Note: The present article is a revised and extended excerpt of my talk ‘From Anatomy to Embroidery: Printed Colour in Books and Periodicals’ for the conference Printing Colour 1700–1830: Discoveries, Rediscoveries & Innovations in the Long 18th Century, London, 10–12 April 2018. For abstract and programme check the website.

The relation between colour printing and three-dimensionality (3D) is that colours create perspective, much more than and different from how tonal gradations of grey can. In intaglio printing this shows for the first time in the colour printed landscape views produced by the workshop of Johannes Teyler (1648–1709?) that was active in Holland from c.1685 to 1697. The colour hues make them appear much more spatious than prints in black (see Fig. 4). A decade later the German painter Jacob Christoff Le Blon (1667–1741), then active in Amsterdam, developed his tri-chromatic system, over-printing three mezzotint plates inked in blue, yellow and red (in that order) in register on white paper, the impressions showing all possible compound hues. The colour printing makes them appear more vivid and lifelike, a characteristic made use of in eighteenth-century anatomical illustrations. Le Blon’s invention brought colour printing to a new level developing to the CMYK system used in modern printing, i.e., printing images in overlapping layers of Cyan, Magenta and Yellow, with a Key in black.

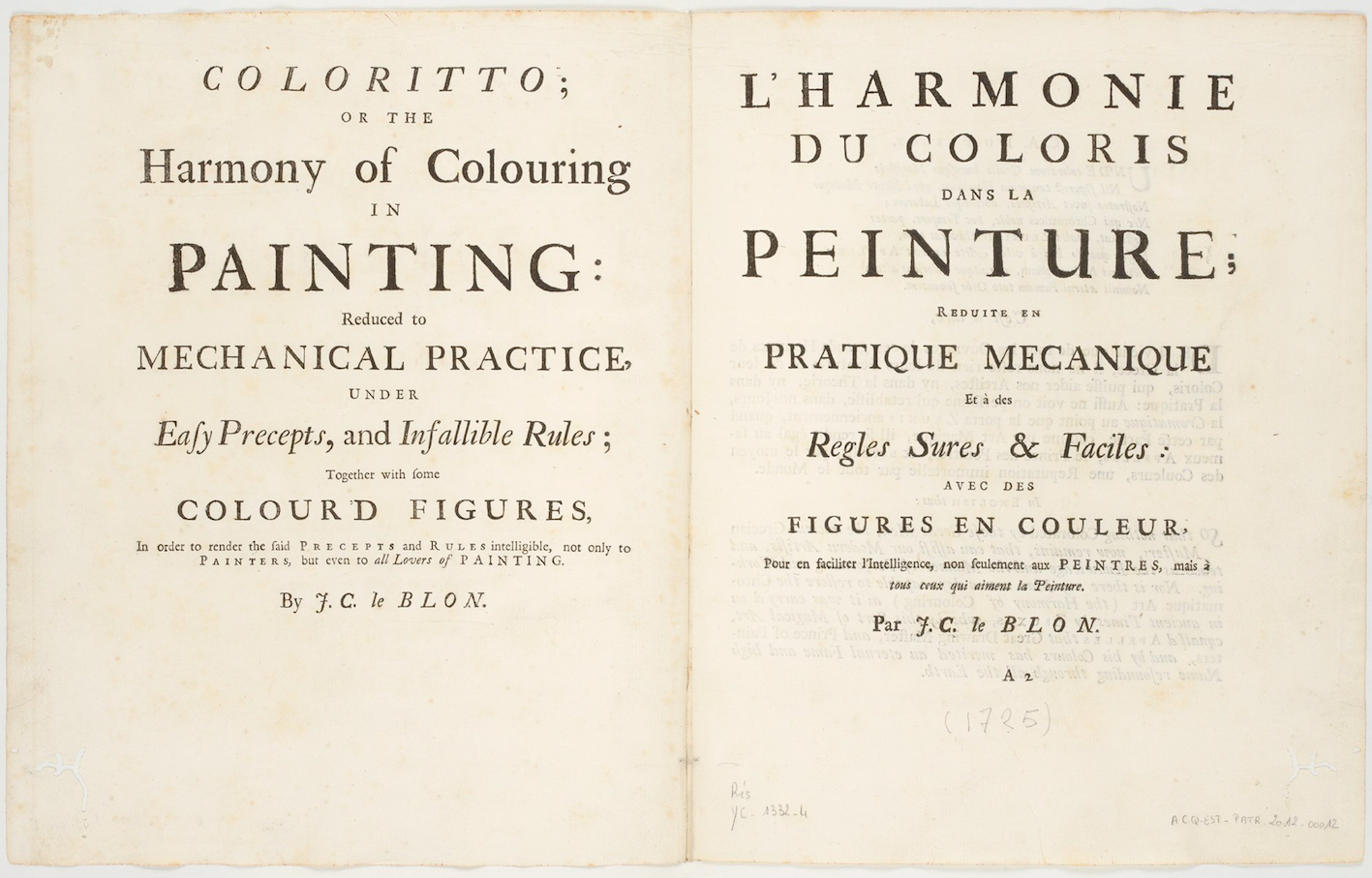

In 1725, when Le Blon was in London, he published his bi-lingual Coloritto; or the harmony of colouring in painting = l’Harmonie du coloris dans la peinture (London, 1725). The book is a manual on how to paint white human skin. However, it stirred much confusion from its publication until the present day, with people stating that it was ‘a manual on colour printing’ (it is not), that Le Blon based himself on ‘Sir Isaac Newton’s three-colour theory’ (Newton did not postulate a three-colour theory) and that the illustrations each are printed from ‘four’ differently inked plates (maximum two, all other colours are applied by brush).

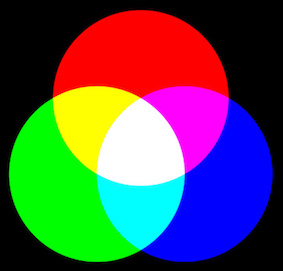

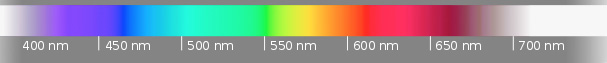

Starting with some colour theory, two fundamentally different physical processes exist for creating colour hues. Additive colour mixing concerns mixing coloured lights until white light containing all colours appears. It is the modern RGB system used for computer screens, televisions, digital projectors, digital cameras and mobile phones (use a strong magnifying glass to see the red, green and blue LEDs).

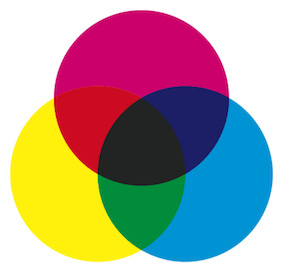

Subtractive colour mixing (the present CMYK system) concerns mixing coloured inks or paints until a dark grey hue appears. Notice also the different primary colours of light and of paint, and their mixtures: the primary colours of red and green light give yellow light, while the primary colours of red (magenta) and yellow paint give orange paint.

