Also known as the Quarto libro (Fourth book) due to where it comes in Sebastiano Serlio’s complete treaty, the work was the first to be released and was fundamental in helping to formalise and propagate the architectural language that was developed in Rome at the beginning of the Cinquecento within Bramante and Raphael’s circle.

After being initially schooled in the art of painting in his native town of Bologna, Serlio went to Rome during the 1520s to perfect his architectural culture. He achieved this by particularly spending time with Baldassare Peruzzi, to whom the treaty is greatly indebted, alongside Raphael’s students and collaborators. He subsequently moved to Venice, which really allowed him to acquire rhetorical and pedagogical skills as he benefited from his relationships with the best humanists of the town (Giulio Camillo Delminio and Aretino), alongside the artistic elite and Titian or Lorenzo Lotto with whom he rubbed shoulders. He was thus able to take on the role of professore di architettura (professor of architecture), given that he could not himself construct buildings. Alongside a series of copper boards representing the five orders that Antonio Veneziano engraved in 1528, he at that point published the initial elements of the great treaty he had already imagined – the Regole or Quarto libro (1537) and the Terzo libro (Third book) (1540). He was invited to France and in 1541 went to the court of Francis I, for whom he constructed no buildings – yet he did publish the rest of the treaty with books I and II (1545), book V (1547) and the Extraordinario libro (Extraordinary book) (1551).

At the heart of the overall form that emerges from the seven books that had been planned from the very beginning, the Regole links the first three books dedicated to apprenticeship (geometrical apprenticeship in book I, perspectives in book II and ancient culture in book III) to the last three books focusing more on creation (religious architecture in book V, civil architecture in book VI and studies of ‘accidents’ in book VII). It was therefore naturally the first book to be published, for it defines what can be seen as the most effective tool for successfully bridging the gap between the different themes at play: the modern system of architectural ‘orders’.

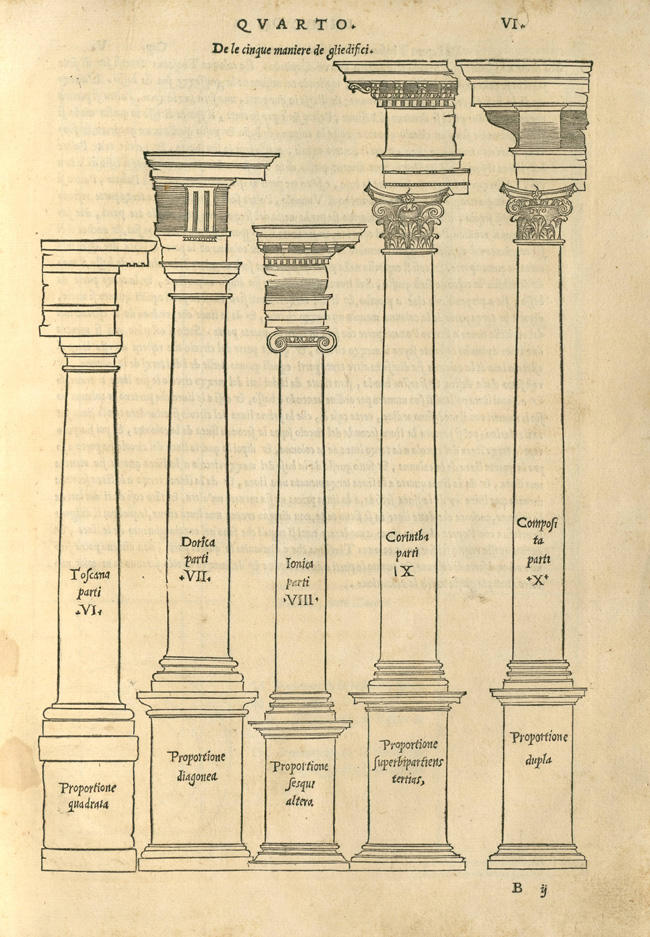

Indeed, adopting a stylistic approach, Serlio classifies all of the theoretical notions inherited from Vitruvius and the archaeological data provided by ancient ruins. The Tuscan, Doric, ionic, Corinthian and composite ‘orders’ of architecture indeed allow both for a rational analysis of the diverse nature of ancient architecture to emerge, and also for contemporary architectural creation to be provided with pertinent stylistic categories. The Regole thus puts forward particularly effective forms of grammar and rhetoric that, through the large quantity of republications and translations that were released throughout the sixteenth century and during a part of the seventeenth century, helped to convert European architecture into Vitruvian works that were adapted to the demands of modernity.

