Guillaume Philandrier had accompanied his employer Georges d’Armagnac throughout his periods as ambassador to Venice (1536-1539) then to Rome (1540-1545). In Venice Philandrier had been initiated in architecture by Sebastiano Serlio in person and was aware of the most modern theory, while reading the De architectura together with d’Armagnac, himself widely read. It was probably at this time that the philologist, already the author of a brief commentary on Quintilian in the form of annotations, planned the project of commenting on the antique treatise. Thus in Rome in 1544 he published at the printing shop of Giovanni Andrea Dossena his Annotationes on the De architectura by Vitruvius, the fruit of his Italian experience. The Digression on the five orders (Quoniam in rei ædificatoriæ ornamentis, etc….) that he inserted before the notes of chapter 3 of book III is the synthesis of previous theoreticians (Alberti and Serlio) and the fruit of his own reflection on the antique vestiges he studied (Fig. 1).

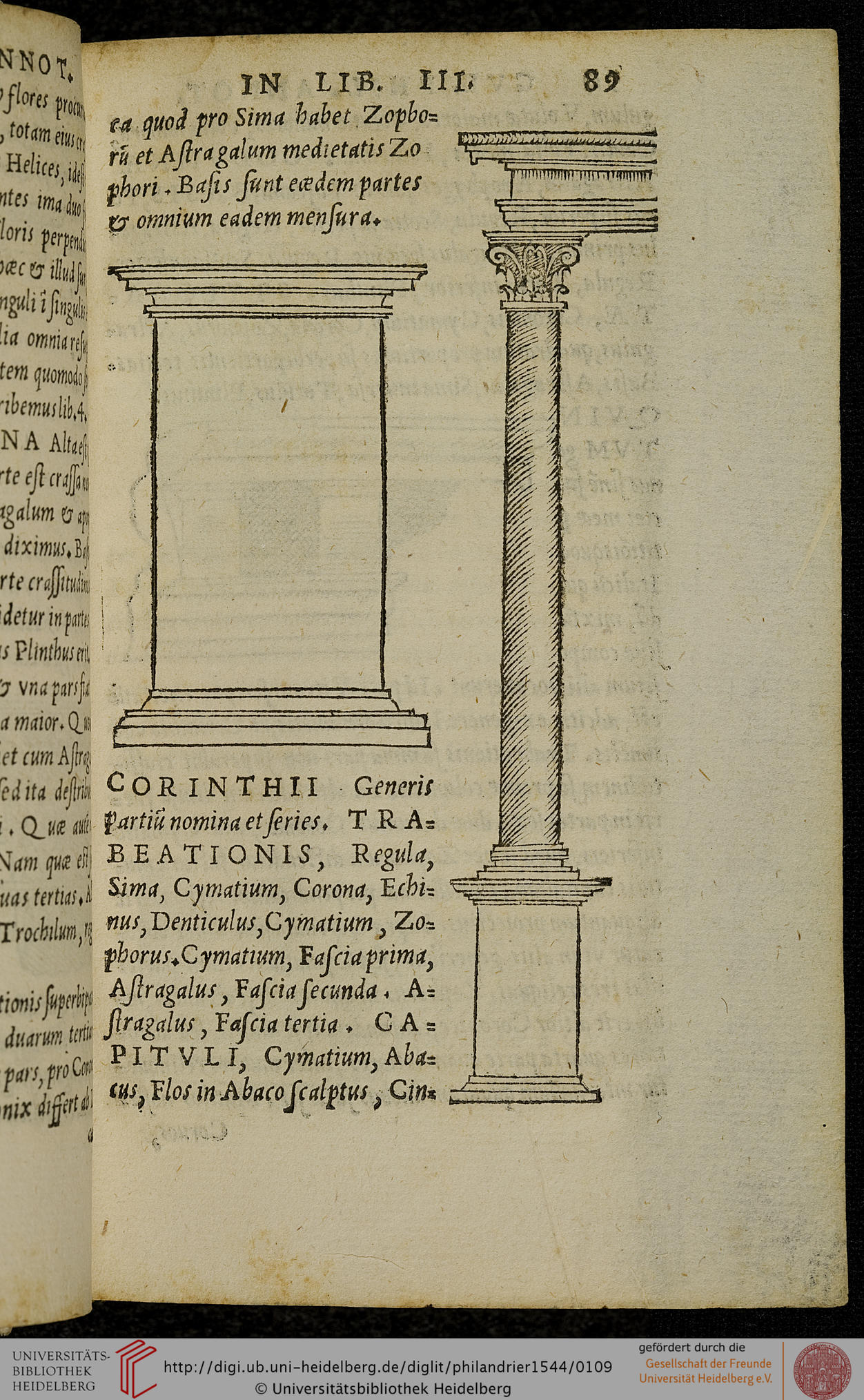

Although he kept the principal of the five orders, in comparison with Serlio it constitutes a major theoretical step forward without which it is hardly possible to understand the Regola by Vignola and in a general way the trattatistica of the second half of the Cinquecento. Philandrier went beyond Serlio’s purely lexical presentation by integrating it in a much more normative morphological discourse. Like each Latin declension, each one of the five orders is endowed with precise forms, in this case a succession of specific horizontal and vertical elements, whose proportions and mouldings are determined in a definitive way and whose use or the syntax, is strictly regulated. Therefore one single model corresponds to each order (Fig. 2).