The process of inking matrices in more than one colour, the adjacent colours touching or with a narrow gap in between, and printing them in one run is called à la poupée (with a dolly, i.e., with a small stuffed inking ball). The term itself came in use only after 1900, but examples of à la poupée inked type, woodblocks or copperplates are found from the middle of the fifteenth century. Colour combinations were usually limited to two inks, such as black-red or blue-red, seldom three. The process was not used much until Johannes Teyler developed a method of à la poupée inking engraved and etched copper plates with up to nine vivid colours. His workshop was active in Holland from c.1685-1697. Amsterdam publishers started using his process for single-leaf art prints and printseries from 1695. From there it disseminated to other European countries and was especially popular for English dotted prints and illustrations in French botanical and zoological books, from the 1780s until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Le Blon had settled in Amsterdam in 1705, where he developed tri-chromatic printing. He moved to London c.1718 and to Paris in 1735. In both cities he attracted interest in his manner and was granted royal English and French privileges for his process.

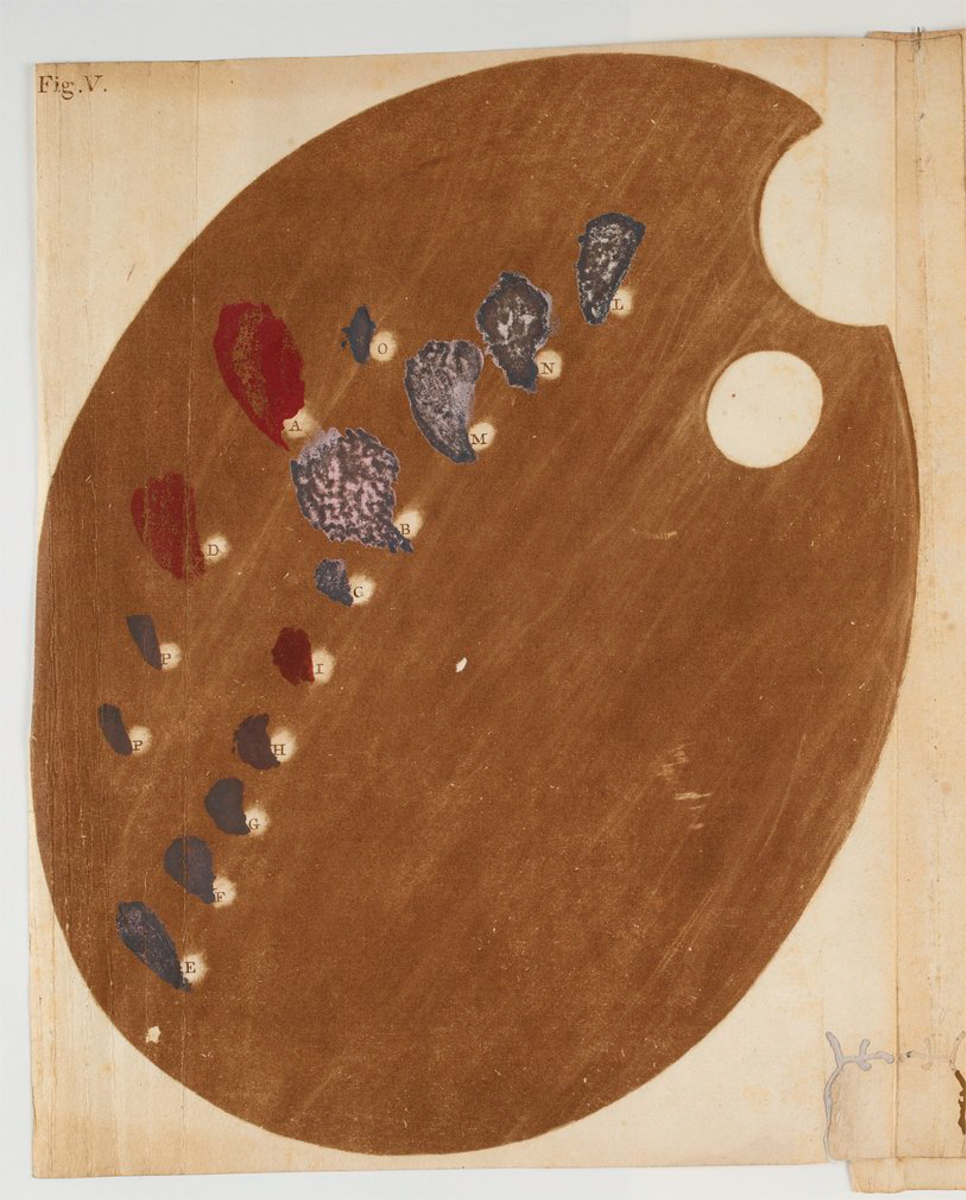

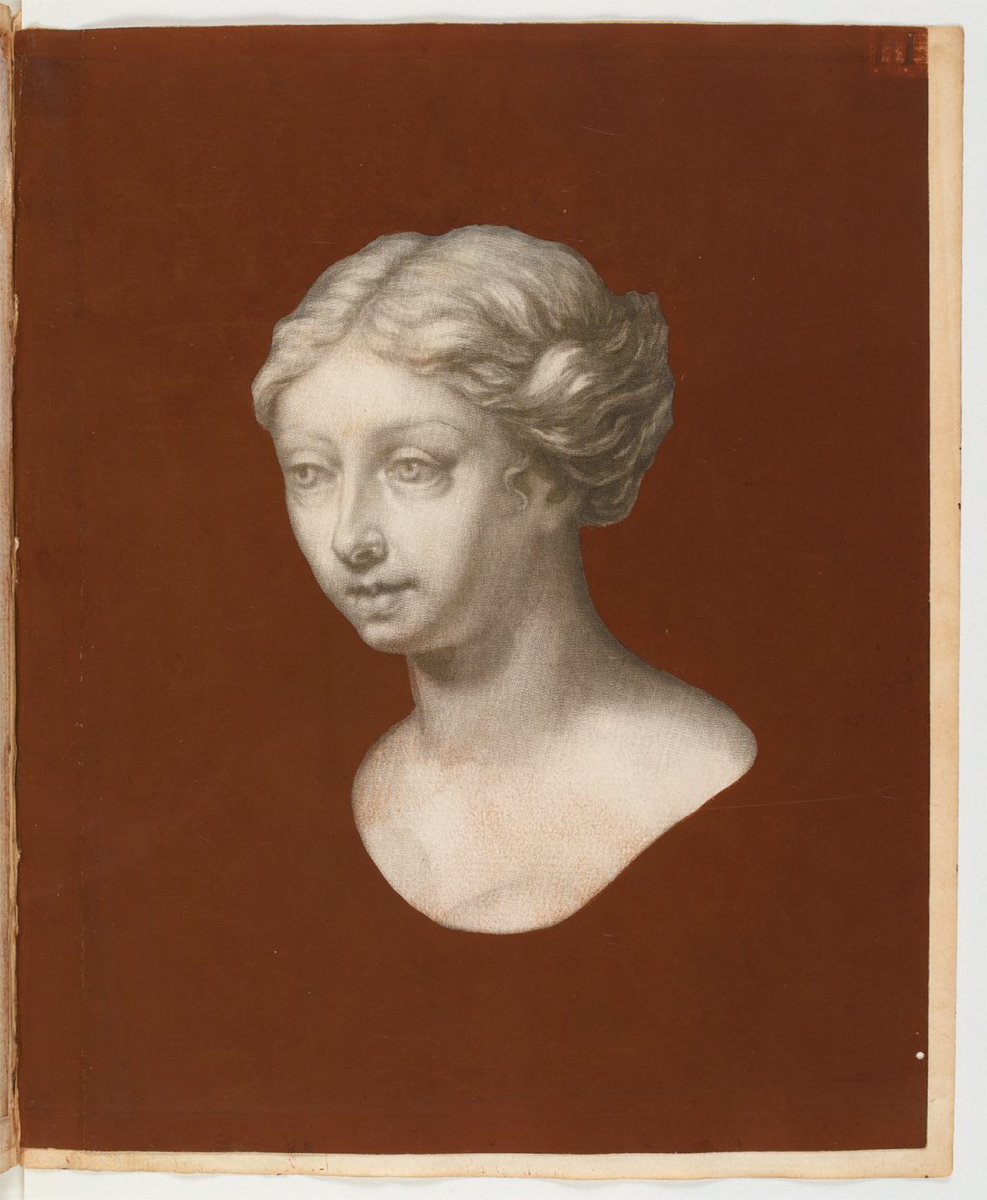

In his Coloritto Le Blon explained how to mix the primary colours blue, yellow and red paint to create compound hues of white human skin. Plates I–IV of Coloritto are four mezzotint portraits depicting a young woman demonstrating his ideas on the use of colour paints. Plate V has the palette printed in brown with the paint mixtures he advocates brushed in. Note that the watercolours containing leadwhite have turned grey over time. A number of copies of the book have an Appendix with further instructions, two more portraits and two more palettes.