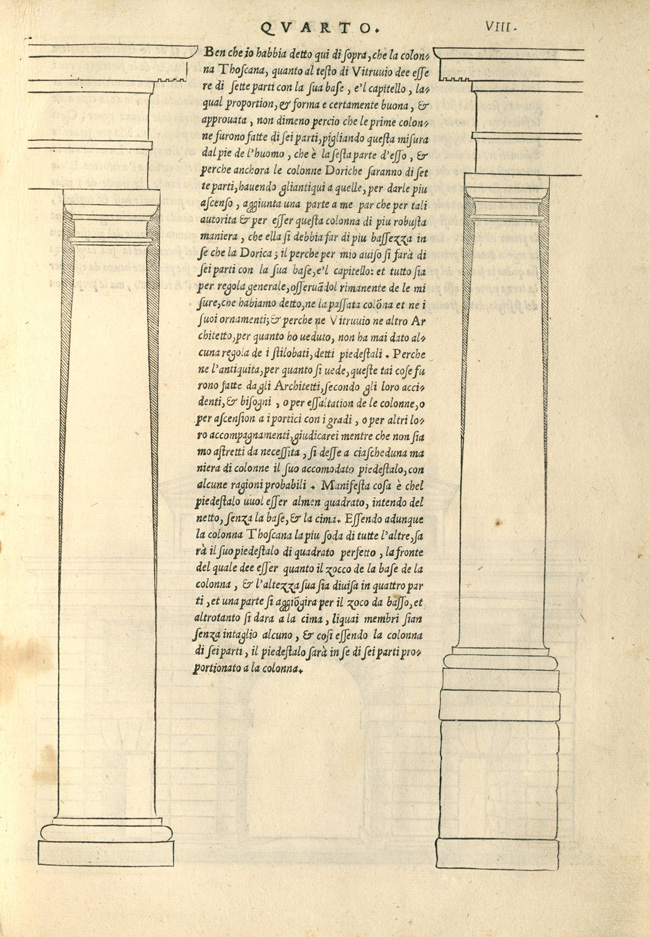

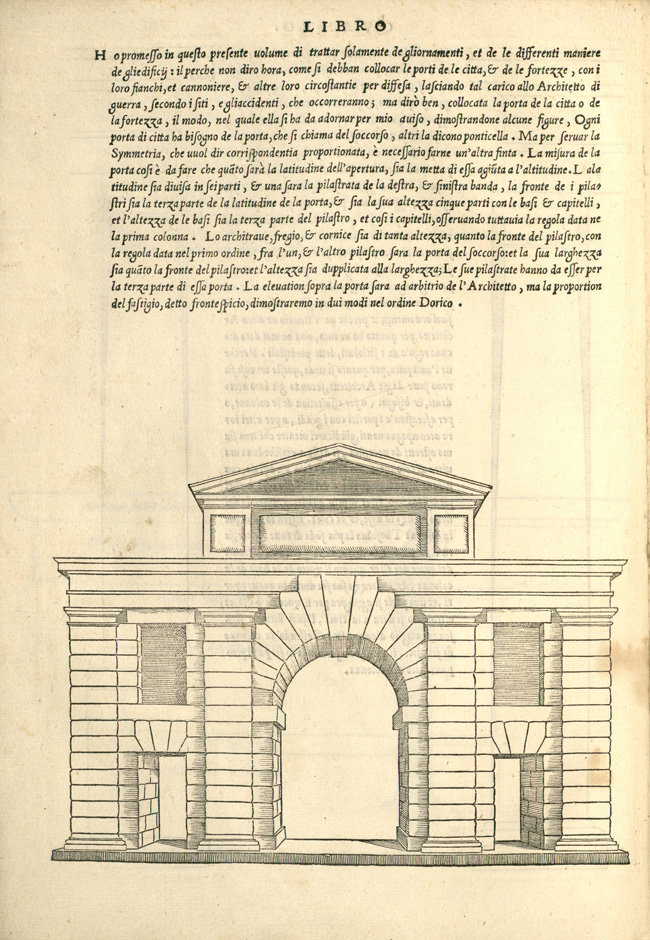

The book therefore presents the five styles one after the other; columns and entablatures are merely the most typical figures used to represent what is covered: certain examples, particularly for the Tuscan order, are included without them, yet the rustic character of their bossages is enough to make them appear in the pages devoted to the order. For each of the maniere, Serlio initially provides grammatical features (proportions, profiles and the ways in which various parts have been arranged), before recalling some ancient examples and putting forward examples of doors, frontages, chimneys and various compositions created following the style in question. Images thus play a notable didactic role here. During his youth, Serlio was himself trained in a form of painting specialising in representing decorations in perspective, which led him to becoming interested in architecture.

