Introduction

In the summer of 2017, the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine at the University of Minnesota was offered the opportunity to purchase an exciting rare volume from mid-Edo Japan: a full color anatomical manuscript depicting five full human figures and multiple individual organs and organ systems, dissected and described in paper. Created throughout the early modern period in Europe, flap anatomies were important paper tools for physicians, surgeons, and interested readers to understand the organization of organs and tissues in human and animal bodies in an era in which access to anatomical dissections was still relatively limited.

Although the Wangensteen has a substantial number of European flap anatomies, curators Lois Hendrickson and Emily Beck had never before seen an example from East Asia. Consultation with booksellers and experts in early movable books like flap anatomies confirm that this volume was likely modeled on a work by the German anatomist Johannes Remmelin, published in Dutch in 1667.

It was likely brought to Japan by Dutch traders in the late seventeenth century, and a Japanese translation of Remmelin’s work was published in 1772 by Motoki Yoshioki (also known as Ryōi). Between 1641-1853 under the Japanese policy of national isolation the Dutch were the only Europeans allowed to enter and actively trade on the island. In particular, Dutch books were in high demand and schools of Dutch-learning (or Western learning) known as Rangaku were operated across Japan.

The Wangensteen’s Japanese flap anatomy is unique when compared with the 1772 Japanese translation of Remmelin. The Japanese translation takes both the book form of a flap anatomy as well as the Dutch/European medical theory and translates it into a Japanese context. The Wangensteen manuscript, however, borrows the book form but replaces Western medical theory with Chinese medical theory that was dominant in Japan in this era. Undated and anonymous, this manuscript presents a series of tantalizing questions about the ways in which both book forms and medical knowledge traveled, were transformed, synthesized, and adopted in Europe and East Asia in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Description of the manuscript