The portraits are printed from the same two mezzotint plates, after a skin-coloured plaster cast buste (p. 8, “an Head of Plaister stain’d with the Colour of Flesh”). Plate I is an impression of the first mezzotint in black only. The impression is made early in the edition, as the blacks are still deep the mezzotint has not worn, yet.

Plate II appears grey, due to wear of the mezzotint, and has the background brushed in brown watercolour. The irises look pale, because they have been scraped and polished.

For Plate III an impression of the first (worn) mezzotint in black was over-printed in register with a second mezzotint in red. This second copper plate had hardly worn and the impression clearly shows it was inked in purplish-red. The two ink layers create compound hues, except for the irises that were left blank in the red mezzotint. The background is coloured with brown watercolour.

For Plate IV the black mezzotint was over-printed with the red one. Meanwhile the second copper plate had worn a little, making its hue less intense and giving a better colour balance. The background was hand-coloured and the woman’s face has the lips accentuated in red, the irises are filled in (for which reason they should not have been present too strongly in the plates), and the eyelashes, eyebrows and hair were painted.

The two portraits in the Appendix (not present in the Bodleian copy) were both printed in black, over-printed with a second plate inked purple-red and were finished by hand-colouring. None of the six portraits was printed in three or four colours and the palettes were all three inked in brown with the colour dashes painted in.

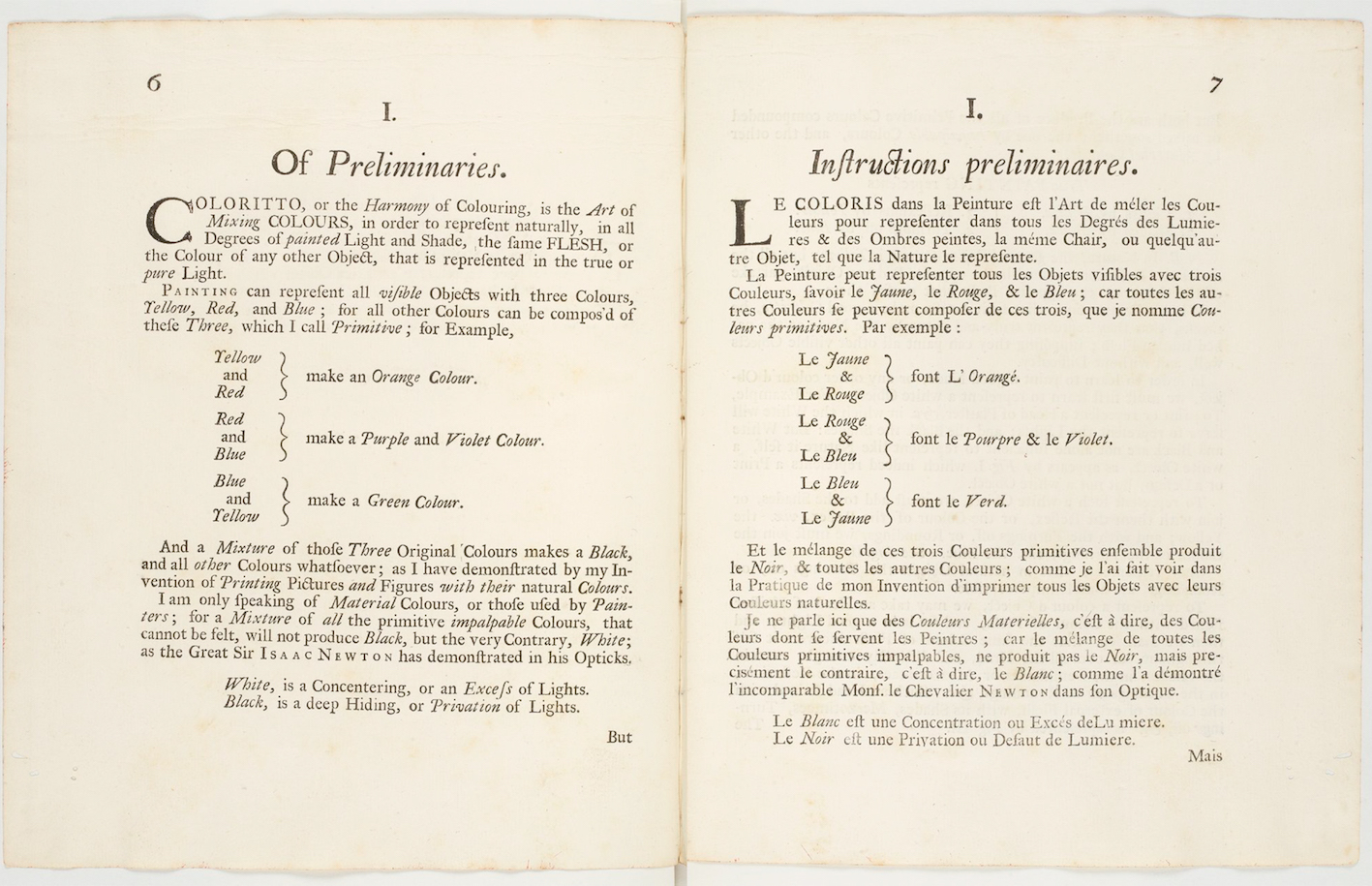

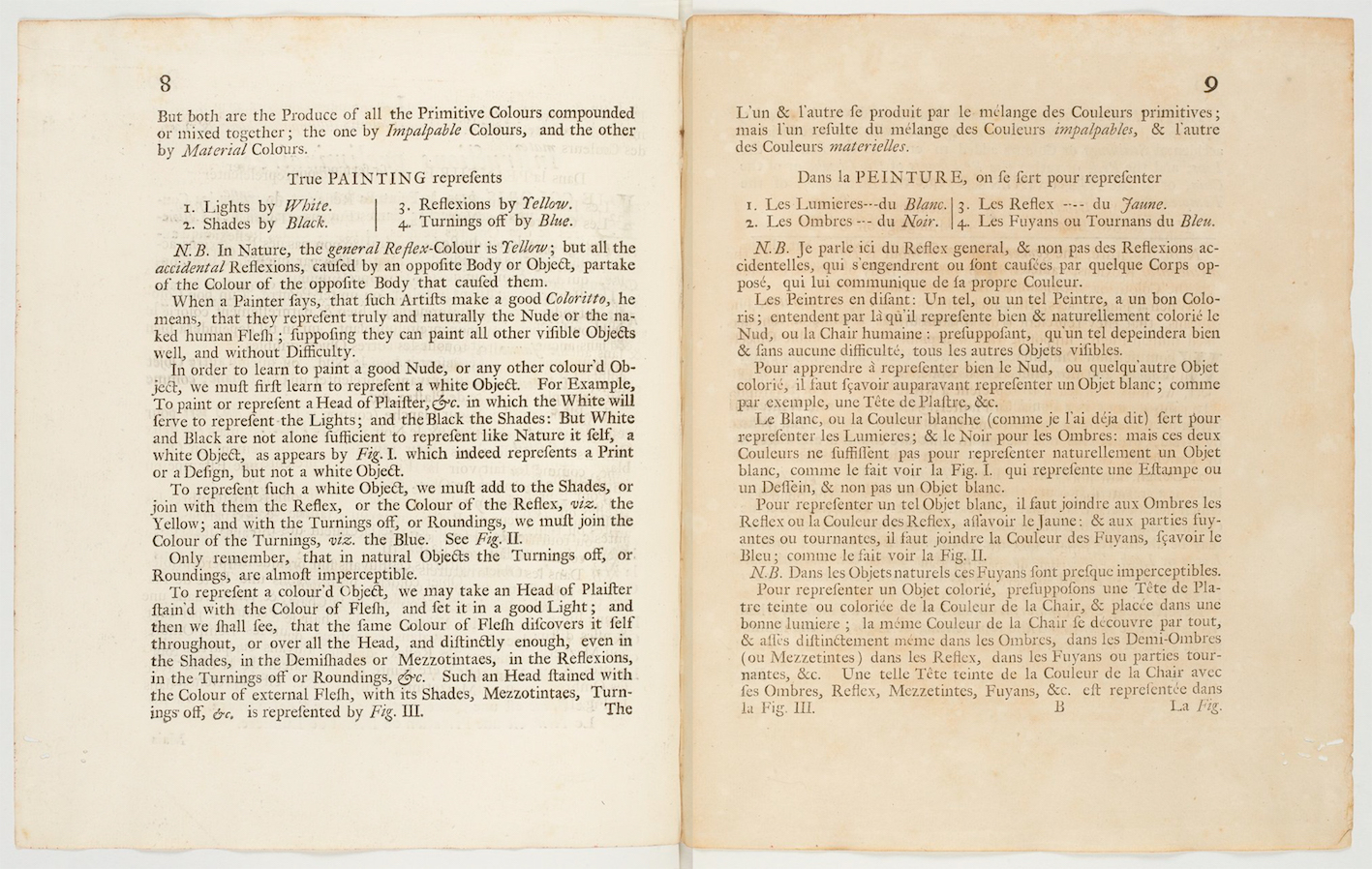

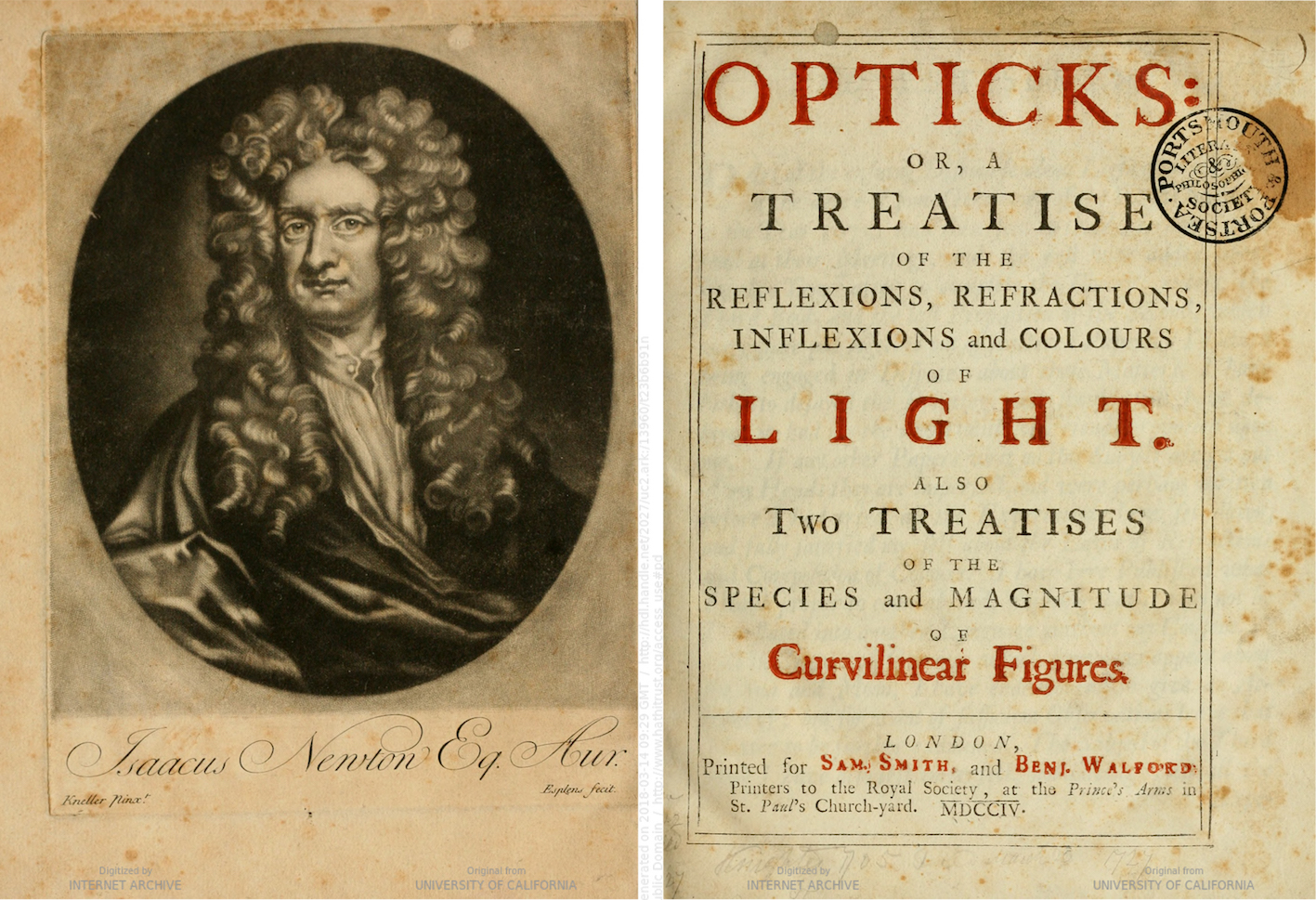

It is often, until the present day, said that Le Blon merely followed the research of the famous Sir Isaac Newton. Pages 6 and 8 (in English) and pages 7 and 9 (in French) of the first chapter of Coloritto show what Le Blon was working on and where he and Newton differ. Le Blon indeed referred to Newton, correctly mentioning that the mixing of all – so not just three – colours of light will create white light “[p. 6] as the great Sir Isaac Newton has demonstrated in his Opticks”. But Le Blon marked the difference stating that he himself was “[p. 6] only speaking of Material Colours, or those used by Painters”.

Le Blon explained in his manual how “[p. 6] PAINTING can represent all visible Objects with three colours, Yellow, Red and Blue; for all other Colours can be compos’d of these Three, which I call Primitive”. Yellow mixed with red makes orange, etcetera, see the tables on pp. 6 and 7. This was common knowledge for painters and generaly accepted in seventeenth-century treatises on colour, but in his Coloritto he demonstrated its consequent use in painting white human skin.

New was his invention to reproduce oil paintings by means of a system of over-printing three mezzotint plates with transparent blue, yellow and red inks on white paper, the overlapping layers rendering all required hues. For example, if a layer of transparent yellow ink is printed over a layer