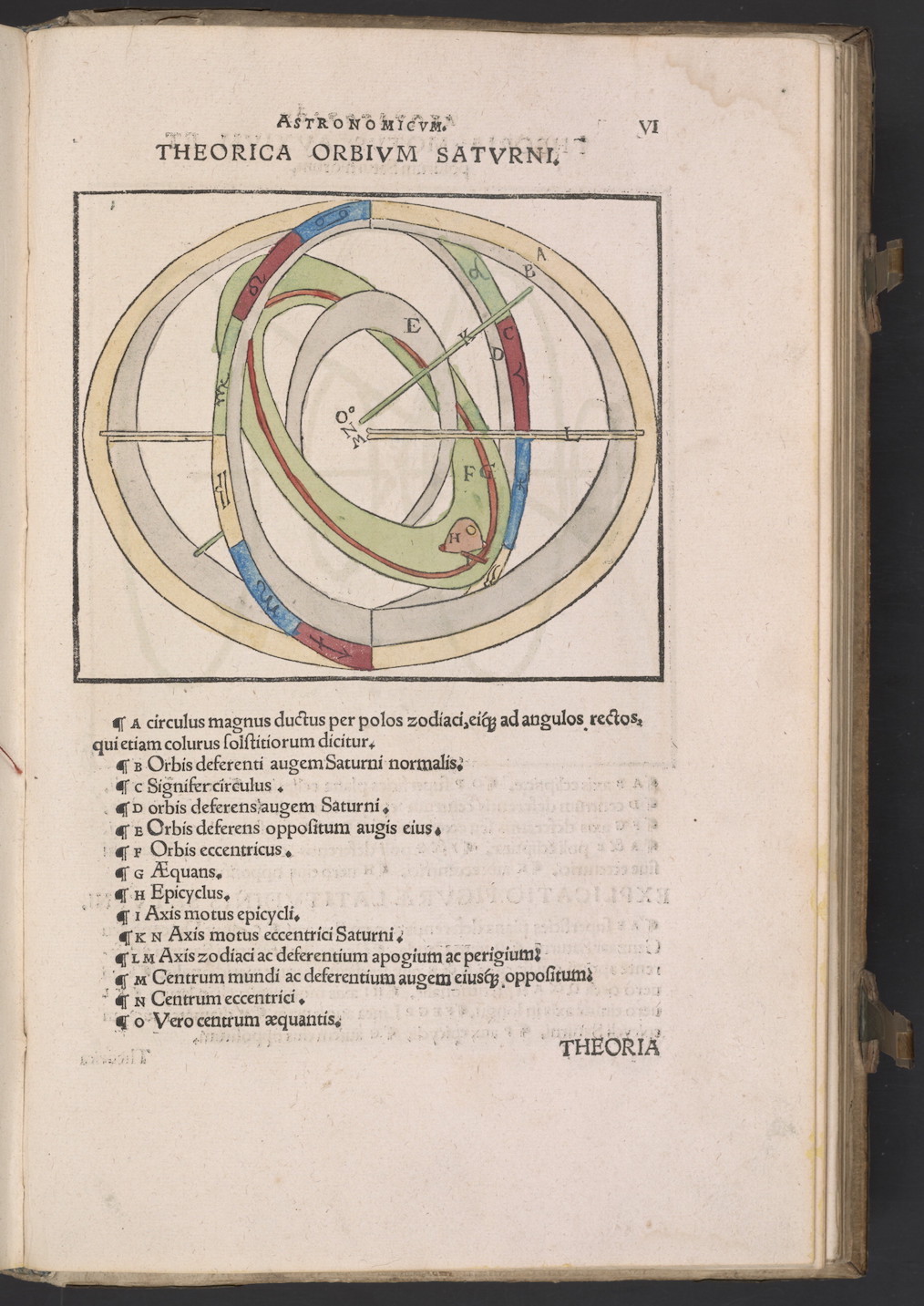

As printed astronomical treatises reached European scholars in the first half of the sixteenth century, the simple and clear depiction of the orbits and movements of the planets rose as a problem of communication; even more so after Tycho Brahe and Nicolaus Copernicus advanced new cosmographical theories contesting Ptolemaic system.