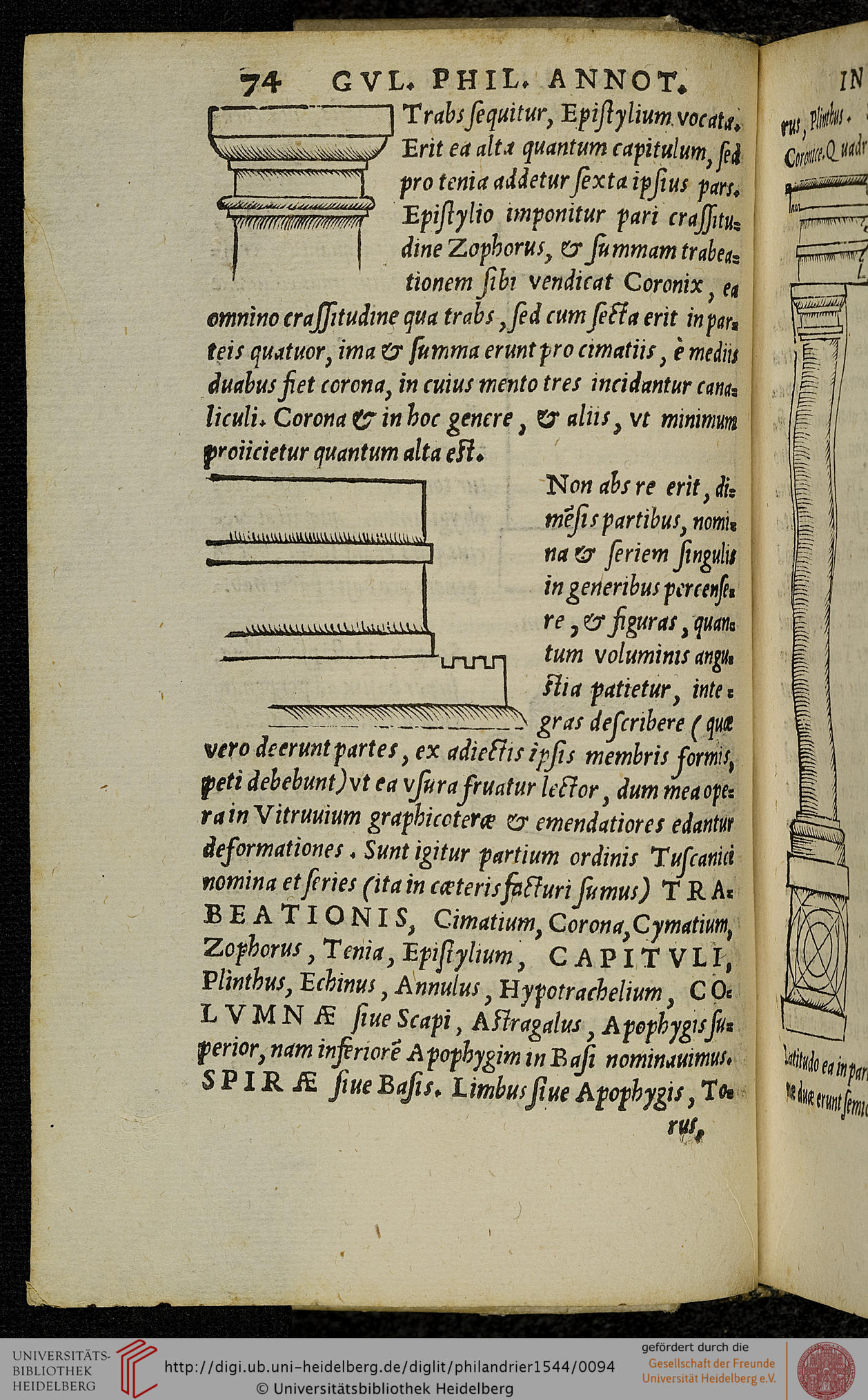

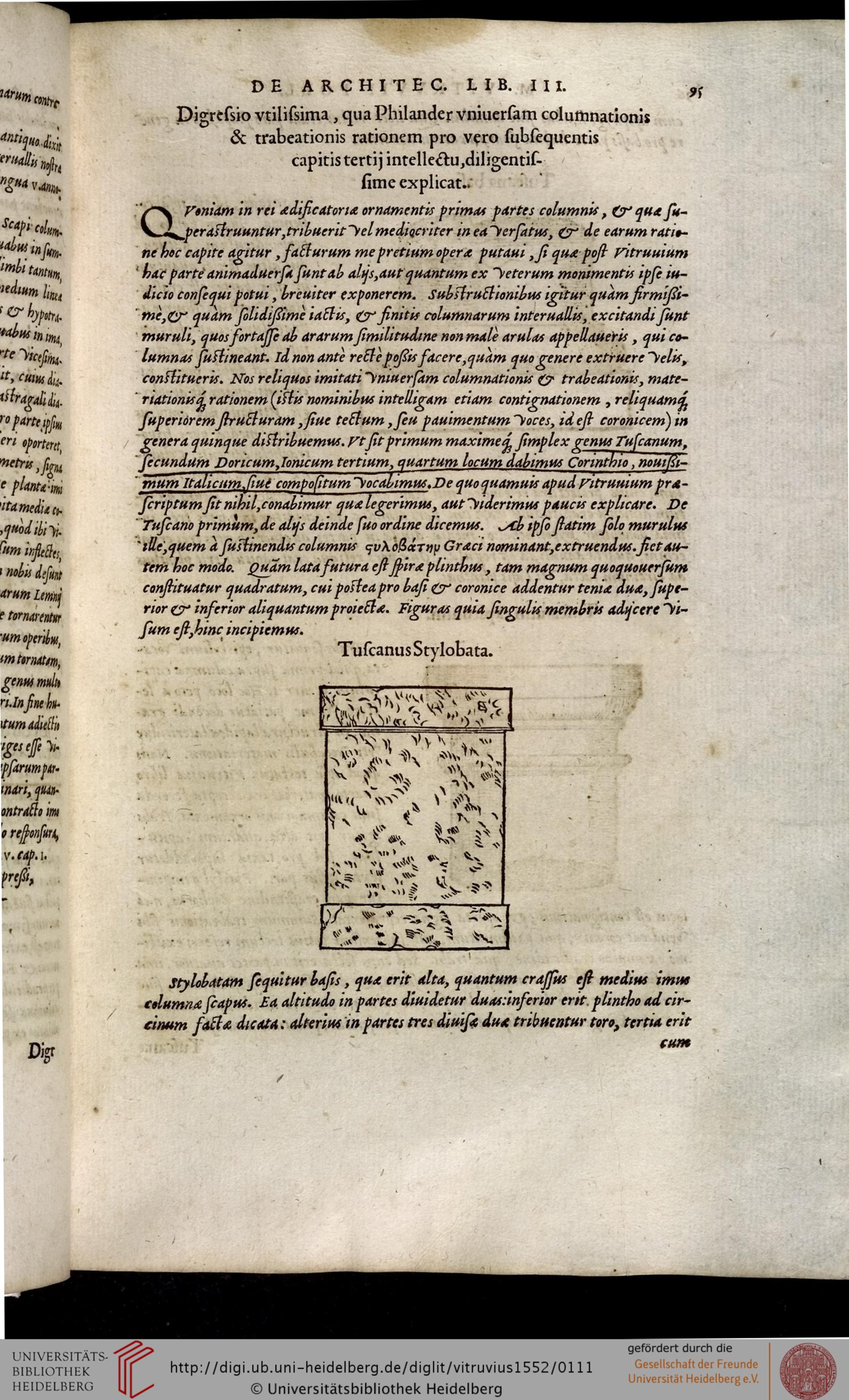

The Vitruvian commentary written in Latin was not intended for workers ; that is why the text dominates and the illustrations are of minor importance including in the Digression, the most illustrated text. The mediocrity of the woodcuts, due partly to the small format of the book (in-8°) is particularly noticeable in the representation of the orders. The engravings of the complete order are imprecise and rarely allow one to distinguish the different parts described in detail in the text (mouldings of pedestals, bases and capitals) (Fig. 3).

It even happens that the illustrations of details show differences in relation to the engraved part in the complete order or that the diagrams do not correspond to the text. Lastly, the proportions of the columns are not respected: for instance the Tuscan and the Doric have identical proportions. Clearly the draughtsman and the engraver did not work closely with the author. On the other hand the woodcuts in the fine reviewed and enlarged in-4° edition that Philandrier brought out at the print shop of Jean de Tournes in Lyon in 1552 are more meticulous, indicating the hand of a talented draughtsman, Bernard Salomon and of a more skilled engraver, but the fact remains that they are still imperfect and correspond badly to the text (Figs 4, 5).

Some illustrations are reversed. If the general representation of the five orders, such as the details of their parts corresponds more closely to the text, the proportions of the orders are not respected except for the Doric order, even though the book is in a larger format. Since the orders are almost represented at a constant height, precision diminishes with the width of the diameter, which could explain the increasing deviations in the Corinthian and composite orders, more slender (Fig. 6). Whether it is in the 1544 edition and its Parisian reissue in 1545 or the enlarged version of 1552, the engravings do not give an account of the text.