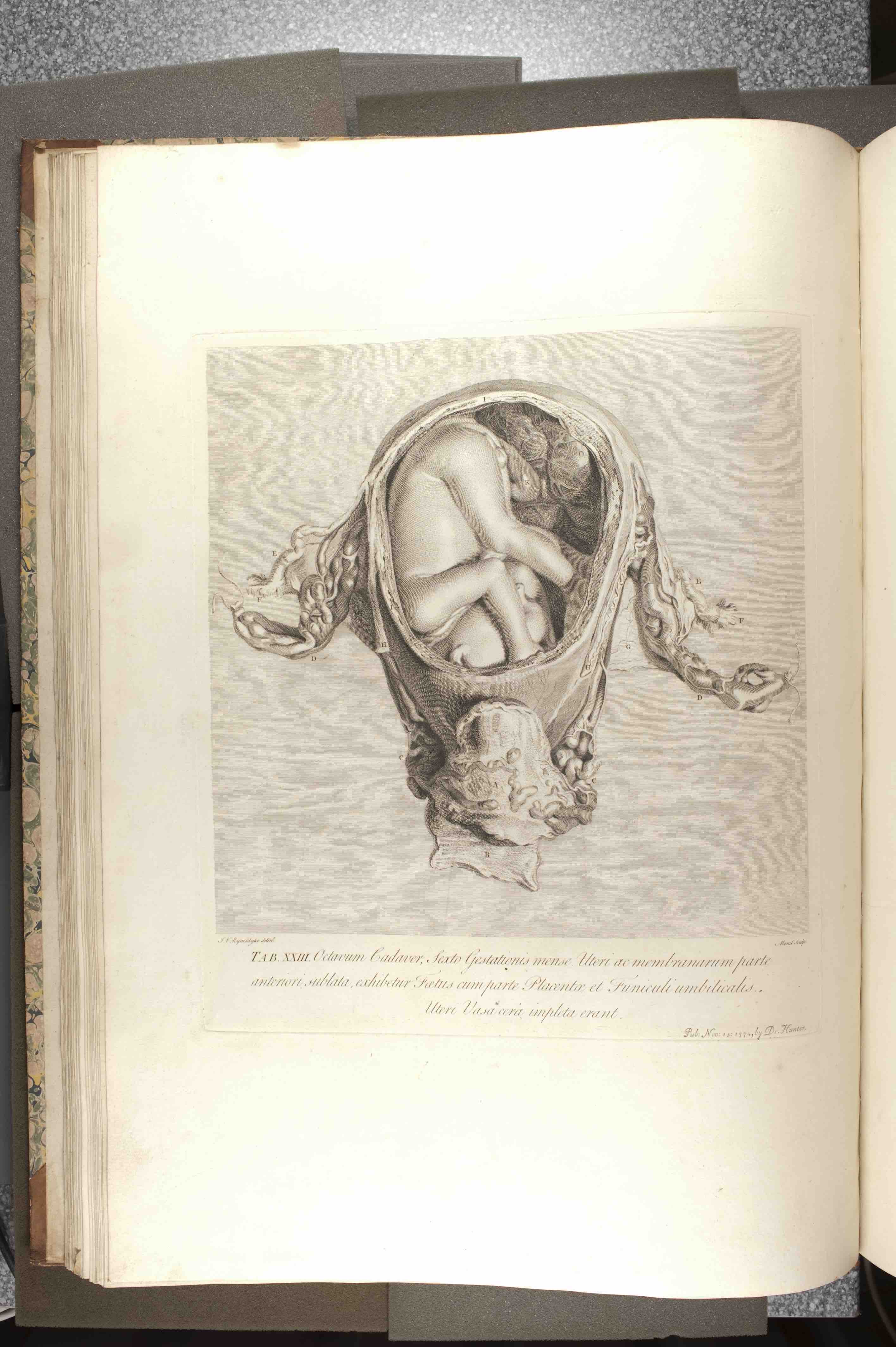

When The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures was published over 240 years ago, it revolutionised the study of the pregnant body. For the first time physicians could see a realistic depiction of a foetus in utero as the images in the book made their way around specialist circles.