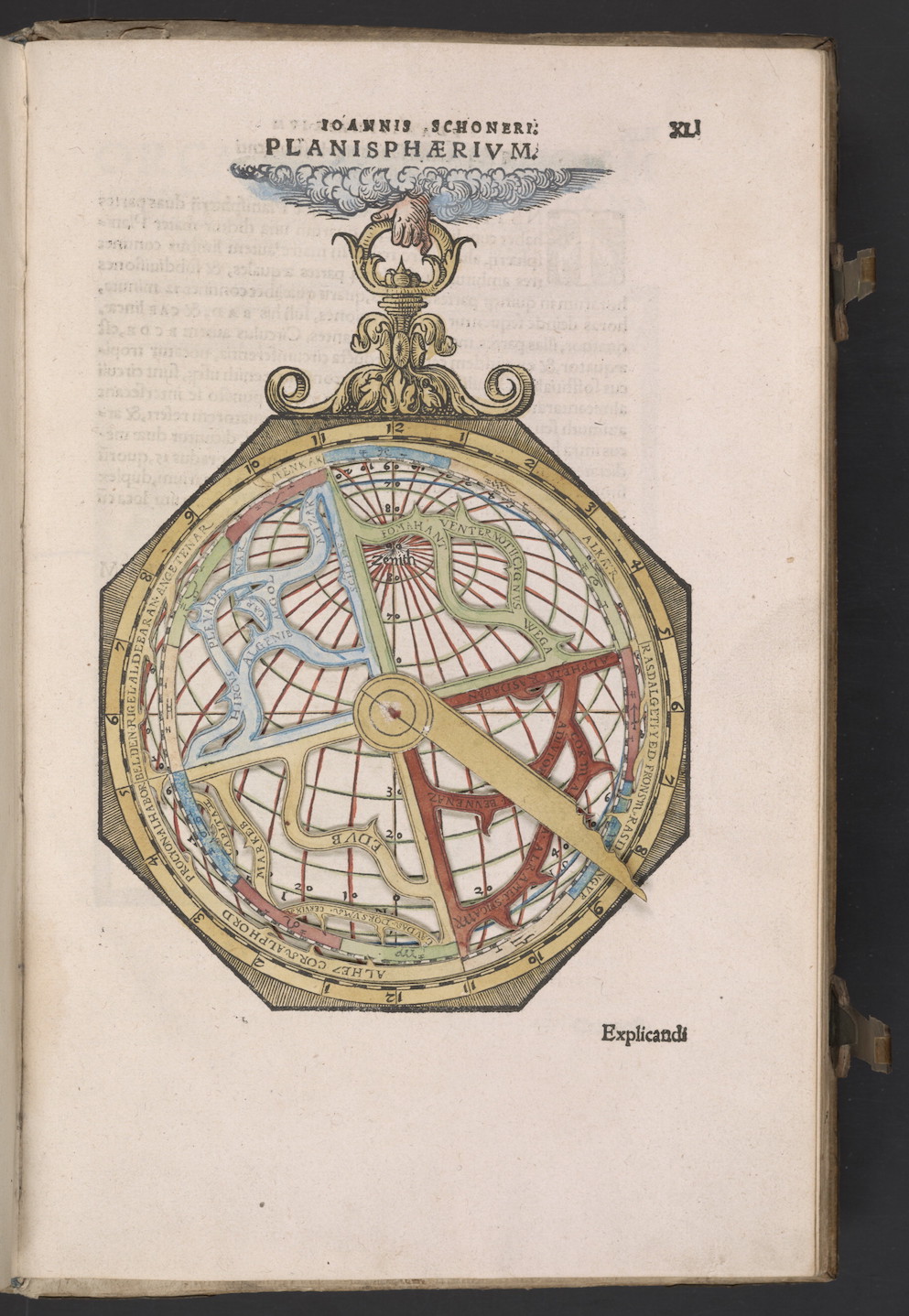

This was not only an issue of drawing but of representation technique, which Renaissance mathematicians, scholars like Johannes Schöner (1477-1547) well-versed in many scientific disciplines, experienced and developed also in map projection and drawing. Schöner, born in Karlstadt am Main and professor in Bamberg and Nürnberg from 1526, was in fact renowned for his globes, hemispheric world projections drawn in 1515, 1520, 1523 and 1533 offering some of the very first representations of the Americas.