of blue ink on white paper the whole appears a bright green. This is similar to glazing a transparent layer of yellow paint over a layer of blue paint, and as a painter Le Blon will have been familiar with the technique of glazing.

Le Blon correctly expressed the difference between mixing paint and mixing rays of light, because he stated that “[p. 6] a Mixture of those Three Original Colours makes a Black, and all other Colours whatsoever; as I have demonstrated by my Invention of Printing Pictures and Figures with their natural Colours”, by which he means his tri-chromatic printing process. Otherwise he followed Newton when he stated that “[p. 6] a Mixture of all the primitive impalpable Colours, that cannot be felt [he means coloured lights] will not produce Black, but the very Contrary, White”.

And once more, on p. 8, the mixture of primary “Impalpable Colours” is ‘additive’ colour mixing of light rays and the mixture of primary “Material Colours” is ‘subtractive’ colour mixing of paints.

After 38 years of research Newton published his Opticks (1704), a treatise on the behaviour of ‘light’, as it clearly states on the title page.

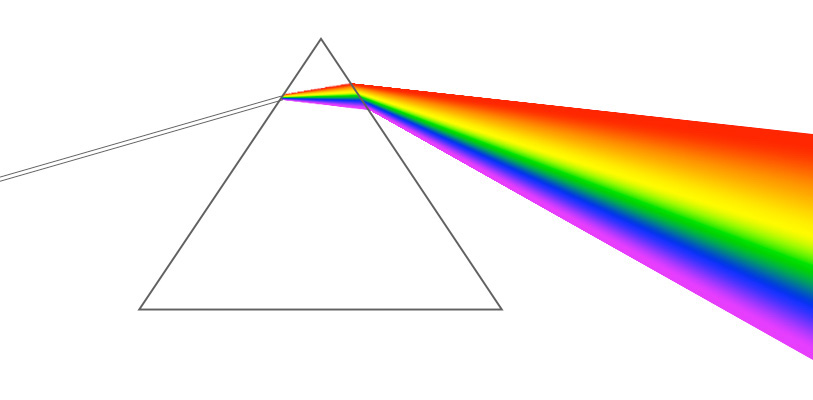

Newton observed the behaviour of light, dividing the rays of white light into a spectrum by means of a prism, as shown here. This spectrum is a continuous series of wave lengths, from the longest wave lengths on the red side at 750 nm to the shortest on the violet side at 400 nm, which creates millions of colour hues.

