with diagonal perspective created in a cross-section. In this way the draughtsman presents the entablature of the Maison Carrée, the “temple of the Fountain” and the amphitheatre (Figs 4, 5).

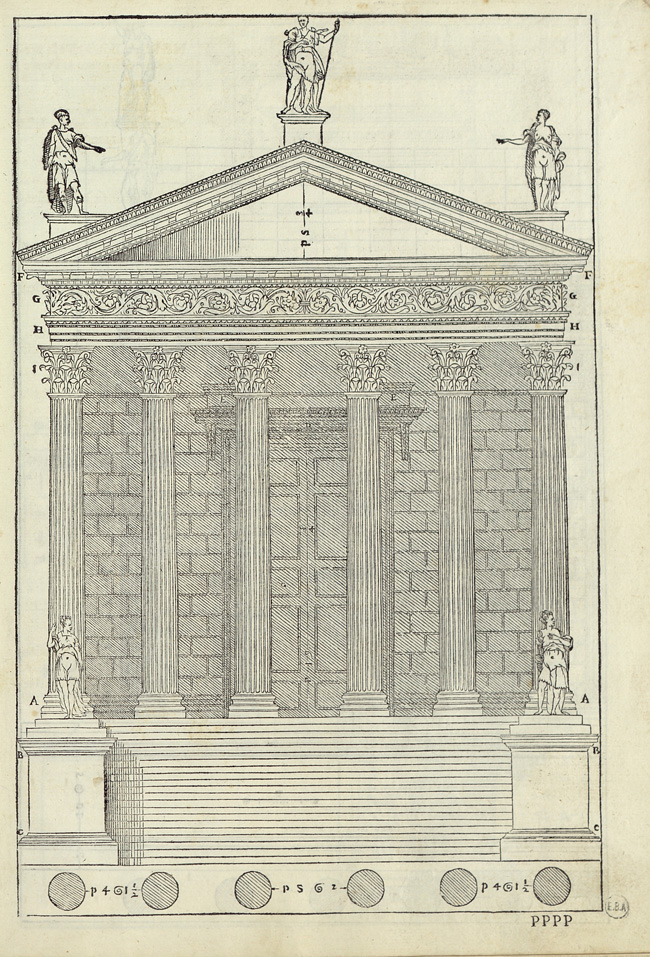

These are far from the representations of the amphitheatre and the Maison Carrée by Androuet du Cerceau from 1540-1550, which are more ideal than archeological, and far from recent Vitruvian literature which only illustrated theoretical models or which indicated proportions only. And if Serlio in 1540 and Delorme in 1567 relied only on oblique perspective, their plans have no written dimensions. The draughtsman even innovated by representing the Corinthian and composite capitals in a three-quarter view; in this instance this kind of representation is rather clumsy (Fig. 6).

In Italy the only equivalent book which preceded it was written by Torello Sarayna on Verona, with superb plates by Giovanni Caroto (De origine et amplitudine civitatis Veronæ, 1540). The Urbis Romæ Topographia by Marliani, even in its enlarged version of 1544, had few illustrations. As for Serlio’s book on Roman antiquities, the Terzo libro, published in 1540 in Venice, it is less a collection of precise architectural plans of ruins than a book of models, classified by type whose structures and ornaments are so many common assumptions to be amplified.

Here it is doubtless necessary to see the direct intervention of the bookseller Guillaume Roville (and not Rouillé) notwithstanding the undeniable architectural culture of Poldo d’Albenas who quotes Vitruvius, Alberti and especially Philandrier. The attention he brings to the orders and to their constituent parts down to the most minor mouldings, the iconography of the capitals, derives from a refined reading of the French theoretician. But although Poldo measured the enclosure of his native city himself and studied the main monuments in the field, he was neither a draughtsman nor an engraver ; it must be concluded that the text does not refer to the plates. Poldo recalls the history of each edifice, the origin of its name, its function, even its avatars. He develops the description of the amphitheatre rather briefly, as if the image, more explicit than the text, was more important. However we know that Roville personally oversaw the illustrations of the books he printed. Trained in Venice, he retained close links with the Most Serene Republic whose market he watched over. Perhaps he wanted to compete with his Veronese colleague Antonio Putelletto, who had published Sarayna’s book on Verona and himself ordered architectural plans of the antiquities in Nîmes from an Italian artist.

In fact it was the plates of the Discours historial which attracted readers’ attention. Palladio was not mistaken when he was inspired by the Discours historial for book IV of the Quattro libri dell’architettura where he includes the two temples in Nîmes among the most beautiful Roman achievements. The Italian architect, who never went to France, devoted six plates to the Maison Carrée and five to the “temple of the Fountain”, which he calls the temple of Vesta (Fig. 7).

Palladio could mine his source easily, convert the measurements and, as an alert antiquarian and professional, improve the perspective of the edifices. His knowledge of Roman imperial architecture allowed him to complete Poldo’s plates not always wisely, for the edifices in Gallia Narbonensis have some particularities, unknown to one of the best connoisseurs of Roman antiquity.