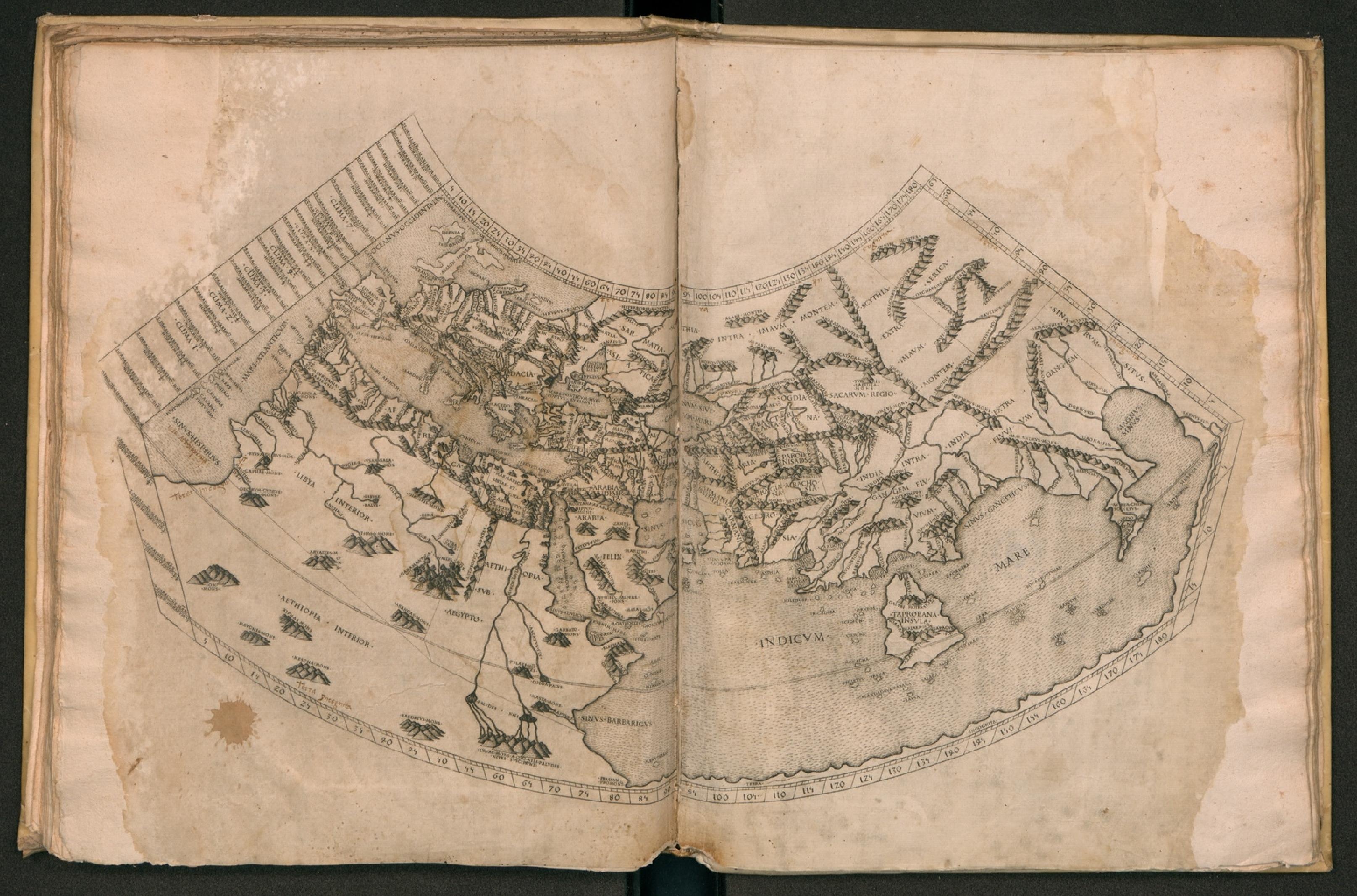

From the moment that European printers recognized the commercial potential of maps, artisans aspired to convey the earth’s three-dimensionality. One fascinating early example showcasing the skills of engravers in translating terrestrial reality into ink on paper is the edition of Ptolemy’s second-century Geography produced in Rome in 1478. Preserved in the Byzantine world, and revived earlier in the fifteenth century, the Geography set the tone for centuries of cartographic books. Yet, if the place names and coordinates of the ancient work provided a vital structure for geography, the maps inherited from Byzantium appeared flat and schematic to Renaissance eyes.

The makers of our Roman edition rose admirably to this challenge. The book’s twenty-seven engraved regional maps employ a range of techniques including subtle hatching to model a world in miniature. The printmaker’s command of light and shadow creates clusters of tiny mountains that seem to rise physically from the page. Likewise, a careful system of dots and dashes are flecked across the seas, suggesting both the movement and height of waves. These effects impart unprecedented naturalism combining the diagrammatic sensibility of a map with the emerging aesthetic of landscape.

Probably the most spectacular example of this three-dimensional thinking can be seen in the world map. Spread across two folia, it relies upon the natural form of the opened codex to present the inhabited part of the globe to readers as though seen from so great a height that the earth’s curvature appears before their eyes and at their fingertips.

Fully digitised copy from the Biblioteca Universitaria di Napoli available here.