On May 20th 1511, the Venetian publisher Giovanni da Tridentino, also known as Tacuino, presented M. Vitruvius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula ut iam legi et intelligi possit: the first illustrated edition of the De architectura by Vitruvius. The editor of this work was the Veronese friar Giovanni Giocondo, one of the most multifaceted minds of his time: architect and humanist, he was known for his epigraphic and philological interests, but also worked as an engineer (first in Naples and then in France, where he participated to the reconstruction of the bridge of Notre Dame), and was at the service of the Republic of Venice as an expert in hydraulics and fortifications.

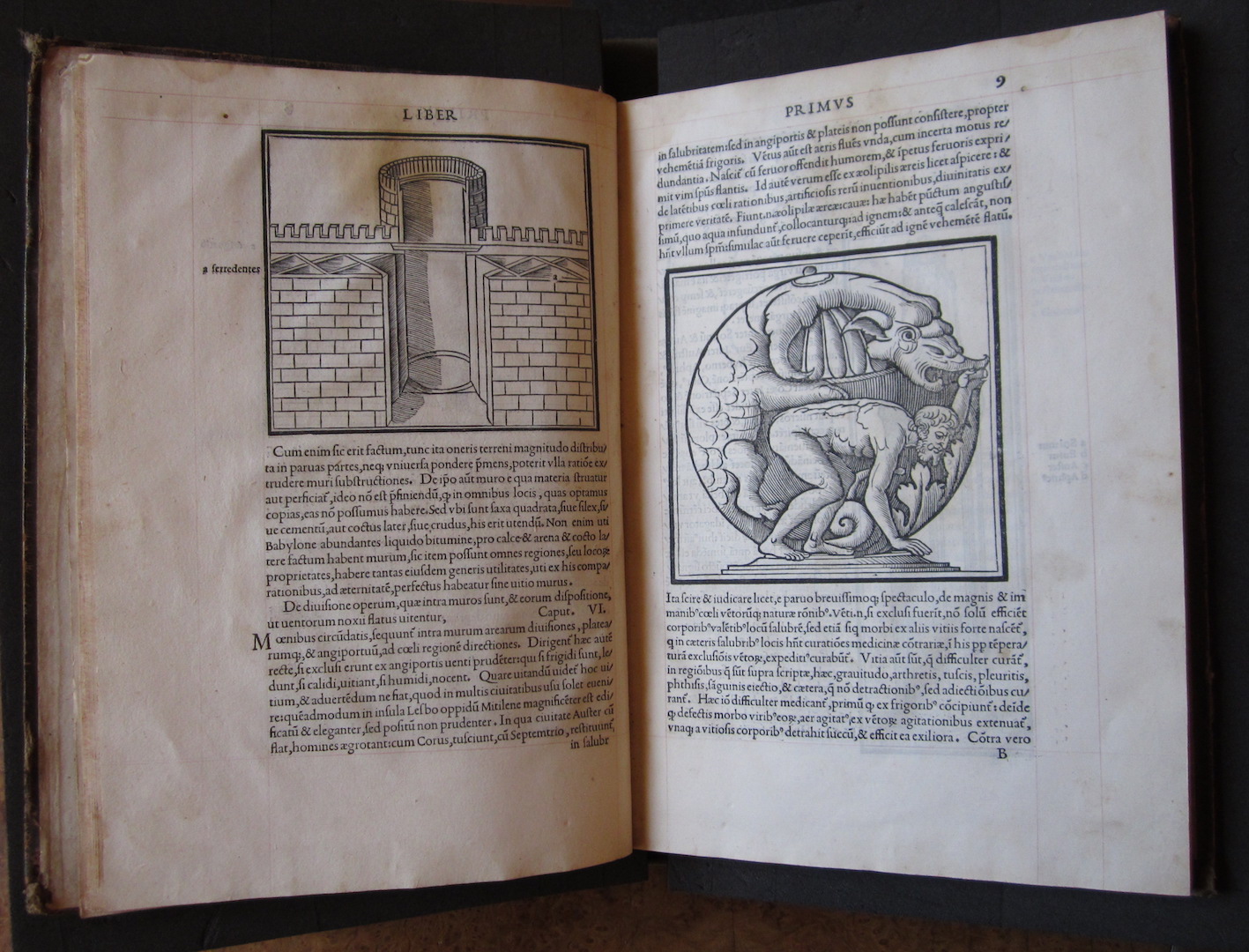

Giocondo’s skills developed across many fields of study, allowing him to approach a particularly obscure text such as the De architectura, defined by a thematic heterogeneity that very much characterises the consequent implications on the language it adopts. The friar presented a philologically amended edition, illustrated by a rich xylographic apparatus: 136 woodcuts distributed throughout all ten books, and the addition of an index to facilitate the reader in understanding the text, allowing him to approach it from an operative point of view.