The author and initiator was William Hunter FRS (1718-1783), a Scottish physician interested in the challenges of teaching anatomy and obstetrics. In his anatomy theatre in Great Windmill Street, Soho, he taught a generation of surgeons, and his books taught even more. The Anatomy… was illustrated with engravings by Jan van Rymsdyk (c. 1730-c. 1790) and other unknown artists, with a visual model of Leonardo da Vinci, conserved at the time in the Royal Collection at Windsor. For this, the art historian Kenneth Clark saw him as responsible for the eighteenth-century rediscovery of Leonardo’s drawings in Britain. Hunter also had connections to the art world via his anatomy teaching at the Royal Academy of Arts. It is this combination of art, medicine, and print culture that made The Anatomy… so unlike anything that had existed in the field before.

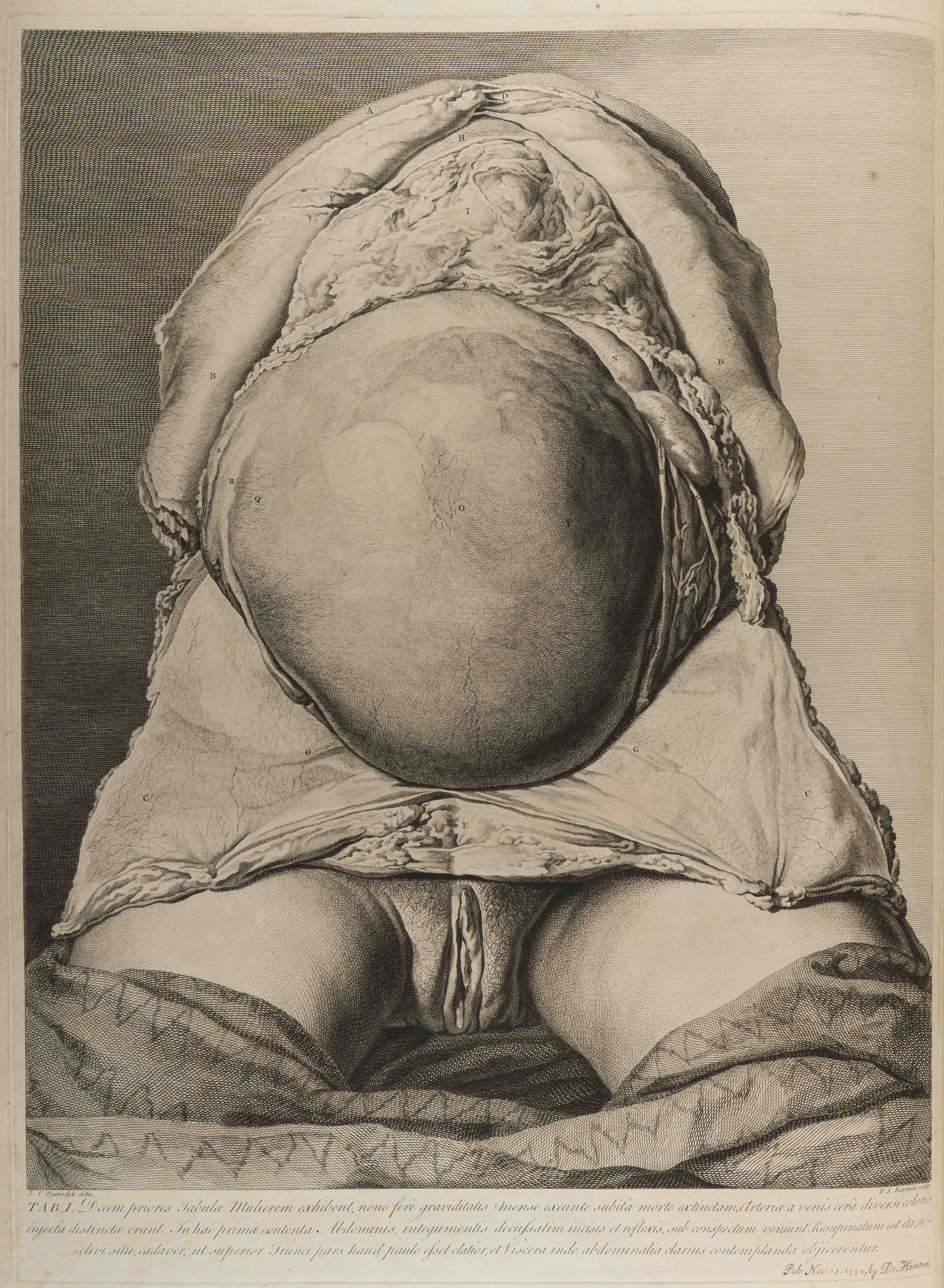

Hunter made his observations during his work dissecting pregnant bodies from 1740s to 1770s. A 2010 study of Hunter’s work claims that he and his collaborators had murdered a dozen pregnant women in order to have a continuous flow of bodies at hand. Hunter also had a steady supply of corpses from the execution squad, smugglers and criminals. We should keep this in mind when we look at these plates, violent in their depiction of cut stump bodies, frozen in time. It is a reminder of the long patriarchal past of obstetrics.

The book is dedicated to the King of England, George III (at the time Hunter was the Physician to Queen Charlotte). The preface details his aims in providing a visual and objective account of the pregnant body as observed in the laboratory. Earlier portrayals had shown women moving or alive, Hunter wanted them dead and dissected for accuracy. The author is not sentimental, writing neither about the virtues of motherhood or life itself. Similarly, the artists were instructed to draw from dissections directly, not from memory.