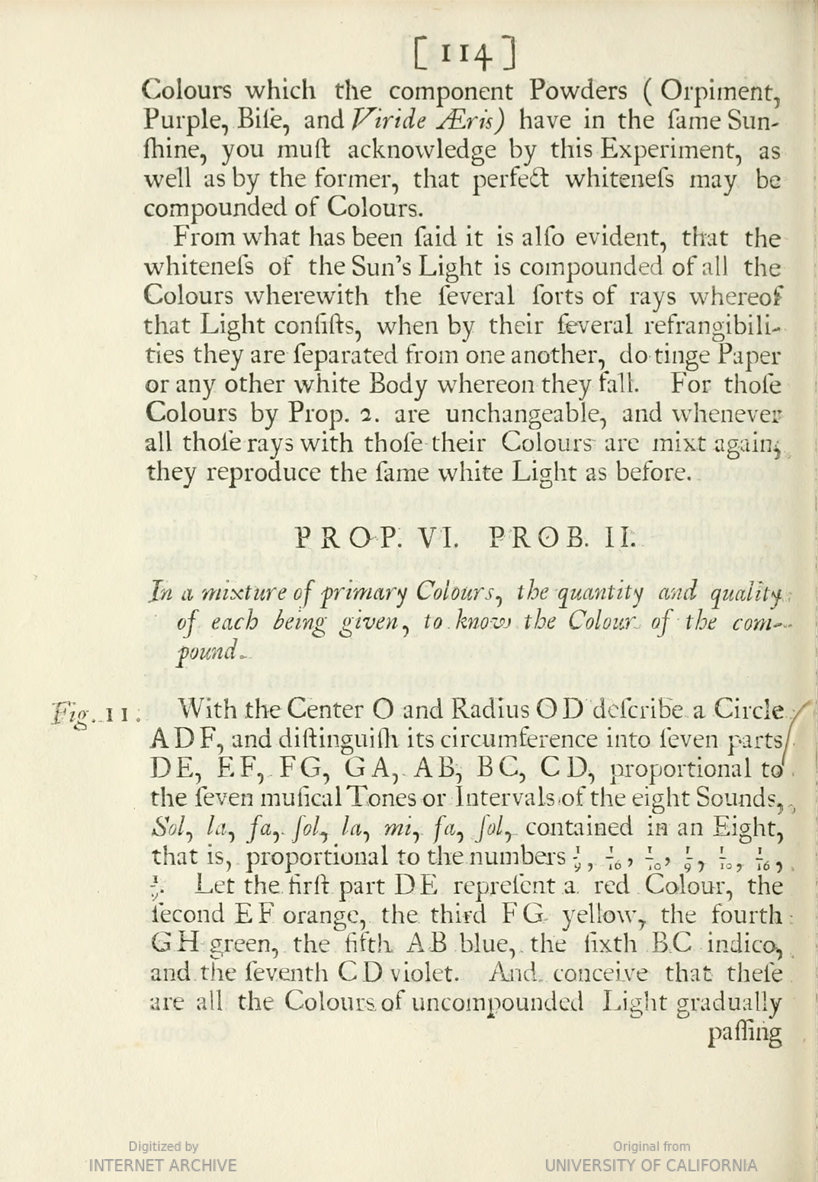

In 1672 Newton had stated in an article that there were innumerable ‘original colours’, similar to what the earlier slide showed. In 1704 he had brought that back to seven colours (‘The First Book of Opticks’, p. 114): red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. He compared this with “the seven musical tones”.

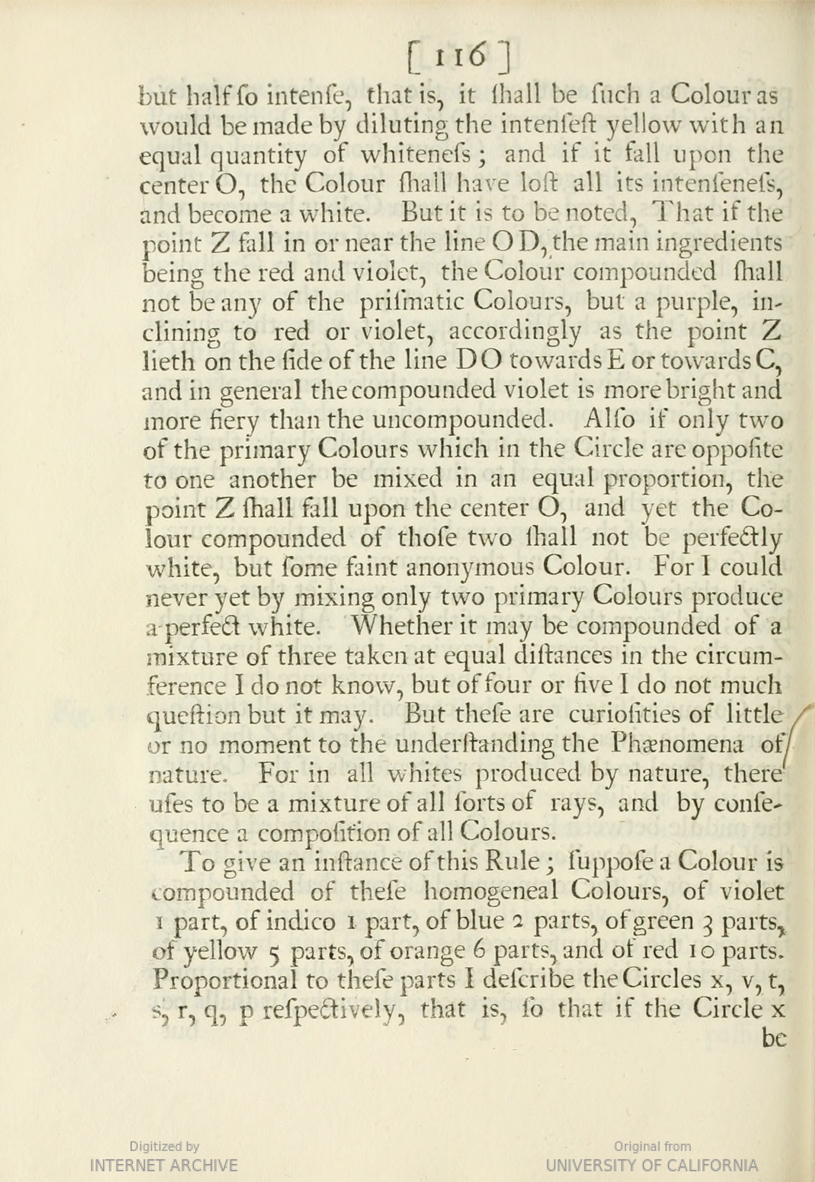

On p. 116 he observed that if two colour rays not removed too far from each other were mixed the intermediate colour appeared. He observed that two opposite colours produced “some faint anonymous Colour”. He did not know if three colours of light could create white light. Important to him was that “in all whites produced by nature, there uses to be a mixture of all sorts of rays, and by consequense a composition of all colours.”

Newton’s aim was to unite all colour appearances in one universal theory, which is not possible, as we now know, because they concern different natural phenomena. He did observe the reflection of light on pigment powders, but did not discuss mixing colour paints with the intention to create other colours. His study on light could not have supported Le Blon in developing tri-chromatic printing, as Newton did not compare additive to substractive colour systems and – thinking in ‘seven’ primary colours – and therefore did not invent a ‘three’ colour theory. He did not even try mixing three colours of light, let alone come up with suggestions on how to print in three colours.

If Newton discussed the behaviour of light and Le Blon explained the process of mixing three colours of paint, where, then, does the idea come from that Le Blon based himself on Newton? In 1735 Le Blon arrived in Paris from London and applied for, and was granted, a French royal privilege for his process. A year later young engraver Jacques-Fabien Gautier arrived from Marseille where he had observed block printing fabric in multiple colours. It had inspired him to do something similar in printmaking. Because of this interest he was invited to work for Le Blon in 1738, but left after six weeks, long enough for him to learn Le Blon’s tri-chromatic manner.

Immediately after Le Blon’s death on 15 May 1741 Gautier applied for a royal privilege for colour printing instead of Le Blon, was granted it, saw it revoked, but eventually acquired it. Gautier claimed to be the inventor of printing with four plates, i.e., including an extra black plate (but see plates III and IV of Coloritto) and was opposed strongly. A polemic in the Mercure de France about this lasted for years. Gautier kept on submitting letters to the editors promoting his case until they found it so annoying that they stopped publishing them.

