With the European maritime expansion of the fifteenth century onwards came the need for explorers and colonialists to represent the three-dimensionality of unknown worlds to those who stayed at home. Various visual devices were put to the task of communicating the appearances of newly claimed territories, including maps and drawings. Sometimes, artists would join maritime expeditions with the very purpose of visually representing heretofore unknown landscapes, peoples, animals, and plants. Confined to the two dimensions of paper or canvas, theirs was the job to convey in a lively and precise manner the fullness of what they encountered overseas.

The journal of the ship Gelderland is an excellent example of the ways European merchants and explorers translated their first impressions of far-away parts of the globe to the two-dimensional pages of a book. The two-volume journal, now kept in the Nationaal Archief in The Hague, is exceptional for the many drawings it contains. The ship Gelderland was part of a fleet of five vessels that sailed from the Netherlands to the East Indies in 1601-1603 with the aim to engage in the Moluccan spice trade. Its drawings record a variety of landscapes, animals, and objects encountered on the two-year journey.

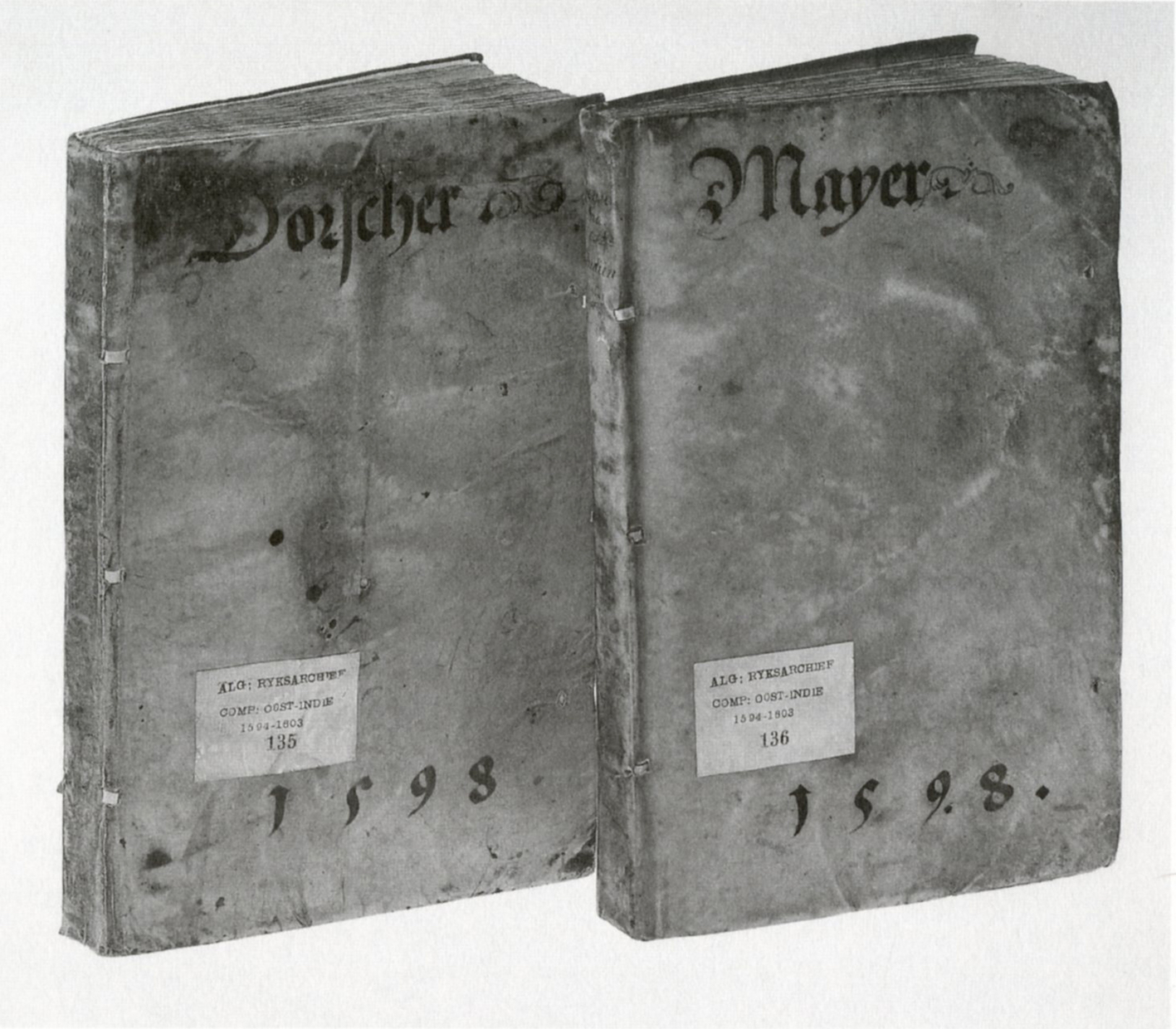

The two volumes (inventory 1.01.04, numbers 135 and 136 are bound in parchment and carry the titles Dorscher and Mayer, indicating that they were originally destined for ships with these names (Fig. 1).

How the journal ended up on the Gelderland is unclear. The 100 illustrations across the two volumes were in all likelihood drawn by Joris Joosten Carolus, also known as Laerle.

An otherwise obscure figure, Laerle was born in Bruges but lived in the northern town of Enkhuizen by the time the fleet took off. Like so many artists employed by the later Dutch East India Company (VOC), he had joined the expedition as a sailor. When, near the island of Mauritius, he proved inadequate at this job, he was relieved from his duties and began to draw.

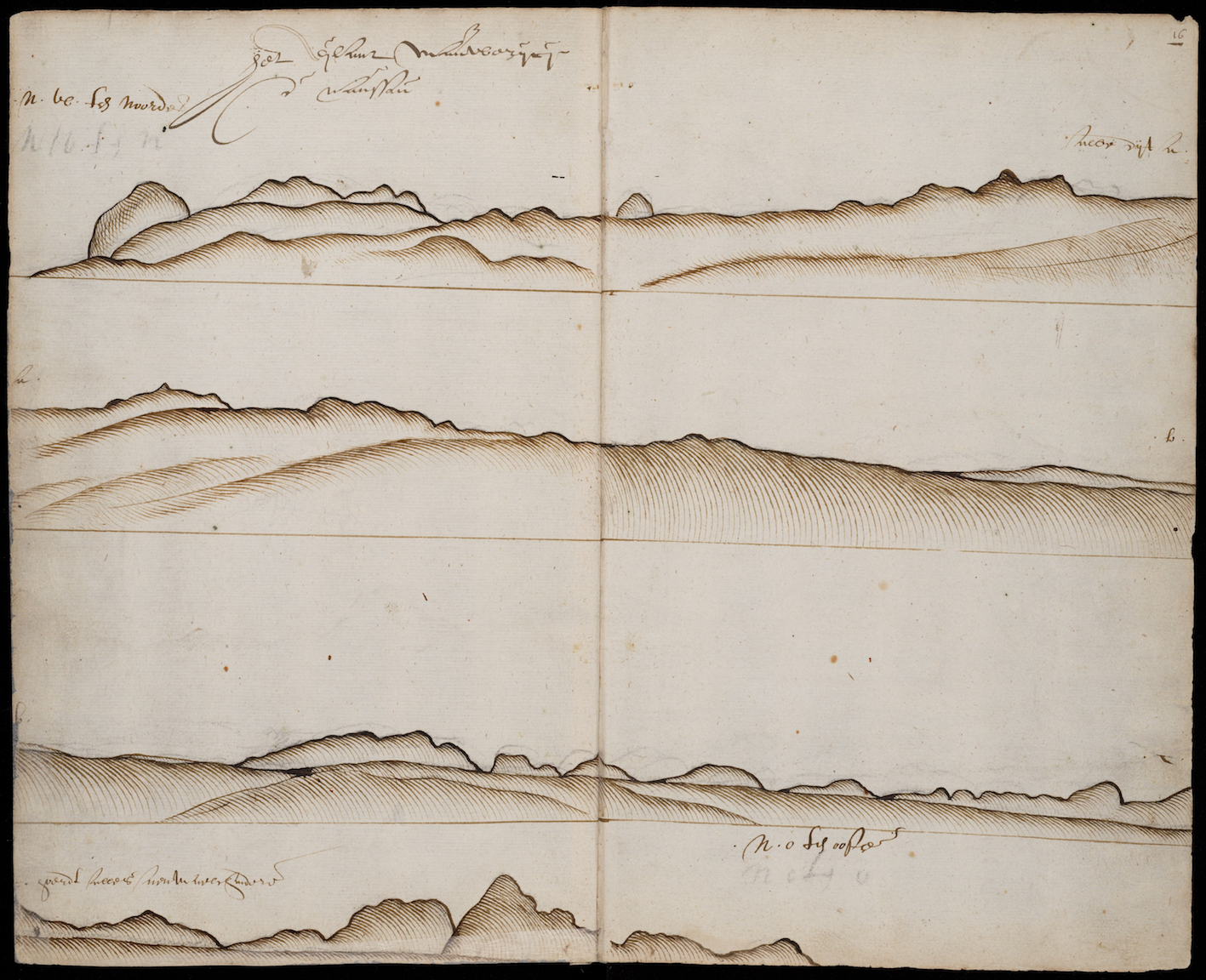

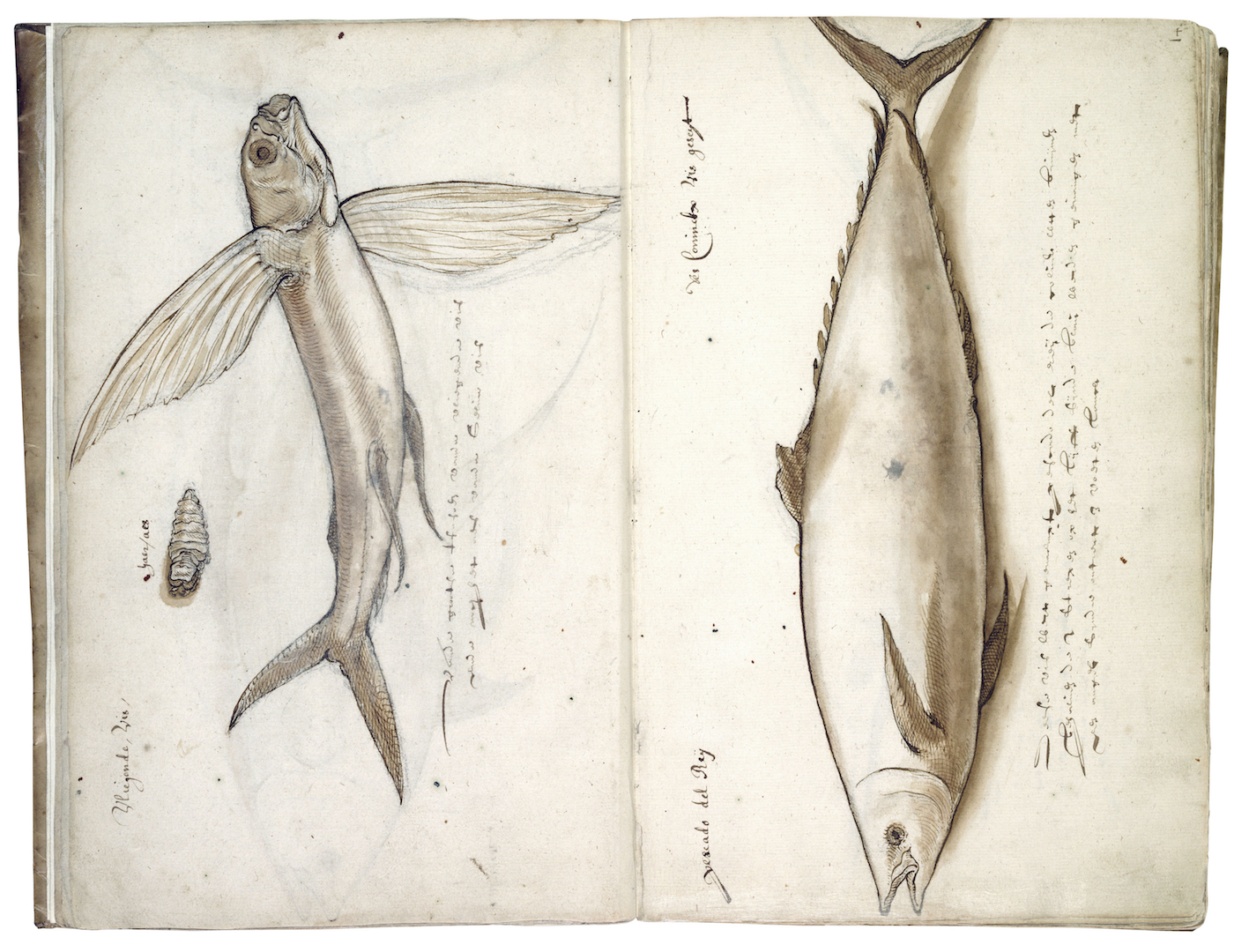

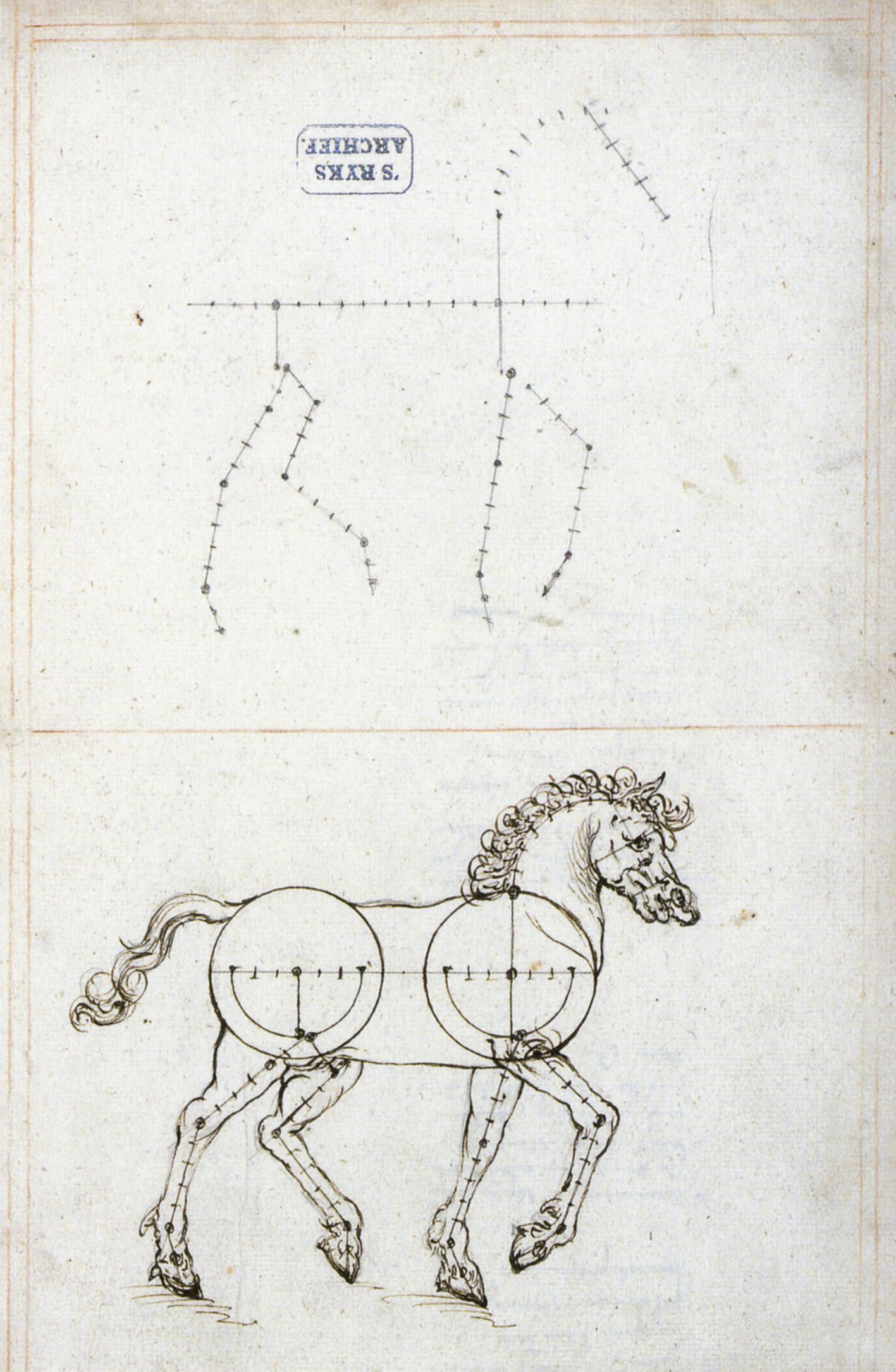

Perry Moree, the recent editor of the journal, distinguishes various categories of drawings: coastlines and harbours (Fig. 2), animals (birds, fish, and other sea creatures) (Figs 3-4) and other subjects, including diagrams of human and horse proportions (Fig. 5). In reality, Laerle did not fully organise his drawings by subject matter, and series of coastlines are interspersed with drawings of animals and other subjects.