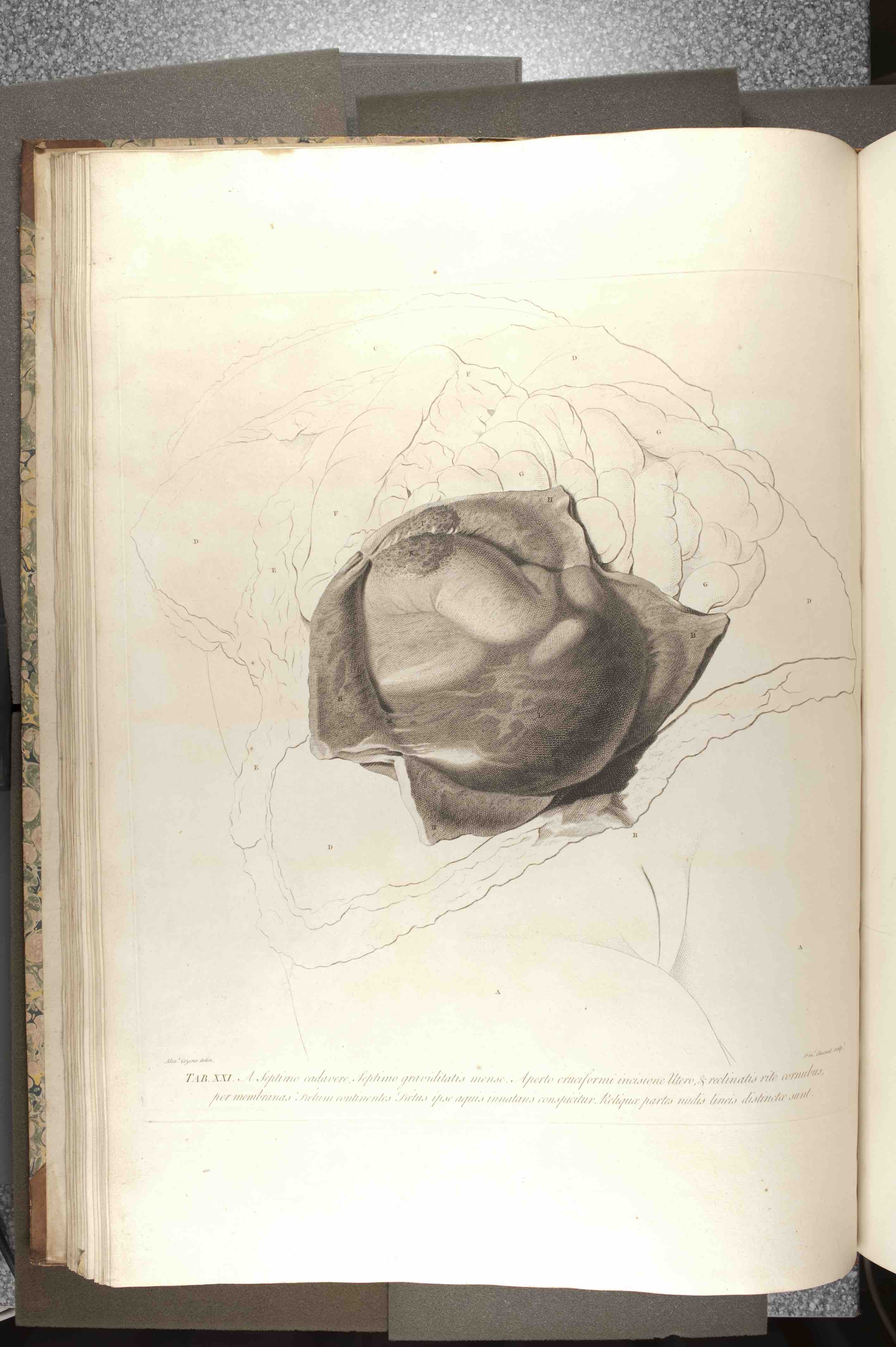

The illustrations themselves are astonishing and rare visual examples of the pregnant body. Earlier depictions of pregnancy did exist prior to The Anatomy…, but these were far and few between, and based on a radically different visual language and methodology of the body. Earlier illustrators had not based their accounts on the three-dimensional, real body, as available only through dead bodies and careful dissection. The idea of looking at or dissecting a pregnant body was especially rare, due to the lack of specimens available and the taboos connected to the use of these at the time (in fact, one could argue that Hunter worked at the only time in medicine when such a methodology would have been considered in any way ethical). Earlier artists would draw on their imagination and observation of living and moving pregnant bodies, and could not realistically depict the internal status of the foetus. Rather they depicted it from the outside-in. Hunter’s radical idea to depict the pregnant belly from inside-out, therefore visually as well as medically transformed the field of obstetrics. The realistic and three-dimensional depiction of the uterus thus put a stop to the prior imaginings and creative and varied depictions of pregnancy. The careful shadowing and attention to detail, in the style of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings, would later be described as beautiful and delicate by art and science historians, but it is important to remember that the style and method were chosen for practical medical reasons, and not for the sake of beauty.

Hunter correctly spotted a gap in the medical literature at the time, and filled this with his dead women, foetuses and descriptions of plates. He ordered the plates in reverse chronological order, from subjects who died at nine months gestation down to five weeks gestation. Alphabetical labels on tissues and organs were intended to help the student understand the depiction of this realistic looking, but never-before seen body.