In the course of this polemic he stated that Le Blon ‘had tried applying Newton’s theory on painting’. [Jacques-Fabien Gautier-Dagoty, ‘Lettre à M. de Boze, de l’Académie Françoise, & Honoraire de l’Académie de peinture & sculpture, Garde des médailles & pierreries du Cabinet du Roi, &c’, in Mercure de France, (July 1749), 158–72: see p. 159].

He stated more emphaticaly that ‘Le Blon blindly followed Newton’s system. He banned black from the class of colours; he ridiculously considered that the union of material colours created black, while the union of coloured lights created white; an error causing not only Le Blon, but all followers of this philosophy to make the same big mistakes’. [Jacques-Fabien Gautier-Dagoty, ‘Lettre à l’auteur du Mercure, & Réponse à la Letttre [sic!] anonyme insérée dans le premier volume de Décembre, sur l’invention d’imprimer les Tableaux’, in: Mercure de France, (Jan. 1756), 2:189–203: see p. 199]. In other words, Gautier not only rejected Le Blon’s ideas, but also Newton’s.

Background for this controversy was that Newton’s Opticks was first favourably received, which developed into vigorous debates when found that his ideas differed from practice. Attempts to apply one colour theory for both light and paint failed, of course, because two different physical phenomena are concerned.

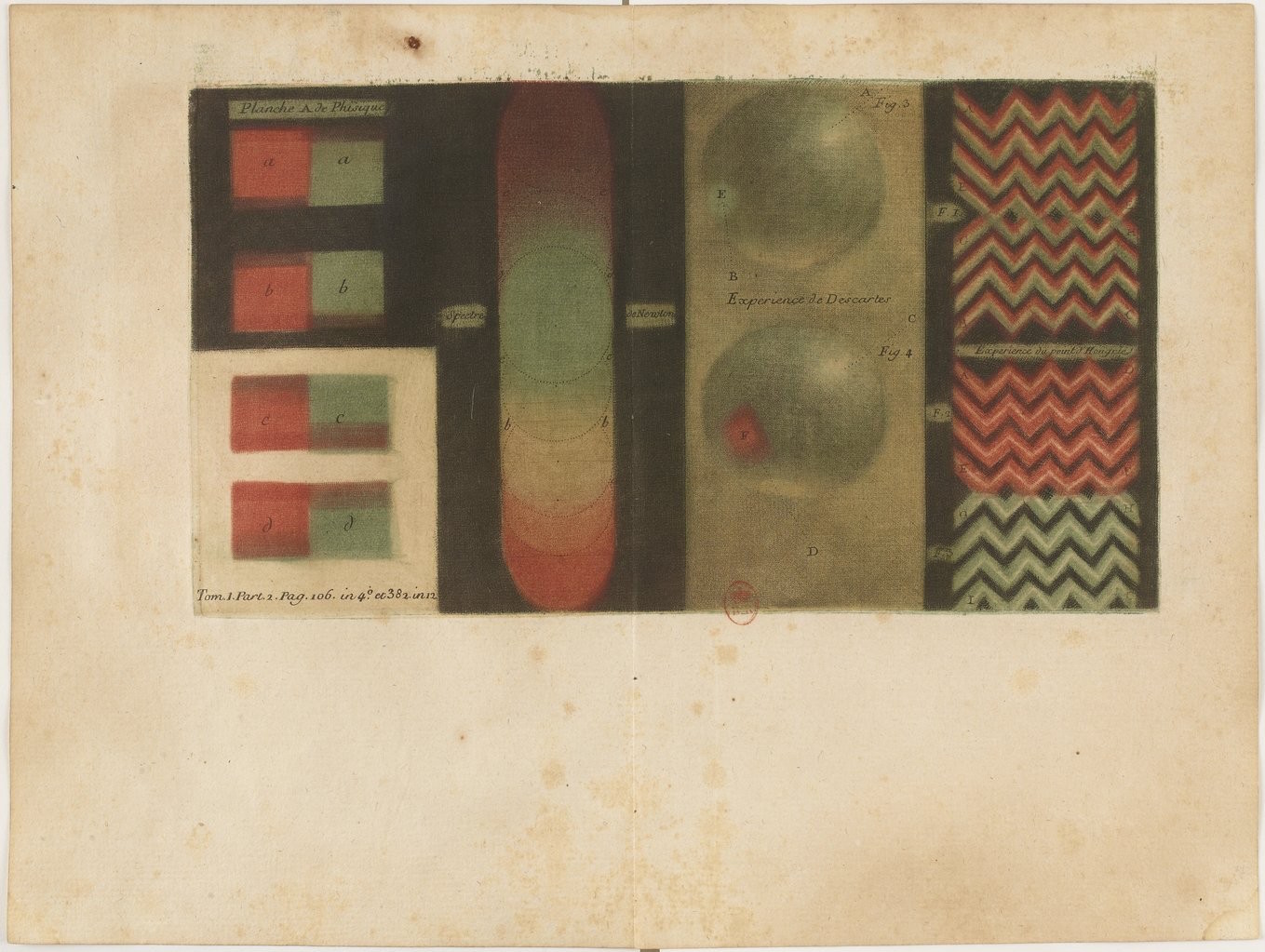

Gautier got involved in the debate and published an article (in his own scientific periodical), in which he commented on Newton’s observations. [Note: Jacques-Fabien Gautier-Dagoty, ‘La cause des couleurs selon Newton’, ‘La cause des couleurs selon mon Systême’, [etc.], in Observations sur l’histoire naturelle, sur la physique et sur la peinture, 4 vol., Paris: Delaguette, 1752–1755, vol. II (1752), pp. 99–106.] Instead he proposed his own system based on the opposition of light and dark, and the two opposite colours of the spectrum red and blue.

Statements that Le Blon worked after a three-colour theory by Newton kept appearing throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century. However, as becomes clear from Newton’s own writings, he did not mix three primary colours of light, let alone paint, and did not postulate any three-colour theory. Le Blon, on the contrary, made a clear distinction between light and paint, between additive and subtractive colour mixing, and he developed a new colour printing manner based on painters’s practice.

Postscript:

Eighteen copies of Coloritto still exist today, half of which have an Appendix. Two copies formerly kept in German collections have been lost during the Second World War. Two more copies are mentioned in literature, but their present whereabouts are unknown. It is not known whether the disappeared copies had an Appendix or not. However, the edition of a mezzotint plate can be up to 300, if the printer takes care, but the impressions become paler and paler in the course of printing, as we see with the portrait plates in Coloritto. This means that the volume was produced in supposedly not more than thirty copies.

