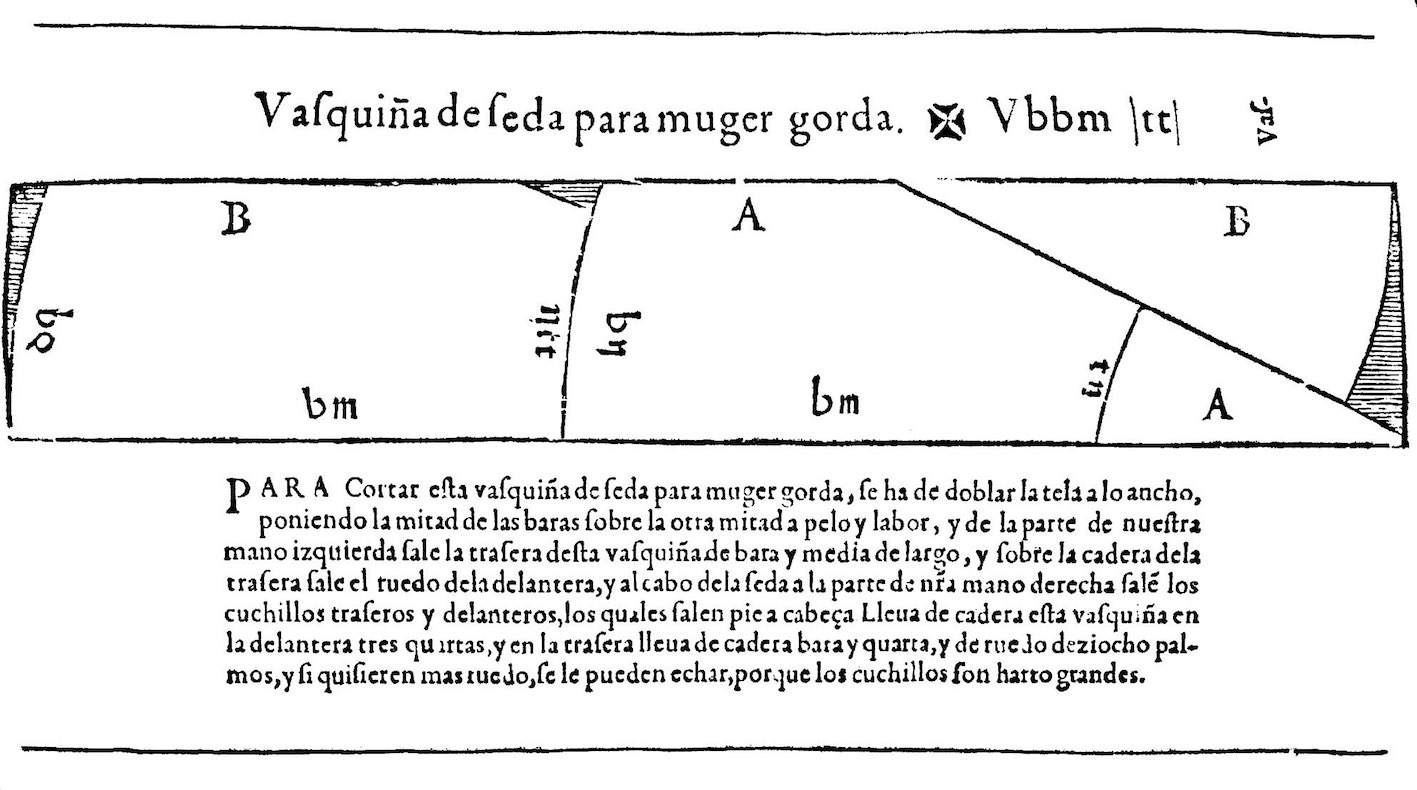

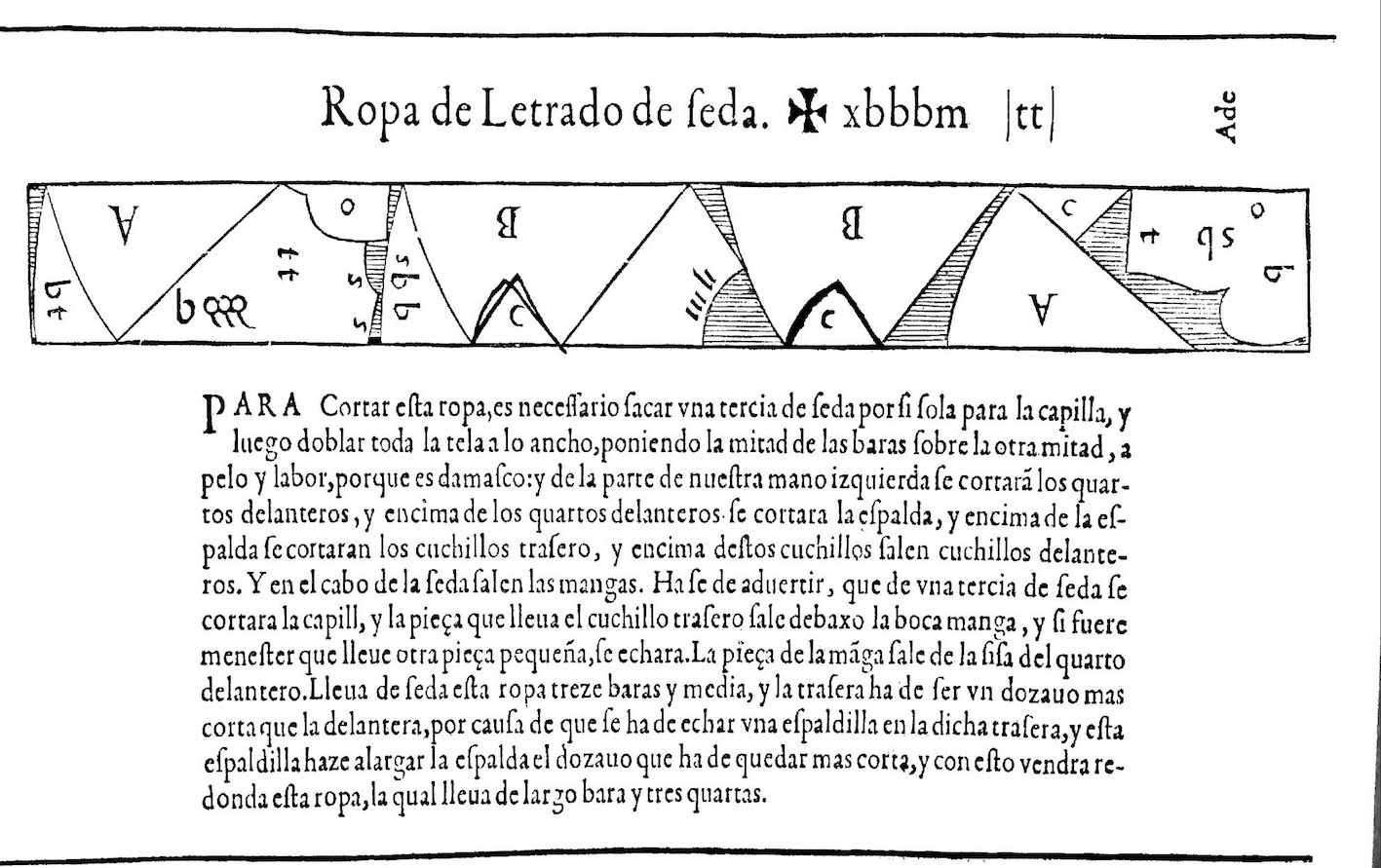

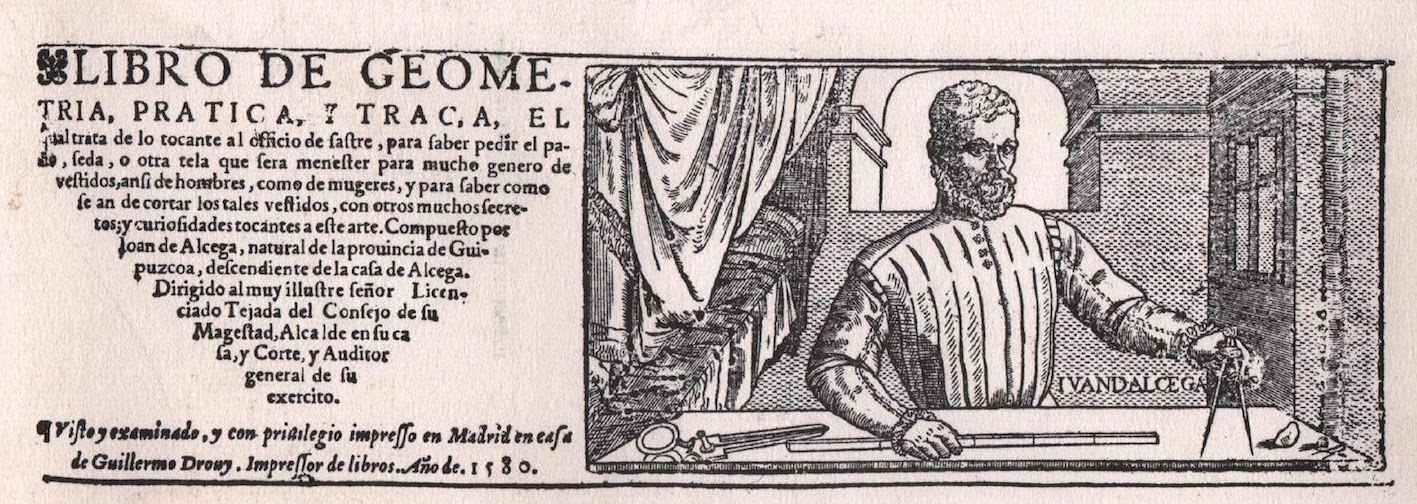

The first printed book of tailoring patterns, Libro de Geometria, Práctica y Traça (Madrid 1580, 1589) was written by master tailor Juan de Alcega under the sponsorship of the Spanish court. Borrowing the ethnographic scope of the popular costume book genre, typified by François Desprez’s Recueil de la diversité des Habits (1562) and Cesare Vecellio’s De gli habiti antichi et moderni (1590), Libro de Geometria sought to standardize customs of dress into easily reproducible, two dimensional patterns that could be cut out and sewn together into clothing (inhabitable three-dimensional shapes). The one hundred and thirty-five woodcut patterns chronicled the production of outfits appropriate for life in the various strata of Spanish society and were categorized with names that described the profession, social status, gender, material, and sometimes the physical stature of each subject – such as “Learned man’s gown of silk,” “Turkish mourning gown of cloth rash,” and “Silk kirtle for a fat woman.”

Laid out in a primarily horizontal orientation and consisting of a sequence of simple shapes outlined against a rectangular plane (representing a single length of cloth), the diagrams also included information about the optimal color and direction of the fabric’s thread. The accompanying instructions remain technical for the most part, and augment the diagrams with general directions concerning measurement, the order in which each piece should be cut out and assembled, and the conservation of material resources – a critical issue as an error in cutting velvet or brocade could cost more than its weight in silver. Although the patterns could not be utilized directly on fabric due to their reduced scale, given the overall simplicity of the outlines and the instructions keyed to each image, the implication was that a master tailor – namely, an artisan trained to think in terms of the relations between the second and third dimensions – would be able, in principle, to precisely scale the patterns up himself.

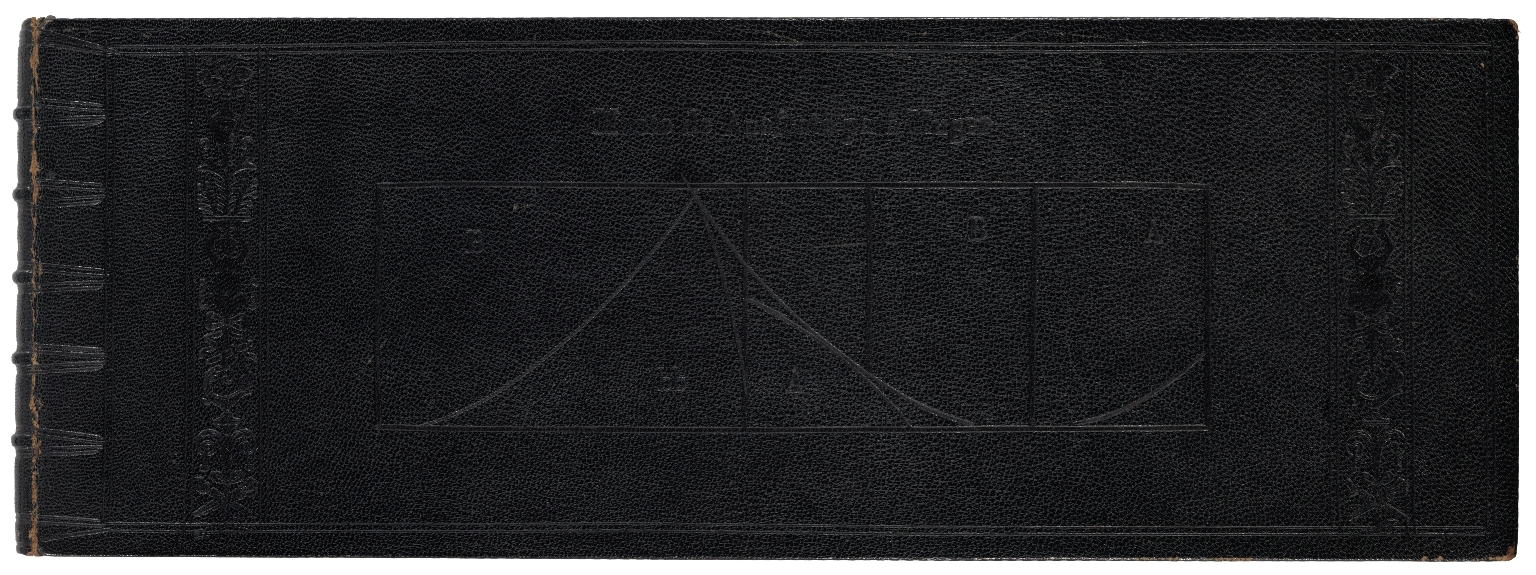

To further emphasize the criticality of material conservation, the first edition of Libro de Geometria, as well as Geometria y Traça para el Oficio de los Sastres (1588) – a volume produced by Alcega’s contemporary Diego de Freyle – were both produced as odd, oblong volumes that mimicked the proportion of the longest tailoring pattern contained within.

Here, the traditional upright folio format was eschewed in favor of utilizing the minimum amount of paper, perhaps at the expense of the ease with which the book could be handled. The perverse rigor of manipulating the exterior shape of a book to reflect its inner contents left no room for marginalia or calculations. Indeed, the relative diminishing of proportion between the spine of the book and the length of the page created a curiously fragile object, tenuously bound together, almost ephemeral in its structural improbability.

Libro de Geometria required intimate familiarity with the prevailing standards of tailoring practice, a deep knowledge of fabrics, and a sophisticated grasp of three-dimensional geometry – the information “most necessary to master the profession,” as Alcega stated in his introduction. And yet the geometrical facility and innovative assembly strategies evidenced by Alcega had very little to do with the way that geometria was taught at university, relying as general instruction did primarily upon the study of the consecutive proofs contained in Euclid’s Elements. To account for Libro de Geometria’s conceptual and aesthetic originality is perhaps to conceive of it in the context of the groundswell of applied geometry textbooks that emerged during the sixteenth century from workshops across Europe. Essential to the communication and distribution of mathematical knowledge, these image-heavy books were traded, collected, copied, and circulated, forming the printed component of an informal network of training targeted to artists, artisans, and craftsmen for whom the acquisition and application of geometrical knowledge was deemed increasingly critical.

Instruments such as a compass and ruler were essential props of mathematical activity, and it is no accident that Alcega depicts himself holding these items in the frontispiece to Libro de Geometria, a portrait intended to draw parallels with the self-conscious iconography of prominent artist-scientists, such as that of Wenzel Jamnitzer (1508-1585), world-famous goldsmith and author of a printed masterpiece on polyhedral morphology, Perspectiva corporum regularium (1568). Nevertheless, whereas Jamnitzer’s Perspectiva sought to exteriorize the relentless flux of matter, made palpable through the metamorphosis of the Platonic solids or “regular bodies” (corpora), Alcega’s ambitions cleaved in another direction, towards a definition of corpora as something divorced from the physical body and its topographic irregularities. Now substituted by a flat, fully surveyable and reproducible, man-made surface, Libro de Geometria heralded a new corporeality to which the body would be made subject, one tied to burgeoning technologies of mass production and the consequent subjectivities imbedded in the unfolding of geometrical volumes.

Fully digitised copy of ALcega’s Libro de Geometria, Práctica y Traça from the Biblioteca Nacional de España is available here.

Fully digitised copy of Freyle’s Geometria y Traça para el Oficio de los Sastres from the Folger Library is available here.