The original edition is a large atlas of copper plates, ca. 62 x 45 cm in size. This made it a bulky and rare item. A specialist company in Birmingham made a limited number, one of the most expensive items in print at the time. Because of this, the item was not easily accessible, and the work mainly circulated in the medical community (minus the field of midwifery, which was largely female and not professionalised in the same way at the time); - until revisited by historians and feminist historians of science in the 20th century, and digitised several times in the 21st century.

The reception of the work was, then as now, mixed, with some arguing that knowledge of female anatomy was unnecessary in the work of midwives and surgeons. Most readers of The Anatomy… championed Hunter, and he subsequently became one of the most important figures in medical history. The work has been said to have helped a generation of obstetricians to better understand childbirth, abortion and pregnancy, but it has also been seen as a work of art in itself.

Further reading

Andrews, Henry Russell. “William Hunter and His Work in Midwifery.” British Medical Journal 1 (1915): 277-82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2301755/pdf/brmedj07218-0001.pdf (Accessed January 7, 2016)

Drife, James. “The Start of Life: A History of Obstetrics.” Postgraduate Medical Journal 78 (2002): 311-5. http://pmj.bmj.com/content/78/919/311.full.html (Accessed January 7, 2016).

Moore, Wendy. The Knife Man: The Extraordinary Life and Times of John Hunter, Father of Modern Surgery. New York: Broadway Books, 2005.

Wagoner, Nevada, “Anatomia Uteri Humani Gravidi Tabulis Illustrata (The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures) (1774), by William Hunter”. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2017-04-13). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/11475.

For a discussion of Hunter and his colleagues as murderers, see the debate around this article: Shelton, Don C., “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (February 2010) 103:2:, pp. 46-50.

Fully digitised copy available here: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/2491060R.

See also, for reference, here: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dreamanatomy/da_gallery.html.