Joseph Priestley published The History and Present State of Discoveries Relating to Vision, Light, and Colours in 1772, with the intention of making it the second volume of an ambitious history of science. Due to poor critical reception and financial difficulties, however, Priestley terminated the project after its publication. Instead of embarking on the writing of another volume, Priestley applied himself to the study of ‘airs’ and discovered oxygen – the achievement which is most widely associated with his name today.

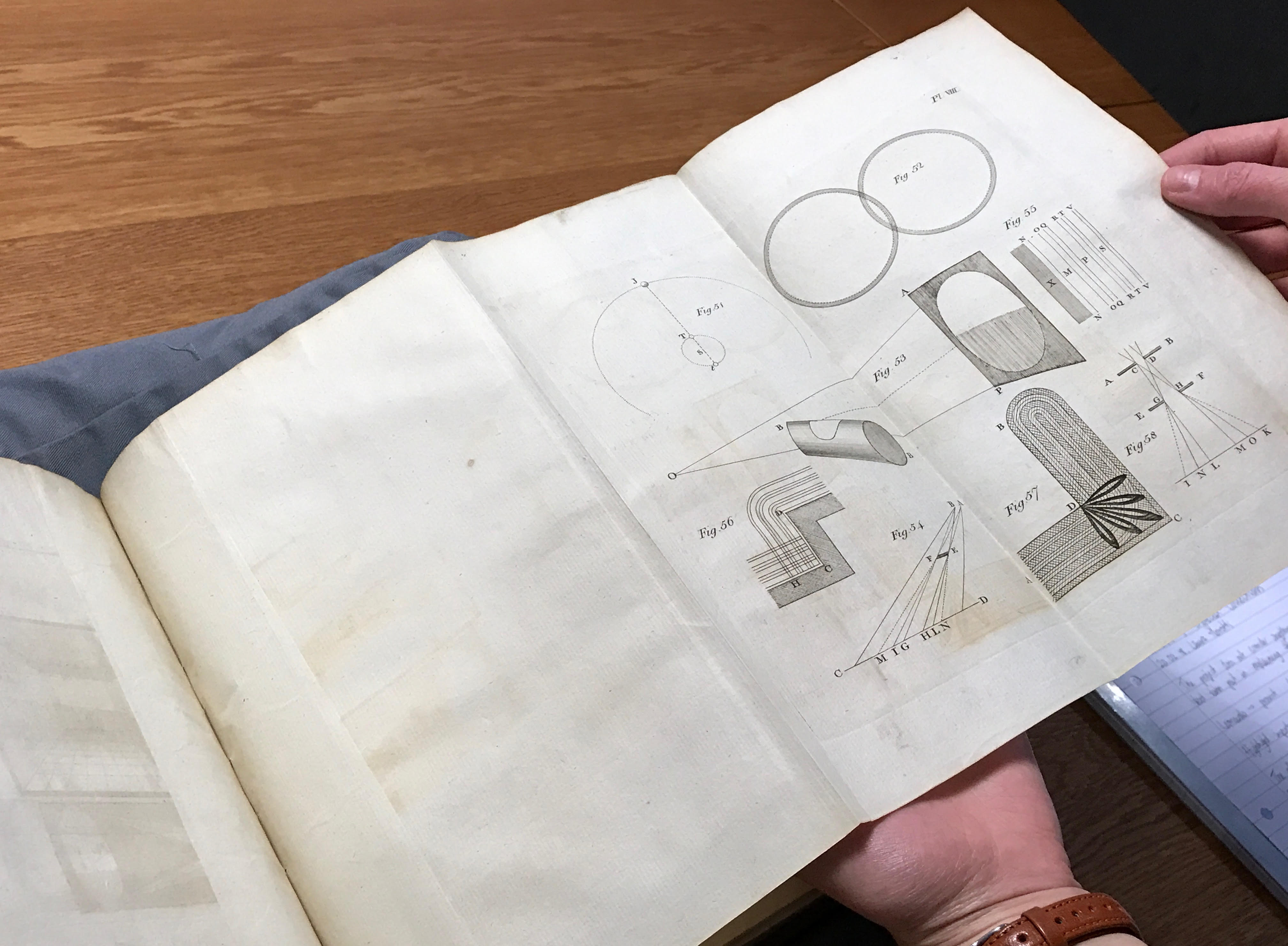

From a modern point of view, it is evident that Priestley’s engravings draw on the aestheticizing, politically charged, and interventionist tradition of scientific illustration championed by Robert Hooke in the 1660s, whilst they simultaneously assert the popular 18th-century interest to objectively and diagrammatically present the world, most famously expressed in the Encyclopédie.