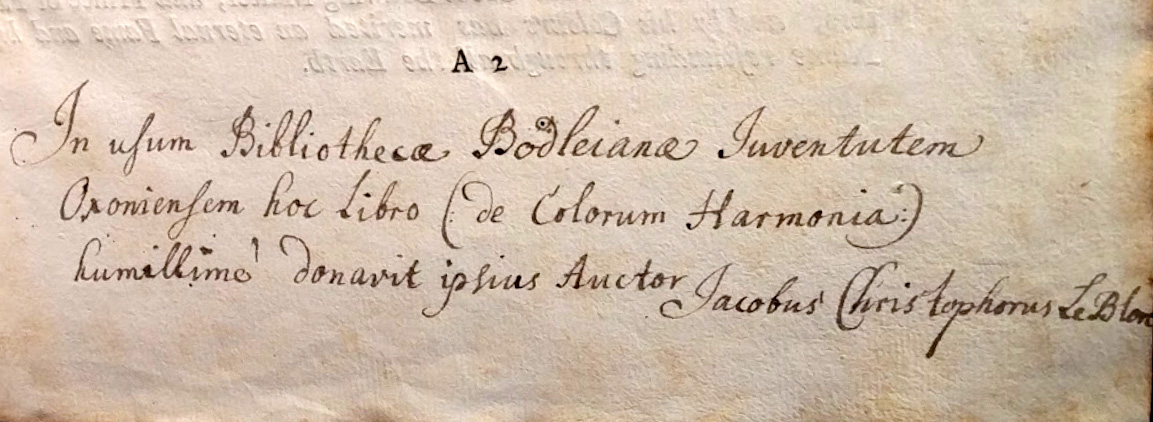

The Bodleian copy has a nice extra in the form of a dedication that shows it has been donated to the Library by Le Blon himself for use by the students. The inscription reads:

In usum Bibliothecae Bodleianae Iuventutem Oxoniensem hoc Libro (:de Colorum Harmonia:) humillime donavit ipsius Auctor Jacobus Christophorus Le Blon

In translation: ‘This book (of the Harmony of Colours) is very humbly donated to the Bodleian Library for the use of the Oxford youth by its Author, Jacob Christoff Le Blon’.

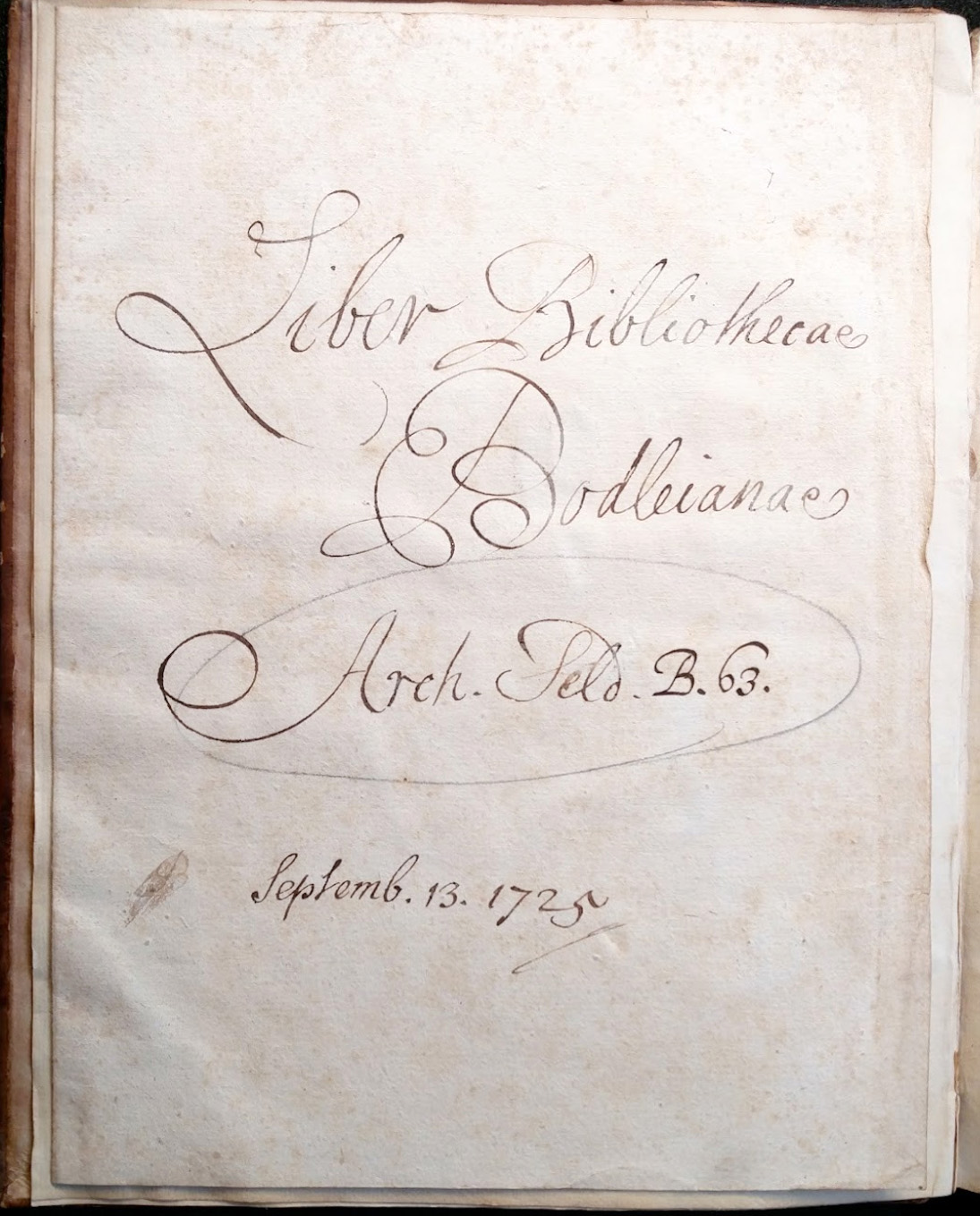

The volume’s ex libris, written on the verso of plate V with the palette, shows it entered or was donated to the library on September 13th, 1725: Liber Bibliothecae / Bodleianae / Arch. Seld. B. 63. / Septemb. 13. 1725. The present shelfmark is Arch. A.d.9.

Further reading

Otto M. Lilien, Jacob Christoph Le Blon, 1667–1741: Inventor of Three- and Four Colour Printing, Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1985.

Ad Stijnman (comp.), Johannes Teyler and Dutch Colour Prints, Simon Turner (ed.), Ouderkerk aan den IJssel: Sound & Vision, in co-operation with The Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2017, 4 pts. (The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450–1700).

Ad Stijnman and Elizabeth Savage (Upper), Printing Colour 1400–1700: History, Techniques, Functions and Receptions, Leyden: Brill, 2015.

For the copy of Coloritto of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, see here (scroll down to the bottom); without pl. I, with the Appendix but without its plates).

For the copy of Coloritto of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, DC, see here.

For the here reproduced copy of Coloritto of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Rés. YC-1332-4, see here.

For the here reproduced copy of Opticks, University of California Los Angeles, Library, QC353 .N48o 1704, see here.

For the here reproduced plate from Observations sur l’histoire naturelle, sur la physique et sur la peinture, see here.