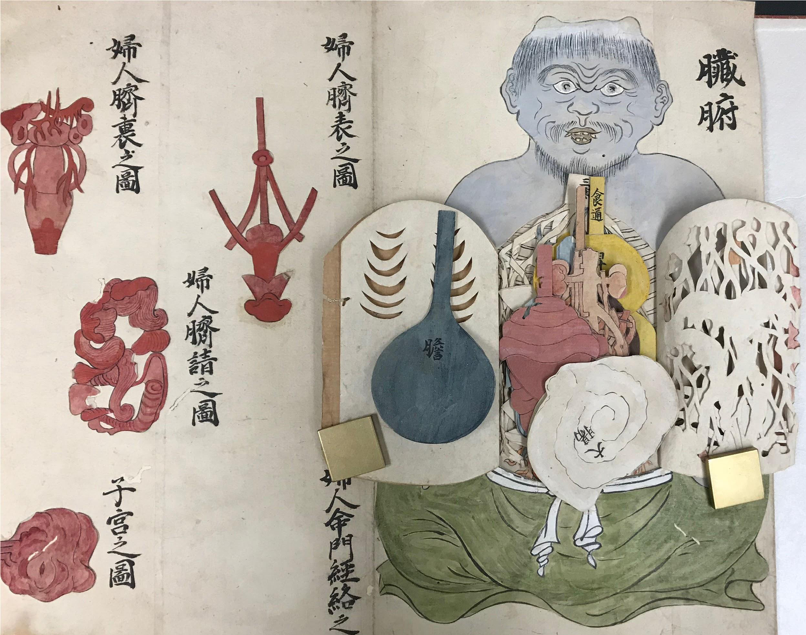

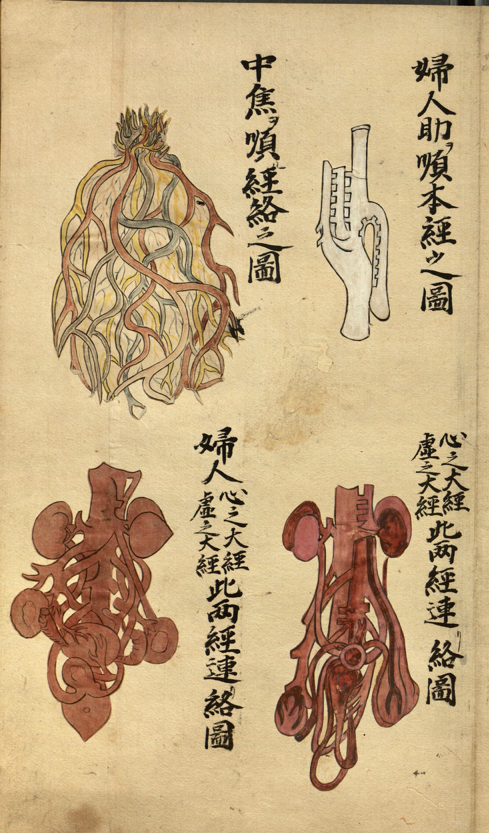

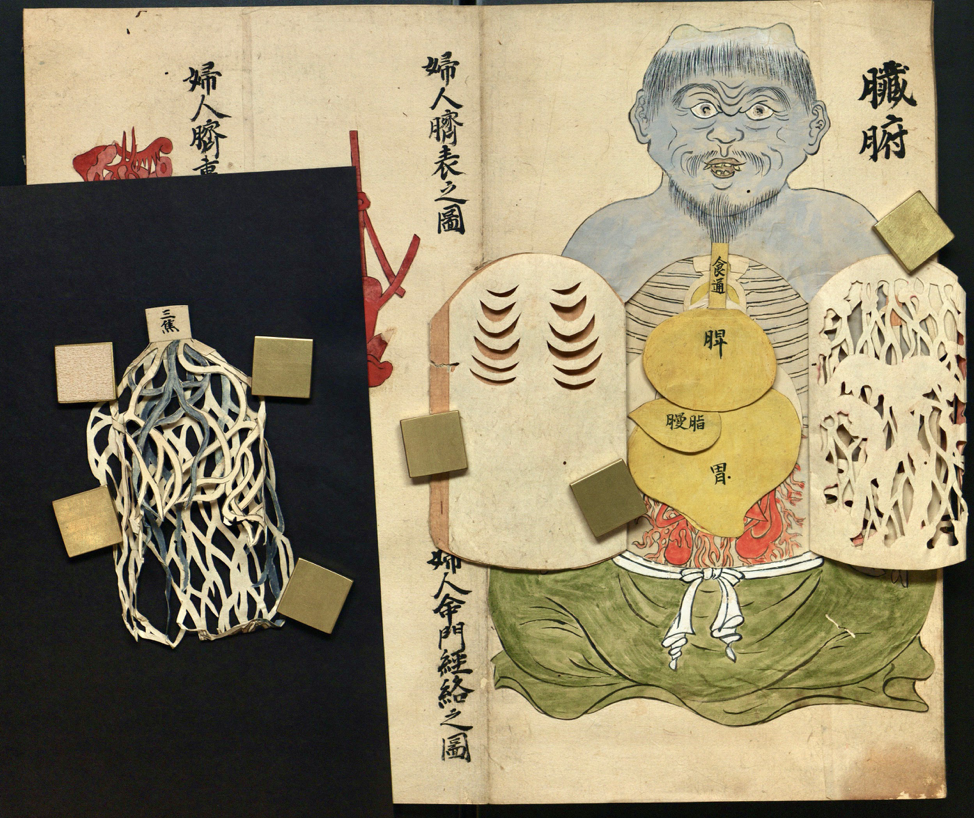

As is typical in East Asian texts, the manuscript opens and reads right to left. The work is composed of several types of paper ranging from thin rice paper to thicker sturdier cardstock-like paper. Composed of sixteen pages, the hand-colored manuscript is constructed using an accordion fold binding. The text provides a description of the major systems of the body ranging from the muscular and circulatory systems to discrete organs. Opening with a visual key that connects systems of the body to the colors red, blue, black, white, and yellow, the reader is cued to anticipate these colors throughout the work. Following this opening color key, the next two pages yield the first set of figures composed of flaps: a male figure depicted and anatomized from anterior and posterior views. The manuscript has thirteen flap anatomies, ranging from whole human figures of men, women, and a blue demon, and several flap anatomies of individual organs or systems, such as the eye, nose, and top of the head and brain.

In total, there are nearly 100 flaps in the volume, often double sided, and all hand-colored, cut and labeled. In addition to these flap anatomies, there are twenty-nine flat images of other body parts, systems, and events, such as the heart, pelvis, and fetuses in utero.