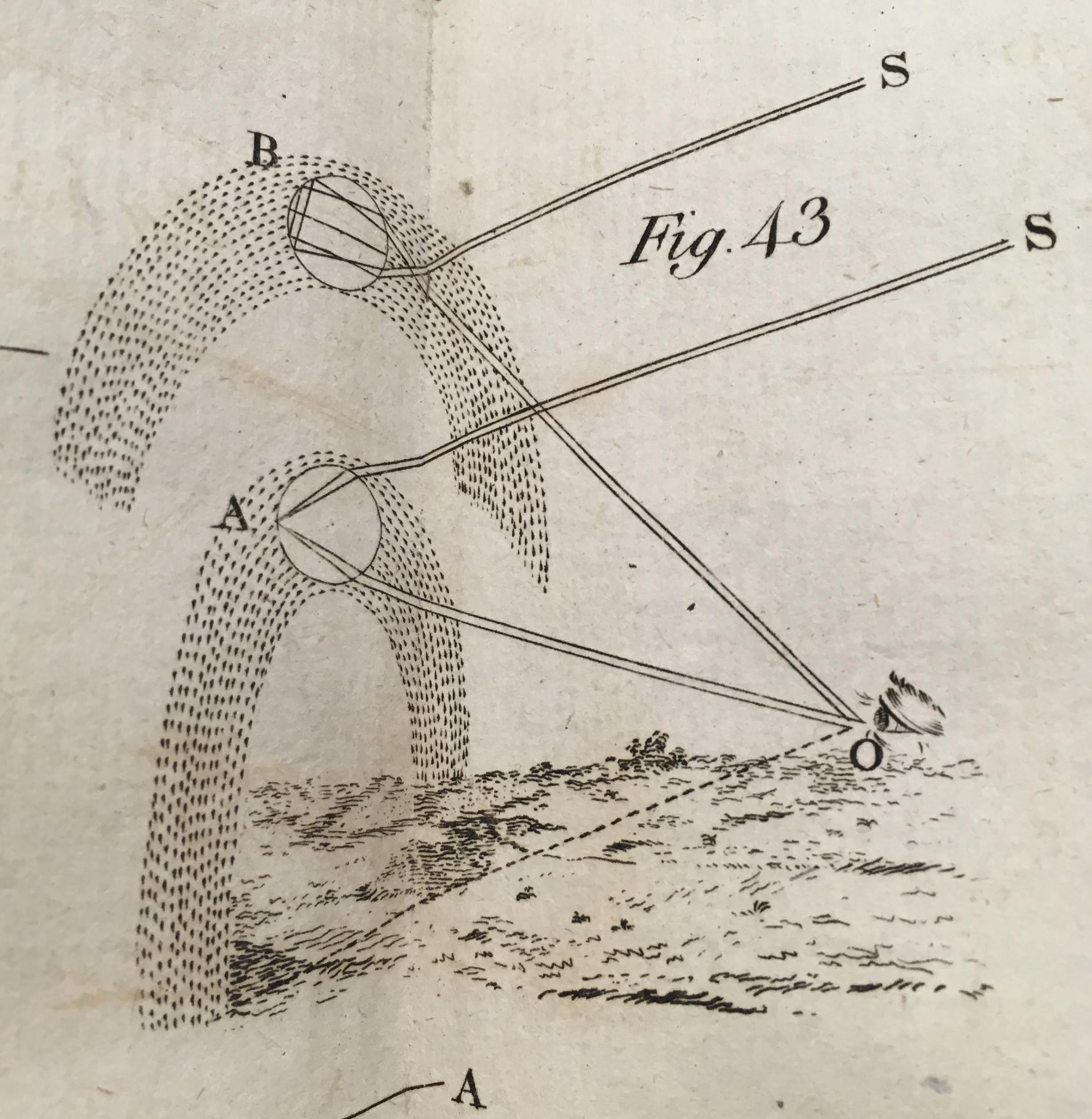

When Hooke presented his discoveries of the microscopic world in his 1665 publication Micrographia, he did so with an emphasis on the visual allure of its physical appearance. The nature of Priestley’s studies and discoveries in the field of optic phenomena necessarily required a different kind of interventionist approach, which is reflected in the way his illustrations combine geometrical figures, highlighted trajectories of light, and letters, with pictorial renditions of everyday objects, landscapes, human figures, and disembodied eyes.

The disembodied eye is a frequent feature of the edition’s illustrations, anchoring the various phenomena in the sensory experience the book revolves around. Priestley’s emphasis on the direct observation of phenomena alongside their underlying principles is evident in both the illustrations and their corresponding pieces of text. With reference to Aristotle’s De Anima, Priestley stresses that the only way we can meaningfully describe phenomena is based on how we perceive them with our senses. Consequently, the disembodied eye takes on a scientific quality as the mediator between physical phenomenon and intellectual understanding.