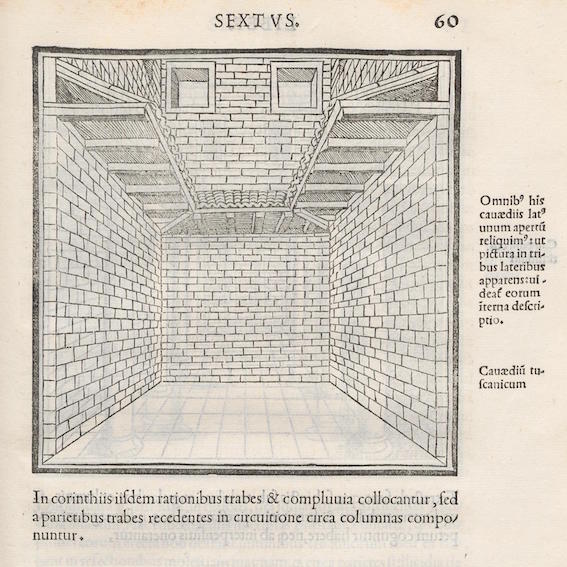

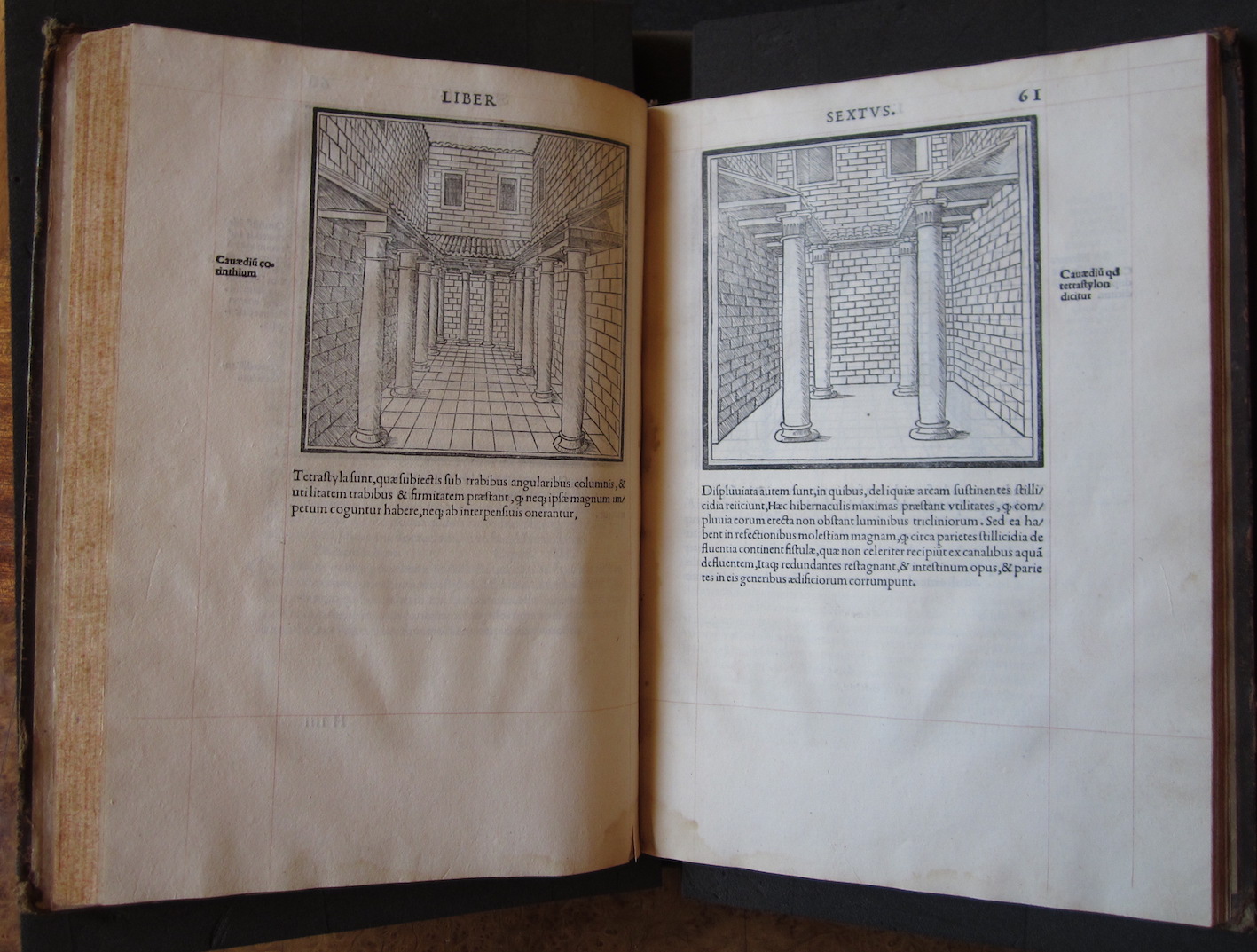

Giocondo had to deal not only with issues of interpretation connected with the actual themes, but also with the choice of the best ways of representing and illustrating them. For example, with regard to the representation of the cavaedium - for which he offers a rendition that is commonly recognized as littered with errors of interpretation - Giocondo correctly uses perspective representation, which he managed by removing one wall in order to make the other three visible, as explained in the text (f. 60r): “omnibus his cavaedis latus unum apertum reliquimus ut pictura in tribus lateribus apparens videatur eorum interna descriptio”.

