The architect did not exist in the twelfth century, there was only a mason who had more experience than the others on a building site. Since there was no professional training, there were no architectural drawings until the thirteenth century, when we start to see evidence of similar designs and building campaigns carried out by the same people who we can reasonably call architects. It is a surprise then to open Richard of Saint Victor’s (d. 1172) twelfth-century commentary on the Book of Ezekiel and see plans and elevations created with great skill and attention to detail.

In a vision, the prophet Ezekiel (chapters 40-48) predicted the appearance of the Israelites’ Temple complex in great detail, enumerating the measurements for courtyards, buildings and the liturgical objects. Despite this detail, following the measurements is difficult; so much so that pope Gregory the Great argued that the vision could not be understood literally and that one should read it as a spiritual allegory. After all, he pointed out, one measurement suggests that a door is wider than the wall to which it is attached! Richard disagreed, believing that proper understanding of the bible started with a literal and historical foundation.

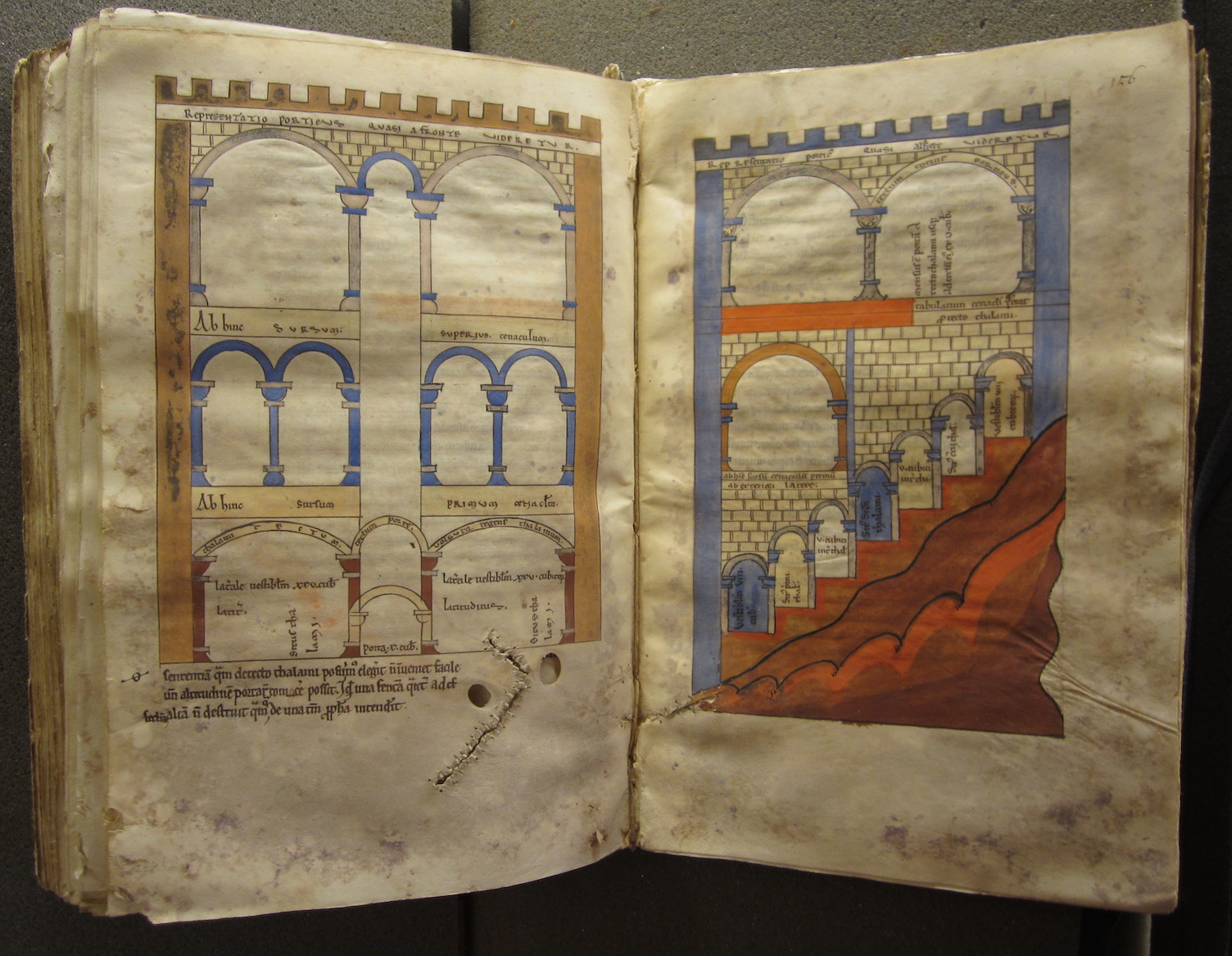

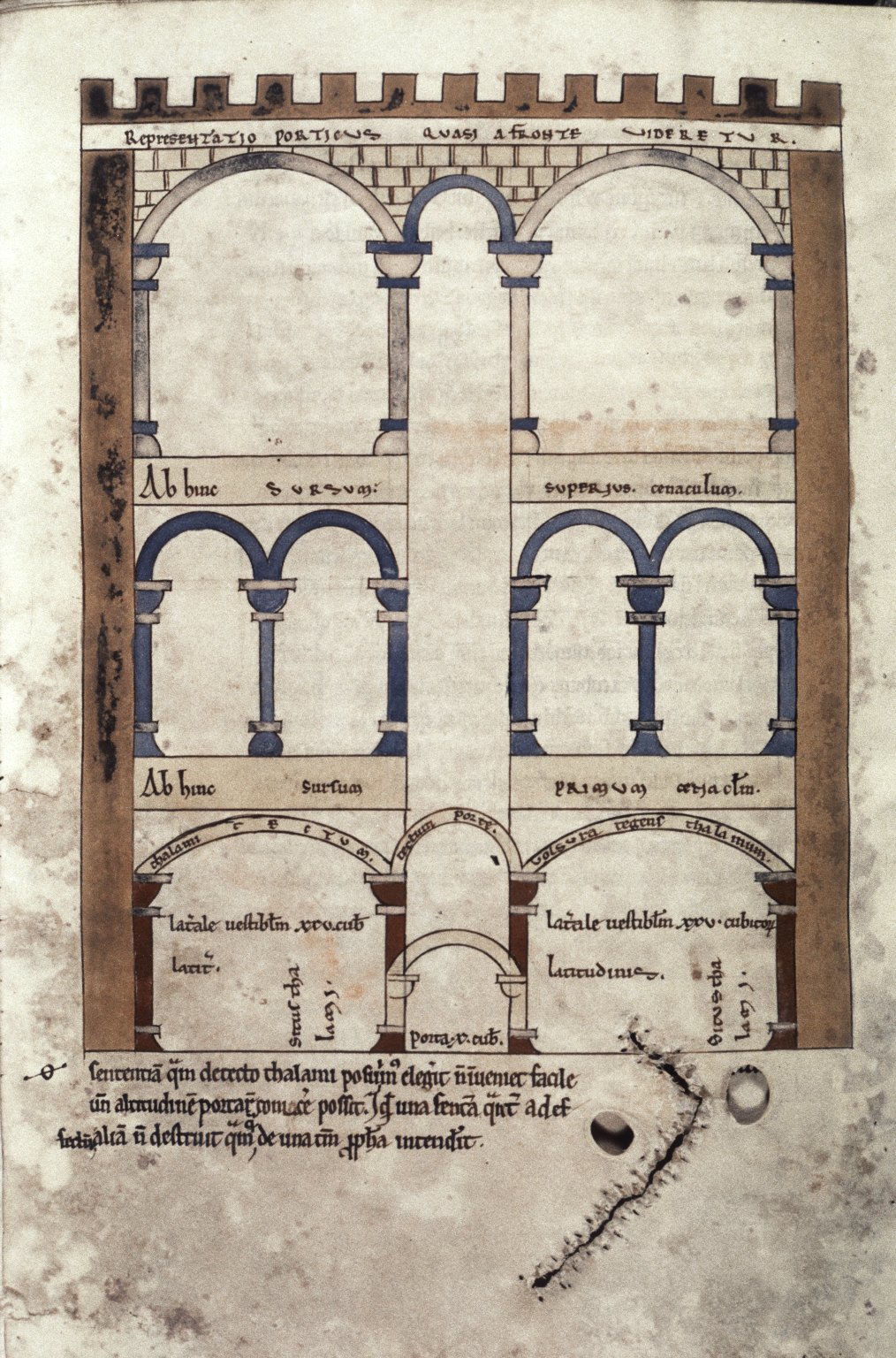

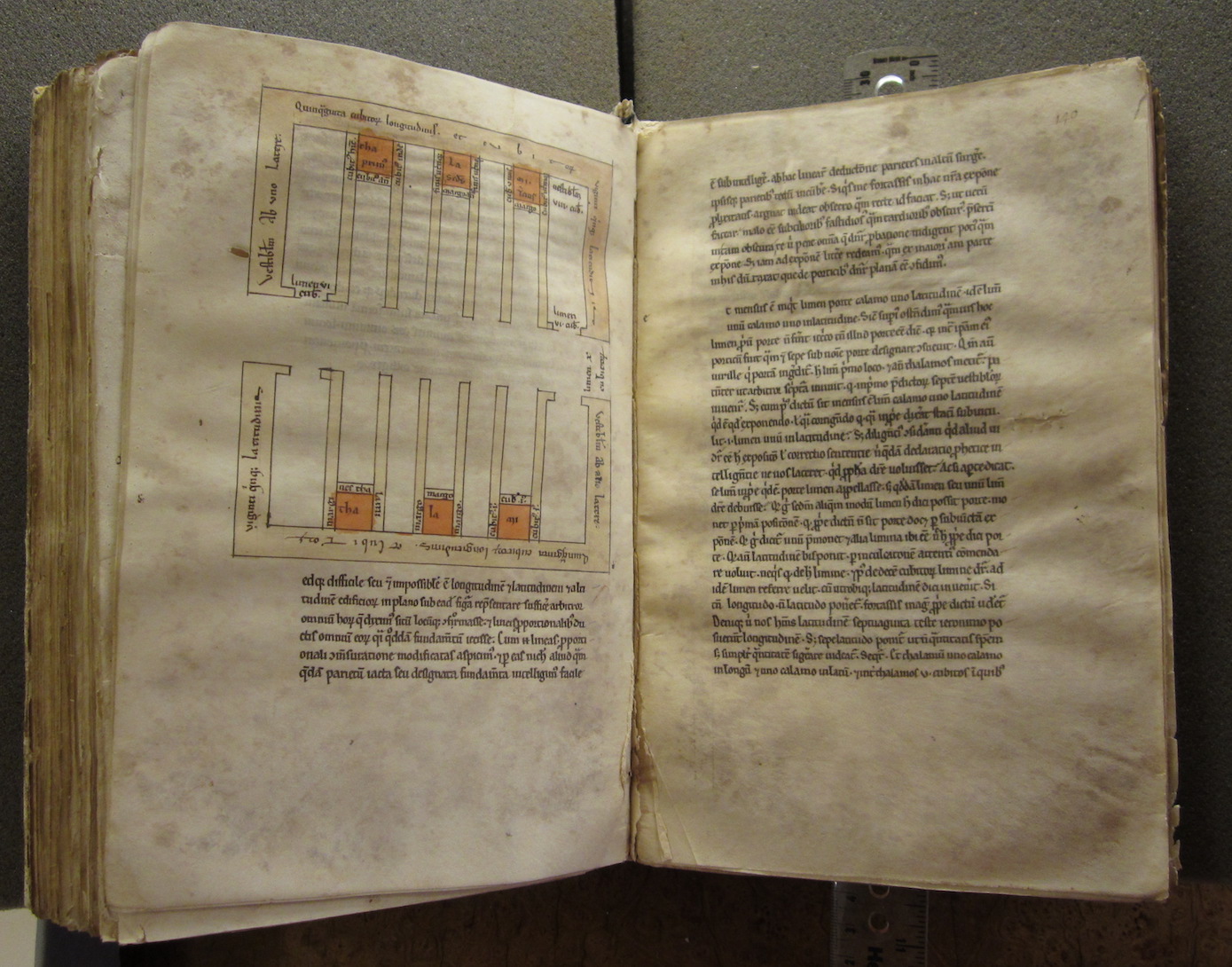

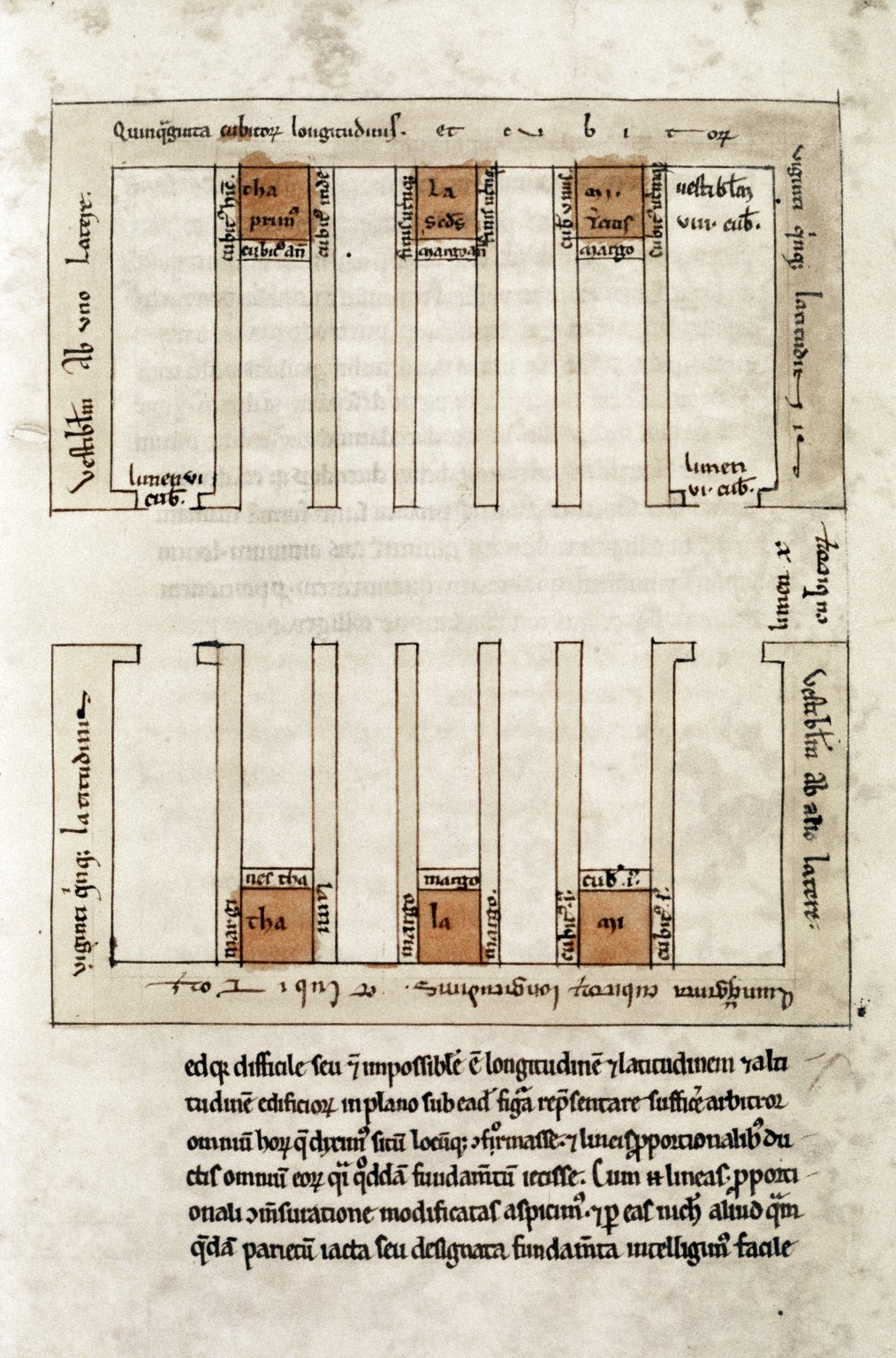

In order to convince readers of his recreation Richard provided the architectural diagrams, showing the plans and elevations of the buildings, including measurements written onto the drawings to make the relationship between the text and image explicitly clear. He included them, he writes, so that everyone ‘no matter how simple’ could understand his reconstruction. There are no drawings from the period quite like these, and Richard’s clarity of vision is startling. The combination of plan and elevation formed the core of architectural drawing up to the computer age and Richard seems to pre-empt it by half a century.

Underlining the unique approach to the problem, the work contains at least two important developments. First, Richard is the first person to use the term ‘plan’ to describe an architectural drawing. He writes that it is ‘impossible’ to show a complete three-dimensional structure ‘in plan under the same figure.’ The plan can only show the footprint of the building on the earth, with few clues about its external appearance or how it sits on a slope. Richard acknowledged the limitations of the format, and attempted to rectify the problem by including elevations of the same building, thus giving a more complete picture of the structure.

The drawing of a gatehouse from the side simultaneously illustrates the interior and exterior appearance of the building and forms Richard’s second innovation. This sectional elevation takes a similar approach to the plan, by taking a slice through the building, providing much more information to the viewer than if Richard only illustrated the outer walls. We can clearly see the arches that make up the central vestibule running through the middle of the building, and how they relate to the upper parts of the structure. There are hints that such sectional elevations were conceived earlier in the Middle Ages, but Richard is the first to provide a clear example of one that relates to an accompanying plan.

These three drawings depict the same gatehouse which Ezekiel saw standing at the northern end of the complex. The combination of plan with a frontal and lateral elevation give almost a complete picture of what Richard thought the prophet had seen. He even included flat roofs because he believed it to be the ‘custom in the land of Palestine.’

Despite these innovations there is little evidence that Richard’s work went on to influence architectural practice in the following century, when we start to see many more plans and elevations being produced. Richard’s intellectual sphere was confined to the classroom and to scriptural commentary. The work does imply, however, that sophisticated ideas of how to best represent a three-dimensional object on a two dimensional surface were forming in the twelfth century, even if we only see hints of that practice.

Further reading

Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘The Term ‘Architect’ in the Middle Ages’, Speculum 17 (1942), 549-562.

Walter Cahn, ‘Architecture and Exegesis: Richard of St.-Victor’s Ezekiel Commentary and Its Illustrations’, The Art Bulletin 76 (1994), 53-68.

Karl Kinsella, ‘Richard of Saint Victor’s Solutions to Problems of Architectural Representation in the Twelfth Century’, Architectural History 49 (2016), 3-24.

A selection of images from MS Bodley 494 is available here.

A fully digitised copy from the Bibliothèque nationale de France is available here.