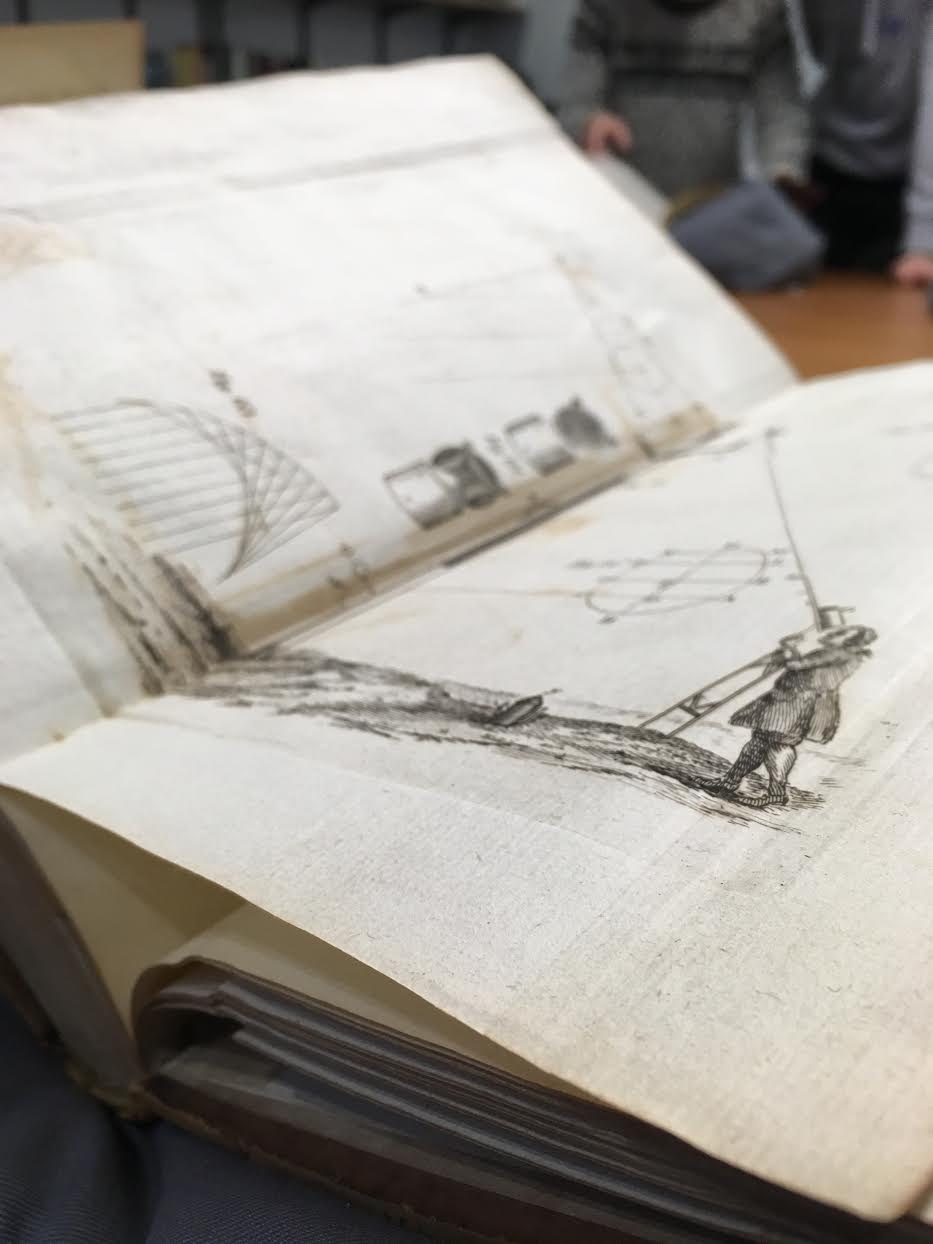

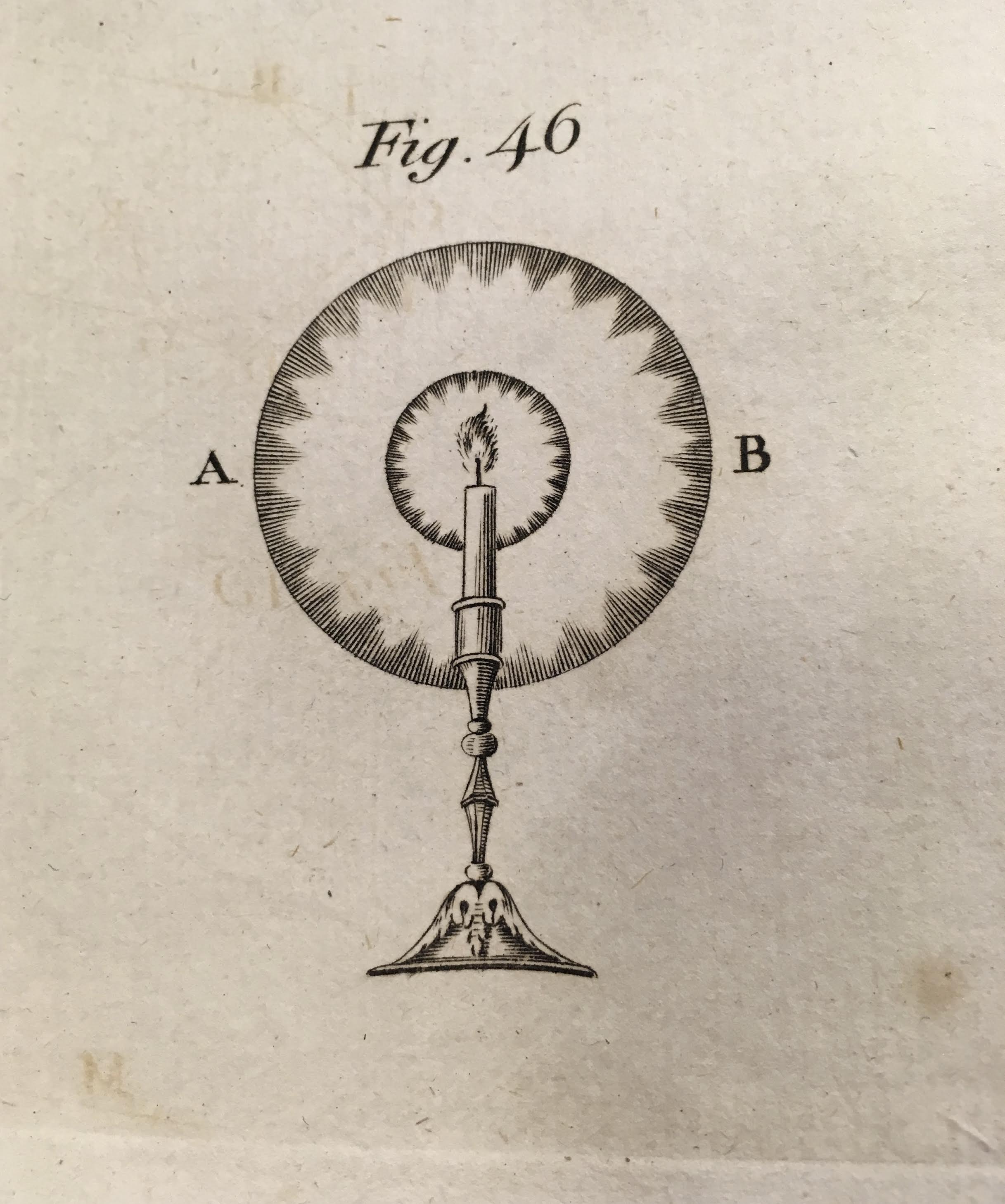

For a modern readership, however, it is important to bear in mind that Priestley was not a professional scientist in the contemporary sense of the term; although Priestley’s career corresponded with the emerging identity of the ‘man of science’, science was not yet firmly established as a professional field. Priestley used the freedom this entailed to make statements beyond the field of optics in his illustrations. Especially in his representations of people and objects, he makes clear attempts to elevate his own status. For example, the fashionably dressed man who demonstrates the use of Huygens’ telescope, and the richly ornamented candleholders used as props suggest that the realm of science – although it entails physical labour – is nevertheless fit for gentlemen.

In recent scholarship, there is growing recognition that Priestley’s religious focus and scientific beliefs are intimately linked, and cannot be studied separately. Priestley expressed the responsibility of the scientist to materialize powers of the creator, to draw ‘the lightning from the clouds into a private room,’ evidently leading to his desire to chart histories of scientific and visual phenomena. Throughout the text, Priestley emphasizes the dual role of the individual to bring forth higher powers onto the page, and to advance enlightenment to wider participation and learning.

Priestley’s analytic, diagrammatic illustrations, notably his highlighted trajectories of light, clearly guide the eye through the presented compositions and processes, engaging viewers in instruction. Through such illustrations, he expresses his simultaneous commitment to rationality and revelation, and the individual’s role of rooting optical phenomena in comprehensible, visual terms as to manifest higher powers.

Priestley’s theological and political interests profoundly informed his work, and necessitated a collaboration between textual and visual media in the presentation of his knowledge and ideas. Within the edition, Priestley’s illustrations play a complementary part – they do not command centre stage like the illustrations of 19th-century atlases, but provide the reader with visual experiences that contribute to and draw upon the content of the author’s writing.

Thea Moe Bjøranger and Sophie Levine

Fully digitised copy from the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science is available here.