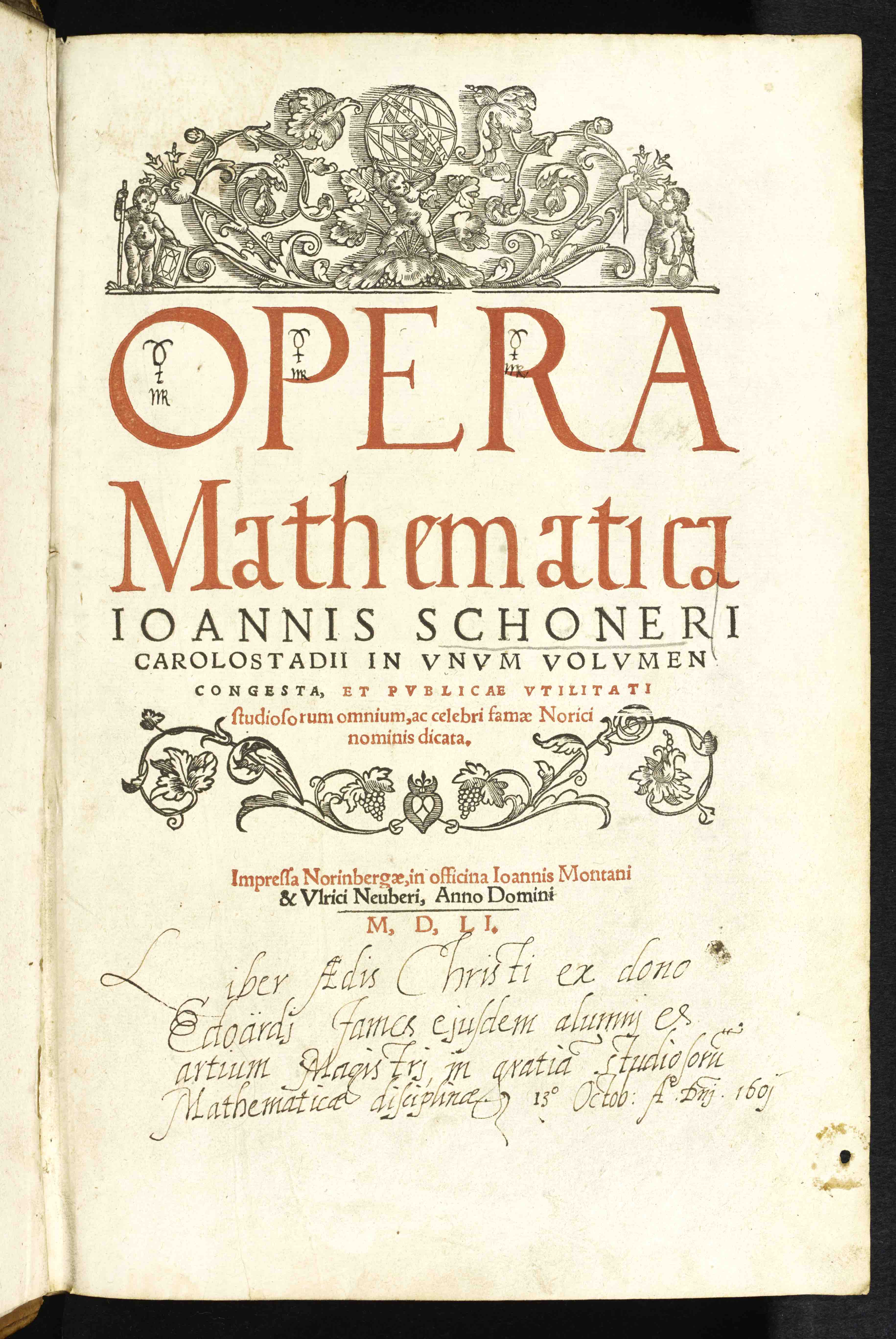

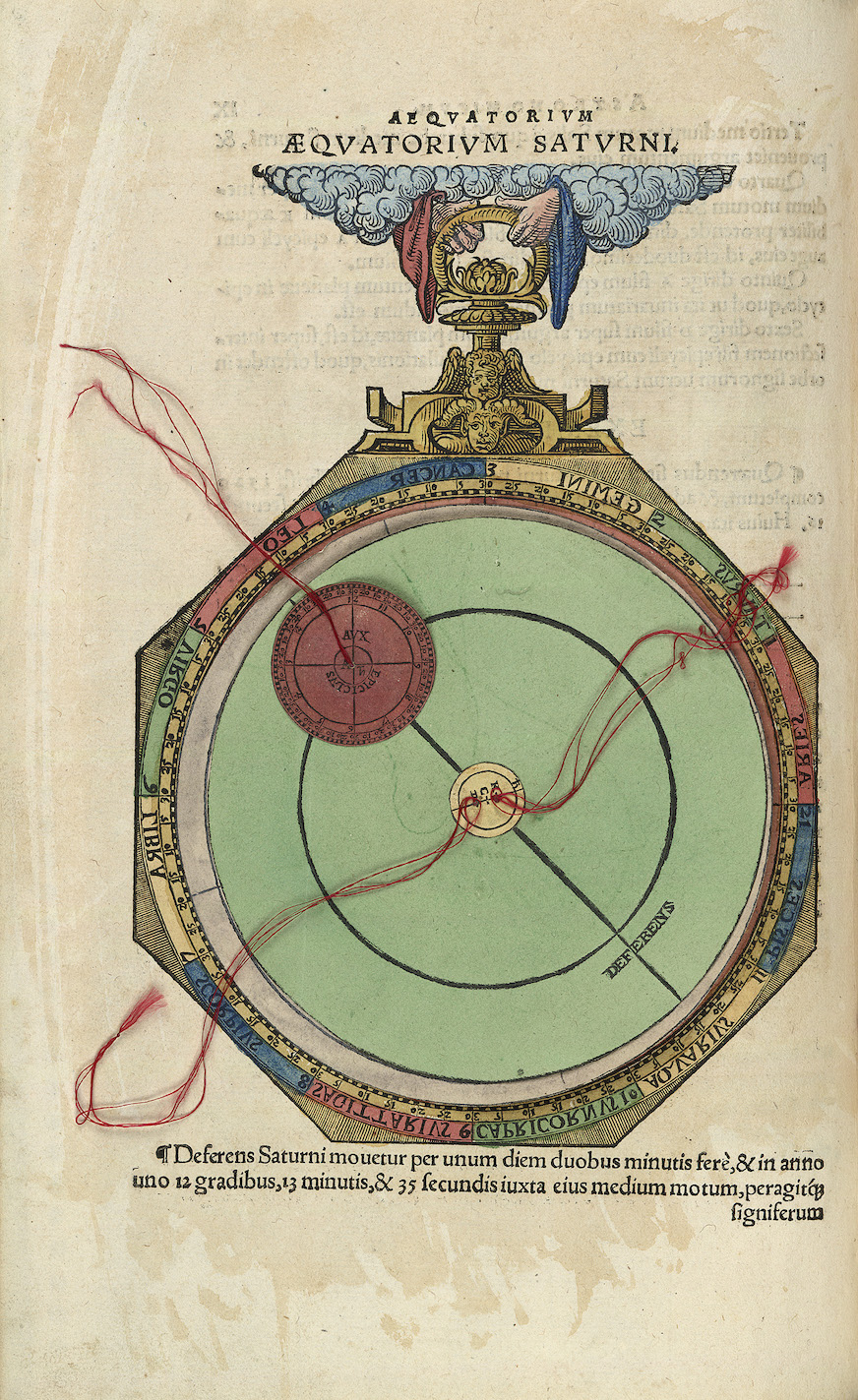

Opera Mathematica is a posthumous collection of sixteen works by Schöner edited by his son Andreas. It contains an expanded edition of the Aequatorum Astronomicum, a pioneering book in the manufacturing of volvelles published in 1521, three years before Apian’s Cosmographicus Liber.

In this re-edition Schöner improved the description of the planetary orbits, combining rotating mechanisms with perspective drawings. He designed the book in order to provide each planet with a volvelle, reproducing a bi-dimensional but moving model of a planet’s deferent and epicycle, and a corresponding three-dimensional representation as an armillary sphere. In this way, Schöner was able to incorporate a complete description of the planetary orbits, which was possible only through three-dimensional instruments such as armillary spheres – and he knew this as an instrument maker –, on the bi-dimensional surface of the book page.

Further reading

Monika Maruska, Johannes Schöner – “Homo est nescio qualis”. PhD dissertation, Universität Wien, 2008.

Norbert Holst, Mundus, Mirabilia, Mentalität: Weltbild und Quellen des Kartographen Johannes Schöner: eine Spurensuche. Scripvaz, Frankfurt/Oder 1999.

John W. Hessler, A Renaissance Globemaker’s Toolbox: Johannes Schöner and the Revolution of Modern Science, 1475-1550. Library of Congress, Washington D.C. 2013.

Fully digitised copy from the Library of Congress available here.