The depictions of coastlines seem to have had a utilitarian purpose, meant to document the appearance of islands, mountains and capes as they offered themselves to those on board the ship. The drawings are often simple. Without exception, Laerle indicates the water line and horizon with a single ruled line, adding the outlines of mountains and hills on top. In the beginning, the land masses are coloured with ink washes and crayon, as is the case in the pages dedicated to the Madeira archipelago. This was the first place of interest on the route, reached on 13 May 1601 as Laerle points out in a caption (Fig. 6).

He uses ink lines and washes to indicate depth within the land masses, and even adds a dark, threatening cloud above the main island, so that it almost seems to have the same solidity as the mountain over which it is floating. In later drawings, Laerle was to let go of references to the weather, focussing solely on land masses, indicated economically with a minimum of parallel hatchings.

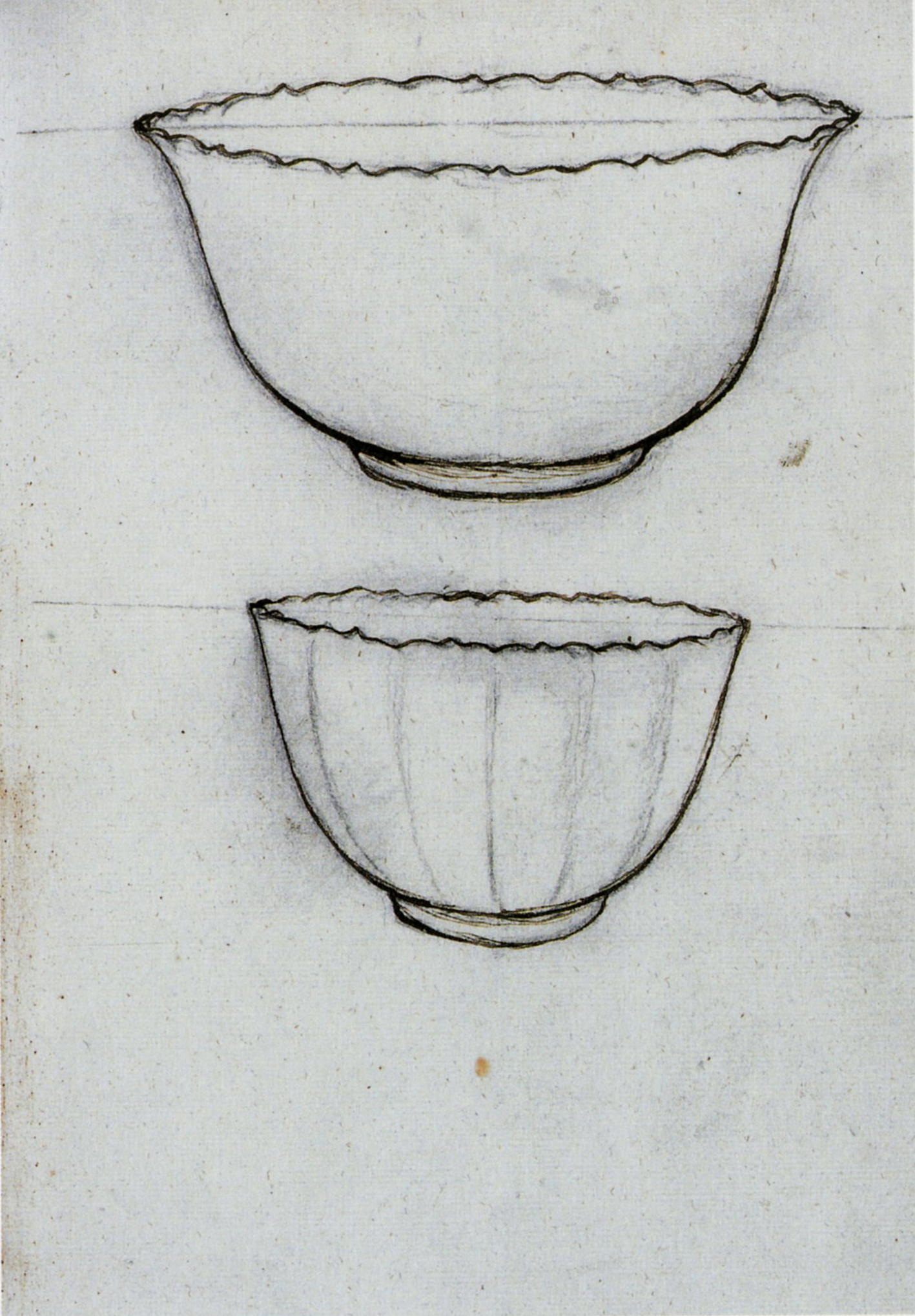

When it comes to thinking in three dimensions, of great interest are a series of drawings depicting porcelain wares (Figs 7-8). Next to spices, porcelain was an important type of good for those embarking upon the East Indian trade. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese had been importing Chinese porcelain for decades, and at the time, it could be found, albeit still in low numbers, in every major European collection. The type of porcelain reaching Europe at the time of the Gelderland’s expedition was primarily kraak porcelain, so called after the ships – caracas or kraken – that imported the fragile material. The blue-and-white porcelain, which hailed from the town of Jingdezhen in northeastern China, was deeply appreciated all over Europe for its thinness and translucency. It is no surprise, then, that the crew of the Gelderland would also have been interested in the material, and that Laerle would have drawn it – but to what purpose did he do so?

The artist devoted four drawings to porcelain, grouped together at the beginning of the Mayer volume. While two of them consist merely of outlines, two others use colour, and they very succesfully suggest volume and depth, providing the objects with a tactile quality. The artist has cared little for the porcelain’s decoration: only one drawing (FIg. 7) shows a bird surrounded by flowers. Given its circular shape, this probably records the interior decoration of a bowl or cup. The relative dearth of decoration on Laerle’s drawn porcelain objects is remarkable: kraak wares and other Chinese porcelain imported into Europe at the time tended to be busily decorated in blue underglaze paint, dividing the often circular objects into compartments and depicting floral shapes, animals, human figures and more. Laerle, instead, seems to have been interested mainly in the shapes of the objects.

The two coloured drawings (Figs 9, 10) each show three sets of objects, arranged one above the other on a central vertical axis. The blue drawing shows a cup, then a bowl perched on top of a cup, and then another bowl resting on a cup turned upside down. Volume is delicately indicated, using a combination of black hatchings and blue washes to show the porcelain’s soft roundings, undulating rims, and shadows. The yellow-brown drawing similarly shows objects stacked on top of one another, and gives even more attention to the finely molded rims, which the artist has given white highlights. Did Laerle make these drawings to record objects purchased by the Gelderland’s crew? This is possible, although the practical need for such drawings is unclear. Another hypothesis is that someone made these drawings not at sea but before the expedition set off. In that case, the images would have served as a memorandum, indicating the forms of porcelain objects most desired in the Dutch republic. Whatever the reason behind their making, these drawings appeal in the twenty-first century for their minimalist aesthetic: with their focus on shape, not decoration, they evoke the tactile pleasure of artfully moulded three-dimensional things like no other.

Further reading

- The journal of the Gelderland:

Moree, Perry. Dodo’s en galjoenen: De reis van het schip Gelderland naar Oost-Indië, 1601-1603. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2001.

- Other:

Bok, Marten Jan. ‘European Artists in the Service of the Dutch East India Company’, in Mediating Netherlandish Art and Material Culture in Asia, edited by Thomas Dacosta Kaufmann and Michael North, 177-204. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014.

Campen, Jan van, Cordula Bischoff, and Titus Eliëns (eds). Chinese and Japanese Porcelain for the Dutch Golden Age. Zwolle: Waanders, 2014.

Canepa, Teresa. Silk, Porcelain and Lacquer: China and Japan and their Trade with Western Europe and the New World, 1500-1644. London: Paul Holberton, 2016.

Corrigan, Karina, Jan van Campen, and Femke Diercks (eds). Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.