Book Technologies and Medical Theories

Although the translated and printed copy of Remmelin’s flap anatomy published in 1772 mostly appears to have maintained Western theories of human anatomy and medicine, the Wangensteen’s manuscript flap anatomy presents a view of the body that is securely based on traditional Chinese medical theory. For example, the ways the organs are depicted, both in terms of shape and color, are consistent with Chinese medical theory in the early modern period in Japan.

The flap anatomy of the pregnant woman has flaps which depict ten months of gestation, typical of Chinese medicine, rather than the nine months typical of Western medicine.

The volume also features organ systems that do not have corollaries in Western medicine. For example, the image on the top left of page nine shows the “middle warmer of the triple warmer [or, burner] (sanjiao).” It’s notable that one of the images of the triple warmer is located in the flap anatomy of the demon.

According to Wayne Soon, PhD, “The triple burner is a special concept in TCM, and there is no corresponding organ in western medicine. Suggestions have been made that the triple burner’s function may be related to the pancreas and metabolism in the body, but no clear conclusion has been reached as to the nature of this organ. The triple burner is actually a collective term for the upper, middle and lower burner. The Chinese word “triple burner” actually means “three parts which burn or scorch.”… The triple burner’s functions relate to the activities of qi and the movement of water. The functions of the three burners were summarized in the Huang Di Nei Jing (The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine) as follows: “The upper burner acts like a mist. The middle burner acts like foam. The lower burner acts like a swamp.”

This Japanese manuscript flap anatomy seems uniquely situated to expand scholarly conversations about knowledge transfer between East Asia and Europe to include the ways European book technologies themselves may have affected the ways Chinese medical theory was conceptualized three-dimensionally and taught.

Conclusions

Since we do not read Chinese or Japanese, or have deep knowledge of medical practice and theory in early modern East Asia, this blog post should be understood as more of a call for further research by experts than anything else. Other materials in the Wangensteen’s collection certainly seem to contextualize the information presented in this manuscript. Many other anatomical texts use the same organ forms and colors as this manuscript and acupuncture broadsheets from the late 17th century show the same colors and channel systems that appear on the first few pages of the flap anatomy, as described above.

The Wangensteen’s collection of European flap anatomies similarly contextualize this document, highlighting how book technologies were transferred and adopted in different geographic contexts during this period. This past year the Wangensteen Library has focused on early modern texts with moveable parts in conjunction with the research workshop Making & Knowing: Histories of Premodern Books & Print. The project is sponsored by the Consortium for the Study of the Premodern World at the University of Minnesota. This workshop employs an integrated approach to studying the materiality of prints and texts. Participants learn the fundamentals of codicology, and have the opportunity to analyze the materiality of books in order to fully explore the complex and multifaceted nature of early modern printed materials. This workshop also engages the mediational qualities of print including the ways in which printed images circulate, request viewer interaction, and translate visual information.

For a Digital Walk-Through of the First Set of Flaps of the Anterior Figure:

https://dash.umn.edu/portfolio/japanese-interactive-flap-anatomies/

For Further Reading:

Clements, Rebekah. A Cultural History of Translation in Early Modern Japan. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Joby, Christopher. “Dutch in Eighteenth-Century Japan.” Dutch Crossing, October 7, 2017, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1383643.

Johnson, Hiroko. Western Influences on Japanese Art: The Akita Ranga Art School and Foreign Books. Amsterdam: Hotei, 2005.

Leslie, Charles, and Allan Young. “Between Mind and Eye: Japanese Anatomy in the Eighteenth Century.” In Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge, edited by Charles Leslie and Allan Young, 21–43. University of California Press, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520073173.003.0002.

Sakula, Alex. “Kaitai Shinsho: The Historic Japanese Translation of a Dutch Anatomical Text.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 78, no. 7 (July 1985): 582–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107688507800712.

Schmidt, Suzanne Kathleen Karr. Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance. Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History, volume 270. Leiden Boston: Brill, 2018.

Screech, Timon. Obtaining Images: Art, Production and Display in Edo Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2012.

Tubbs, R. Shane, Marios Loukas, David Kato, Mohammad R. Ardalan, Mohammadali M. Shoja, and Aaron A. Cohen Gadol. “The Evolution of the Study of Anatomy in Japan.” Clinical Anatomy 22, no. 4 (May 2009): 425–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.20781.

Social Media: