An interview with Leonard Shapiro.

Why observe 3D objects using the sense of touch?

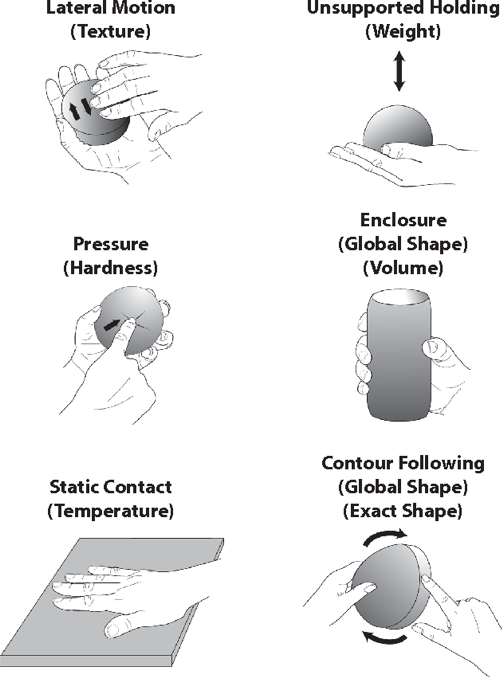

Our sense of touch is an extraordinarily powerful accumulator of tactile information about everyday three-dimensional objects. We use our sense of touch automatically and without giving it much thought, in the form of what Roberta Klatzky and Susan Ledermann refer to as ‘exploratory procedures’ (EPs), which they identified in 1987 and have researched until 2012. Yet, we seldom use our sense of touch actively in exploring and understanding objects when we wish to observe them more fully, including their 3D form. Our eyes can only inform us of so much, and by combining sight and touch, to complement what we observe with our eyes alone, we gather a great deal more information about the 3D form of an object. Neurologically, the afferent nerves from our fingers take up a relatively large area of the sensory cortex of our brain, compared to any other part of our body. This makes our sense of touch an effective sensory modality.

Two dimensional images are formed on our retina when we use our eyes to observe an object, yet when we observe that same object using our sense of touch, we are engaging directly (in a ‘hands-on’ way) with its three-dimensionality.

Haptico-visual observation and drawing (HVOD): Touch and Drawing: A method of enhanced anatomical observation and learning

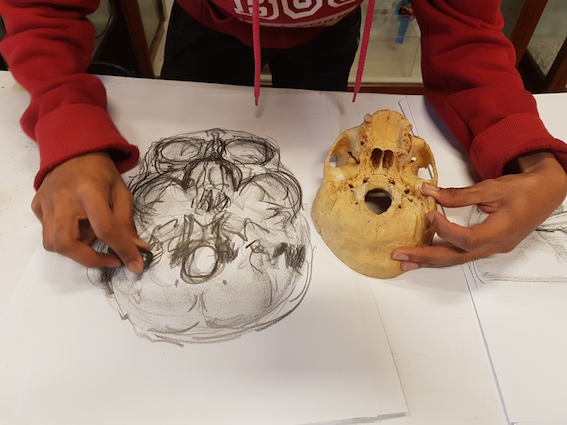

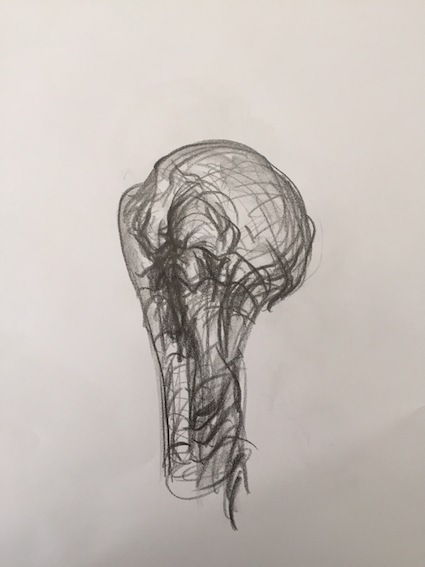

I developed the Haptico-visual observation and drawing (HVOD) method after teaching observational drawing over many years to artists and so-called ‘non’-artists alike. I realised that whenever I needed the student to observe the three-dimensionality of the object more closely and accurately, I would ask them to ‘feel the object’. The difference in their drawing was remarkable in that they reflected the observed object into 2D marks on paper which effectively re-presented the 3D object.

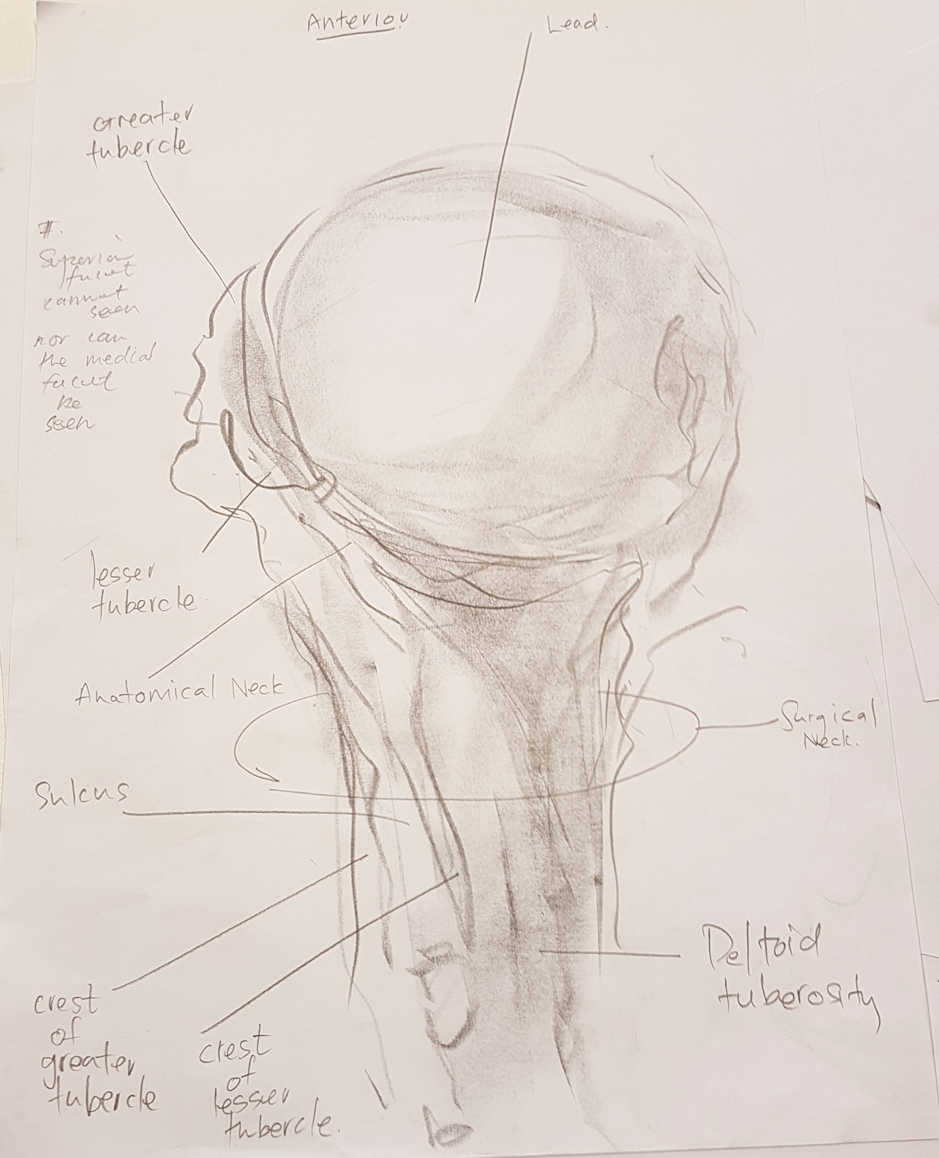

The type of drawing approach that I teach is ‘gesture drawing’ with a specific emphasis on what is known as ‘cross-contour’ drawing. The reason for this is that ‘cross-contour’ mark-making closely approximates the ‘lateral stroking’ and ‘contour following’ EPs as described by Klatzky and Lederman (see illustration).

In addition, these specific types of marks contain a ‘descriptive value’ (a semiotics value) in that each mark (singularly and in combination) describe the 3D form of the object. Marks are more fundamental, more primal than letters and words: in our evolution as humans, we made marks long before we formed letters and words. The kind of ‘descriptive marks’ that I am referring to can be seen in the portrait drawings of British artist, Frank Auerbach.

The HVOD method employs our sense of touch in combination with the simultaneous act of gesture drawing, in order to achieve the enhanced observation and memorisation of anatomical parts as a ‘mental picture’. While we observe the 3D form of an object with our ‘feeling hand’ we simultaneously make gestural marks on paper with our ‘drawing hand’ to reflect on paper what we are feeling.

‘Touch is gesture’ and ‘drawing is gesture’

When exploring an object with our fingers, we are in effect using gestures in order to acquire object knowledge – the ‘exploratory procedures’ are gestures in their own right. When drawing on paper, we make gestures as we make marks. When applying the HVOD method, we are re-presenting the EP gestures that we make with one hand, into marks on paper with the other hand. In doing so, we externalise the 3D form of the object, into marks on a 2D surface.

Students and health-care professionals who have studied an anatomical part in this way (such as a humerus, skull or heart) report being able to ‘see more’ of the object than they did before and remember and recall the object as a visual image.

On completion of an HVOD course, one medical student commented, “I still remember all the objects perfectly in my head from observing it in this way…I mean you could close your eyes and draw a humerus. Now I can see it in my mind’s eye.”

There are a number of important benefits to applying the HVOD method in the learning environment: i) closer observation and understanding of the three-dimensional form and detail of the object under investigation (such as an anatomical part). ii) cognitive memorisation of anatomical parts as a ‘mental picture’. iii) improved spatial awareness and spatial orientation within the volume of an anatomical part (for example the chambers of the heart or the space within the skull). iv) retention of anatomical knowledge over time. v) An ability to draw.

Anatomy Observation and Drawing Workshop, London, 12 August 2019

I will be running a one-day anatomy observation and drawing workshop on 12 August 2019, at The Gordon Museum of Pathology, King’s College London. To register, please see here.

In 2018, I wrote a paper How Haptics and Drawing Enhance the Learning of Anatomy with my colleagues, Steve Reid and Graham Louw. This was published in Anatomical Sciences Education (ASE) journal. Here is a link to that paper.

For more information, please visit my website: www.lateralleap.co.za.

Acknowledgements

University of Cape Town (UCT) medical students for use of their drawings. We acknowledge with gratitude the contribution of body donors to the UCT Division of Clinical Anatomy and Biological Anthropology.