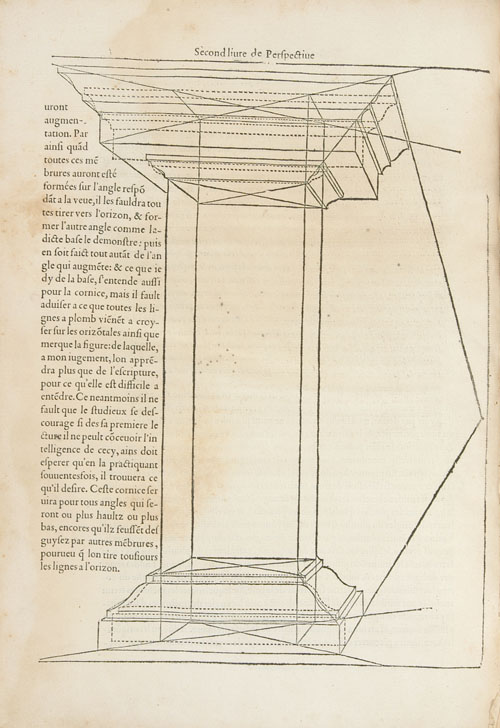

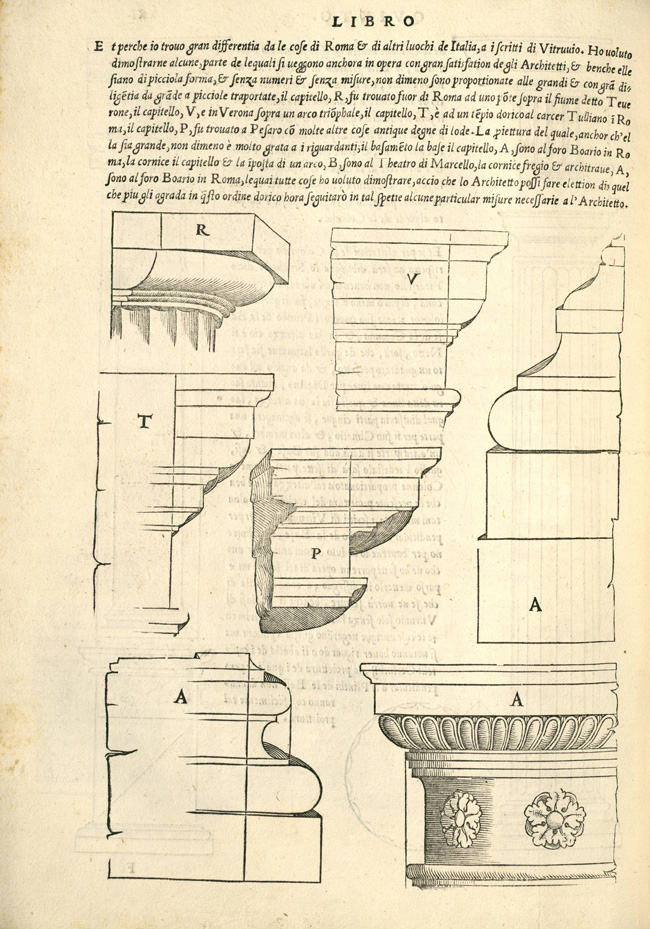

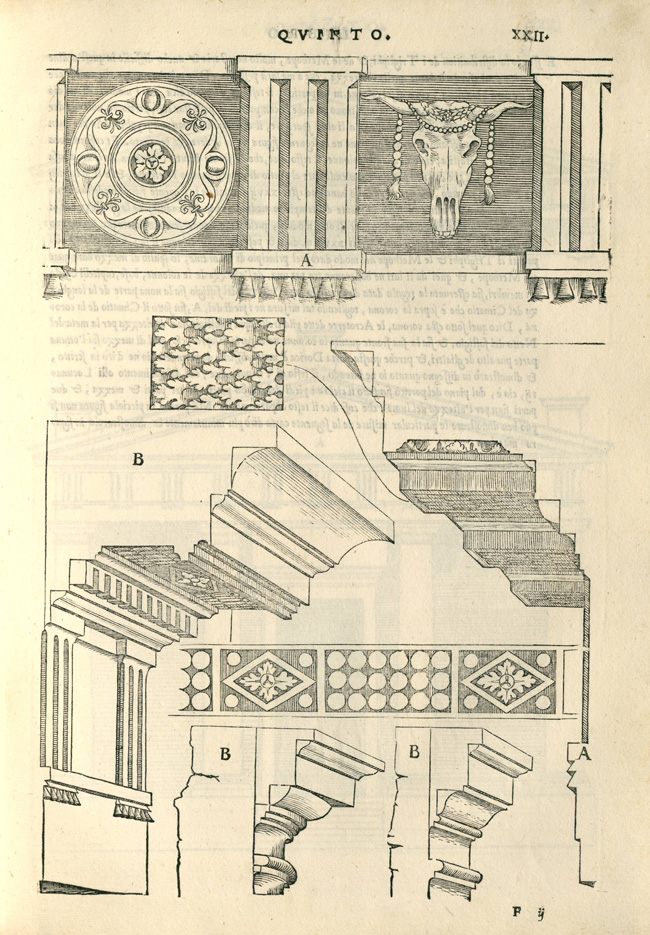

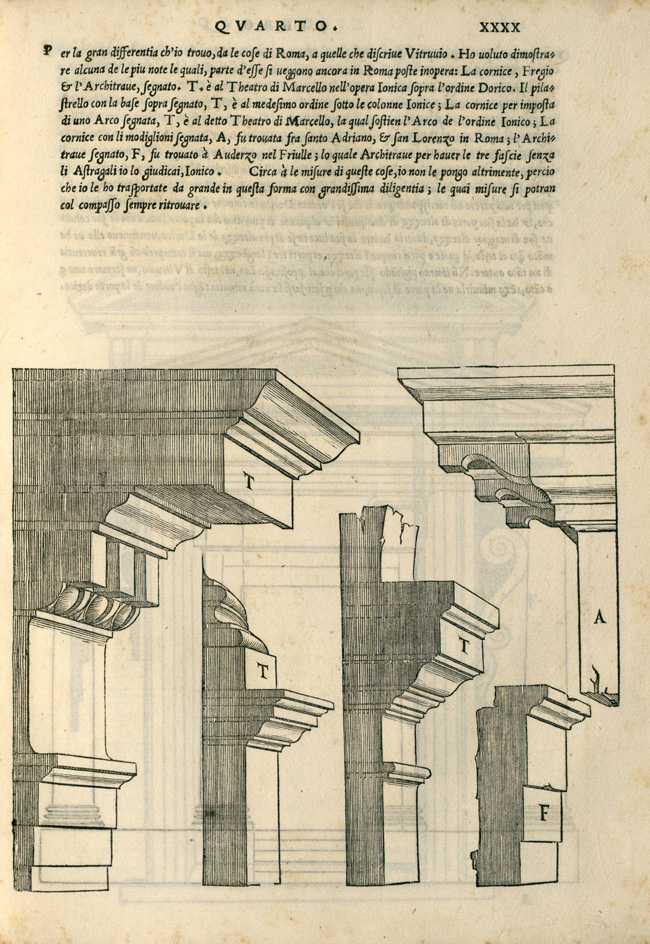

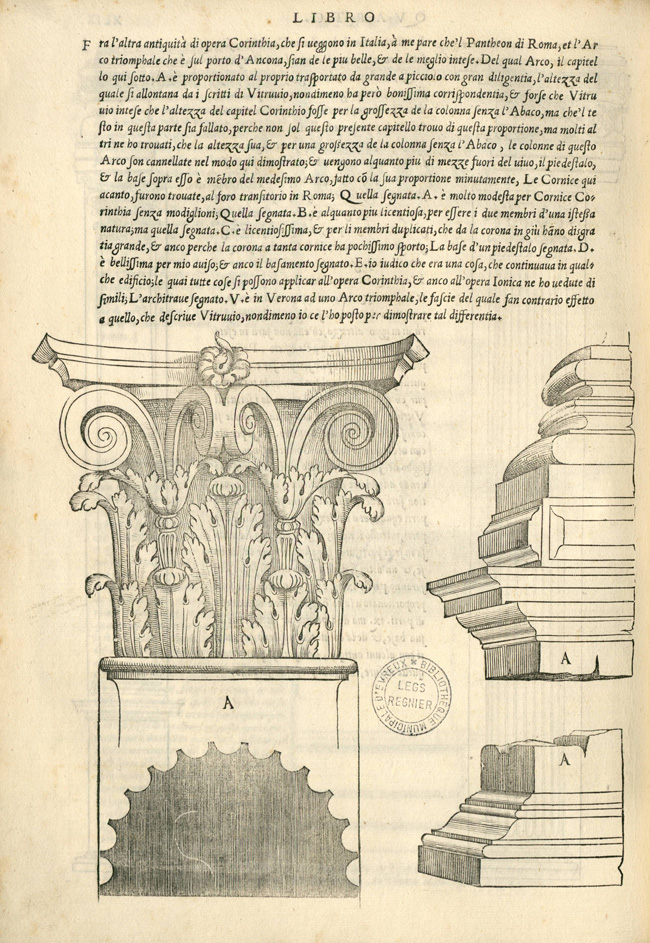

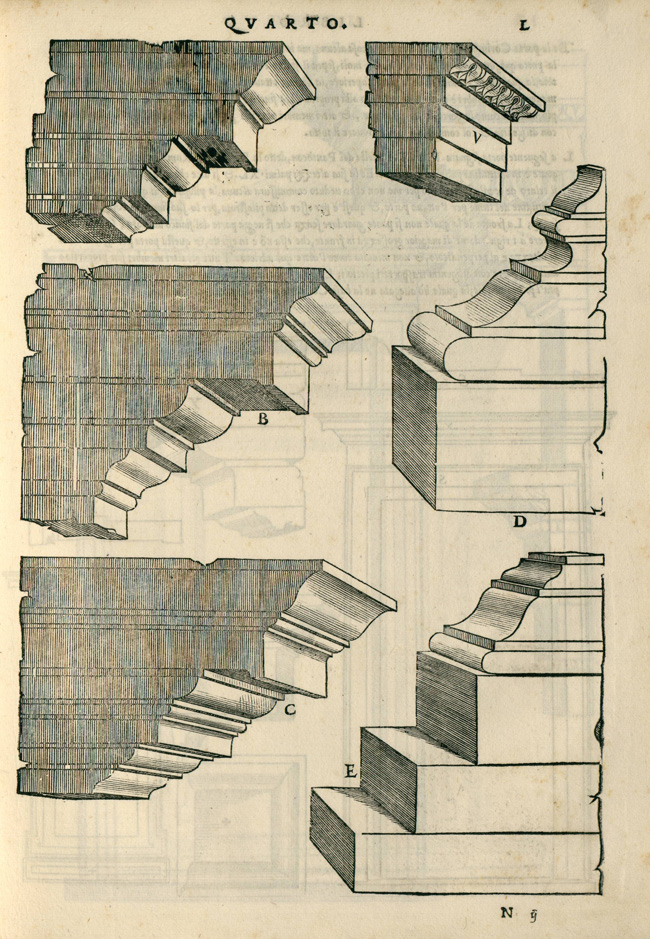

The second book of his treaty is for that matter entirely devoted to perspective views (1545). The ways in which architectural objects are represented vary according to the role they play in the book, and follow three types of representation. All of the paradigms that graphically elucidate morphological rules – full-length arrangements, base details, capitals and entablatures – are represented with pure geometrical elevation, that is to say in two dimensions without depth. These images do not require the inclusion of the third dimension – they are principally meant to be used in the creation of models, or moule (‘moulds’) in Philibert De l’Orme’s words (Premier tome, 1567, fol. 57), that is to say wooden profiles that are made to fit the desired dimensions and applied to stone so as to guide the carver.

Next, the ancient examples that are designed to enrich the reader’s culture and are only presented through some details here clearly require some amount of realism. The engravings included adopt a system inspired by the Coner Codex (London, Sir John Soane’s Museum): an orthogonal two-dimensional profile generates oblique lines that allow us to visualise the reality of the composition and the decorations of the elevation with a certain amount of perspective (fol. 21v and 22, 40, 49v and 50). In addition, hatches in the engravings create shadow effects, and thus an impression of virtual light that gives more realism to the representations.

This type of representation thus combines the objectivity of geometrical data that allows for an exact reproduction of ancient edifices, with the effectiveness of perspective views that contribute to the enrichment of visual culture. From this point of view, it is very suited to the central discourse running through the work. It was frequently used for the representations of details that were common during the Renaissance, such as those by Giuliano da Sangallo (Barberini Codex) or Michelangelo (drawings of ancient Roman buildings details in Casa Buonarroti). Finally, a note on the representations of doors, frontages or chimneys that Serlio invented and puts forward here not as models that should be reproduced as they appear in his work, but rather as examples of a form of creation that can develop an idea or theme in line with a selected style. He uses classic three-dimensional perspective views with a central vanishing point and hatching effects in the engravings that simulate a sense of depth through interacting projected shadows.

The work’s success can be measured through the rapid pace at which it was translated into other languages: in as early as 1539 a Dutch translation was released in Anvers; it was printed by the painter and publisher Pieter Coecke d’Alost who also published French and German translations of the work in 1542. Numerous authors also used Serlio’s paradigms in verbatim accounts – Guillaume Philandrier in his commentaries on Vitruvius (Rome, 1544; Paris, 1545…), Hans Blum in Germany (Quinque columnarum exacta description, Zurich, 1550; a German translation in the same year, a French translation in 1551 and numerous republications), Jean Goujon for the first French translation of Vitruvius (Architecture ou art de bien bâtir, Paris, 1547), and Jean Bullant (Reigle generale d’architecture…, Paris, 1564).

Further reading

- Mario Carpo, Metodo ed ordini nella teoria architettonica dei primi Moderni, Travaux d’Humanisme et Renaissance, 271, Geneva, Droz, 1993.

- Hubertus Günther, “Das geistige Erbe Peruzzis im vierten und dritten Buch des Sebastiano Serlio”, in J. Guillaume (ed.), Les traités d’architecture de la Renaissance, Paris, Picard, 1988, pp. 227-46.

- Hubertus Günther, ‘Serlio e gli ordini architettonici’, C. Thoenes (ed.), Sebastiano Serlio, Milan, Electa, 1989, pp. 154-68.

- Deborah Howard, ‘Sebastiano Serlio’s Venetian Copyrights’, The Burlington Magazine, 115, 1973, pp. 512-16.

- Frédérique Lemerle, ‘Genèse de la théorie des ordres : Philandrier et Serlio’, Revue de l’Art, 103, 1994, pp. 33-41.

- Frédérique Lemerle, Les Annotations de Guillaume Philandrier sur le De architectura de Vitruve, Livres I à IV, Introduction, traduction et commentaire, Paris, Picard, 2000, pp. 36-40.

- Yves Pauwels, ‘La méthode de Serlio dans le Quarto Libro’, Revue de l’Art, 119, 1998, pp. 33-42.

- Yves Pauwels, L’architecture au temps de la Pléiade, Paris, Monfort, 2002, pp. 27-58.

- Yves Pauwels, Aux marges de la règle. Essai sur les ordres d’architecture à la Renaissance, Wavre, Mardaga, 2008, pp. 21-40.

See also [Yves Pauwels’ entry] (http://architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr/Traite/Notice/B272296201_A101.asp?param=en) in the website Architectura.

Translated by Louise Ferris.