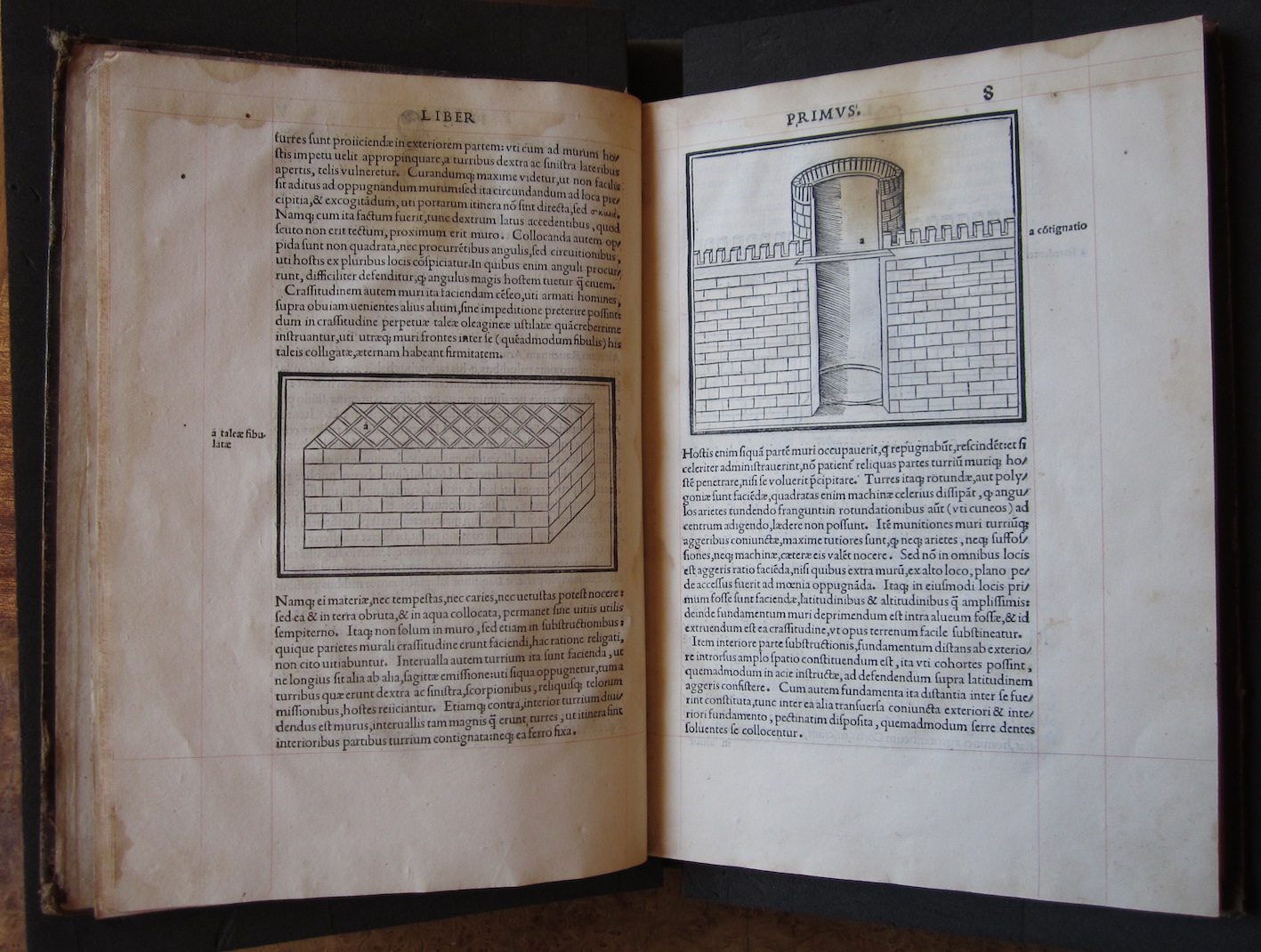

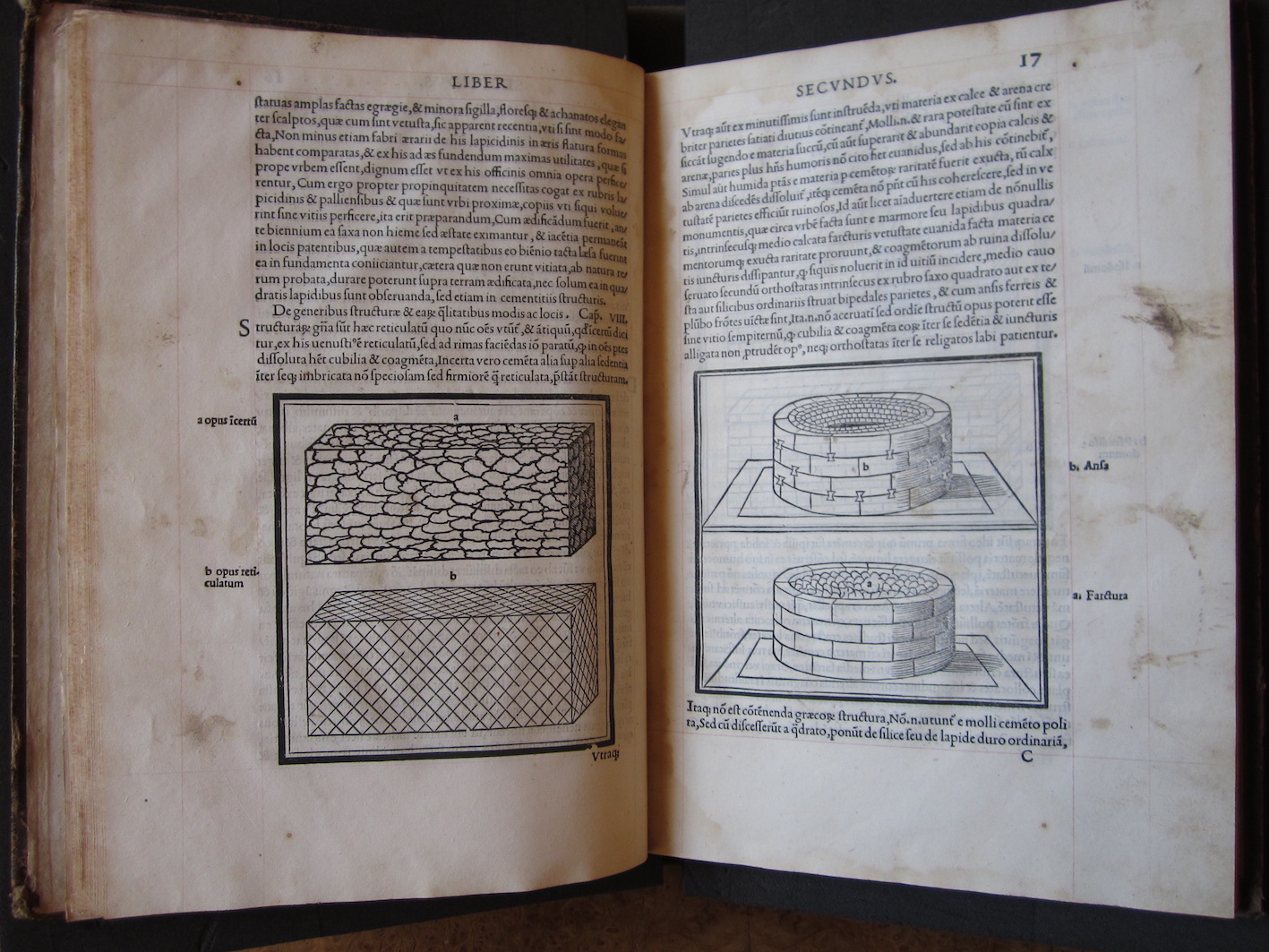

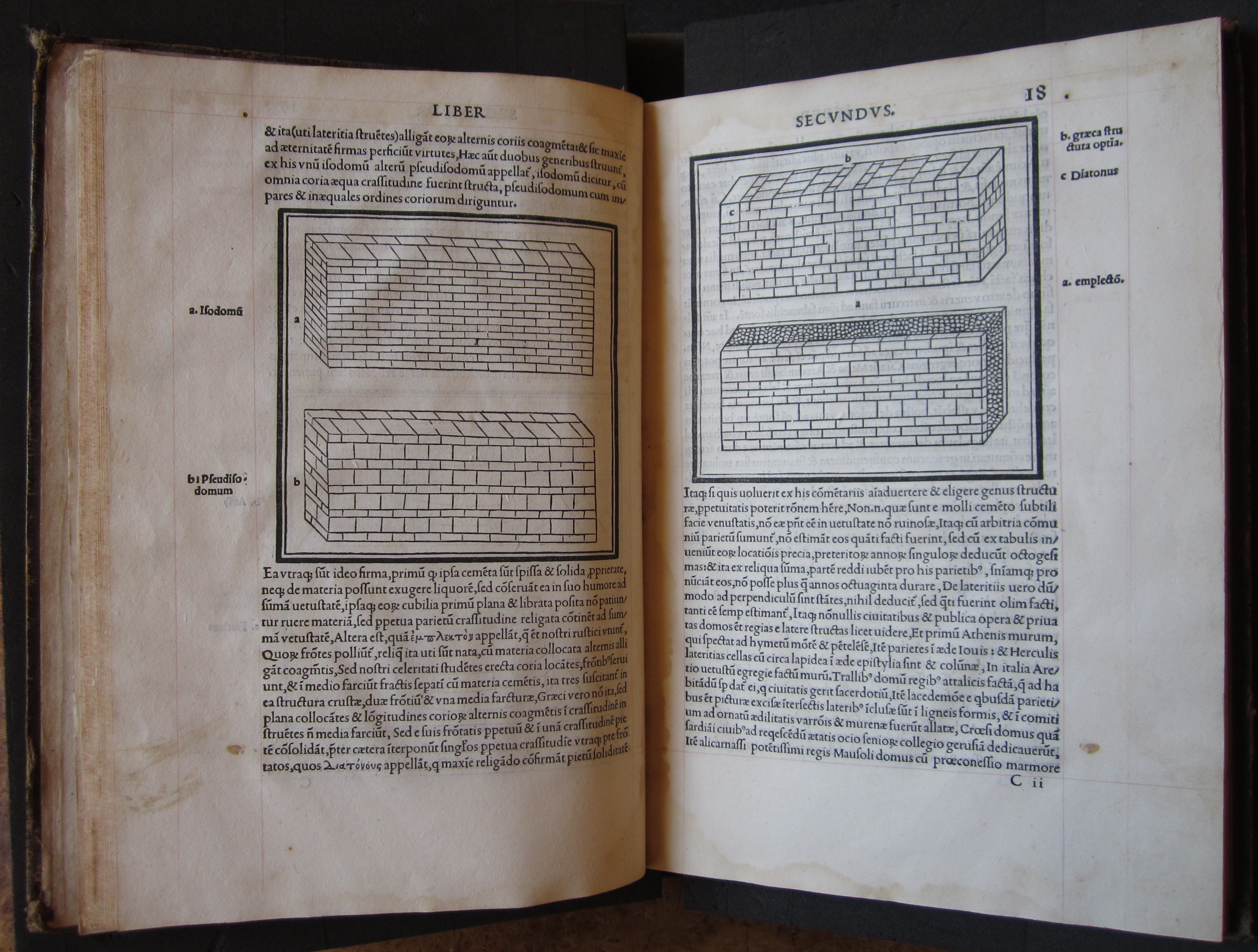

Giocondo’s intention to open up the Vitruvian text to an ‘operational’ public is translated into representations that reveal a construction-oriented way of thinking. This is the case of the pages related to the different types of masonry (ff. 7v, 8v, 16v, 17r, 17v, 18r): Giocondo expresses the tight relationship between external surface and internal structure (through axonometric representation), also revealing his own understanding of the ancient model and of the (uncommon) construction issue, as emerges from the comparison with the subsequent 1521 representations by Cesare Cesariano. On this specific theme, the woodcut on f. 14v is particularly interesting, since it illustrates the different types of bricks. Although two-dimensional, the representation tends toward a three-dimensional grip on the issue: Giocondo shows how to obtain solid brickwork by superimposing one row of the right-side column to the corresponding one on the left.

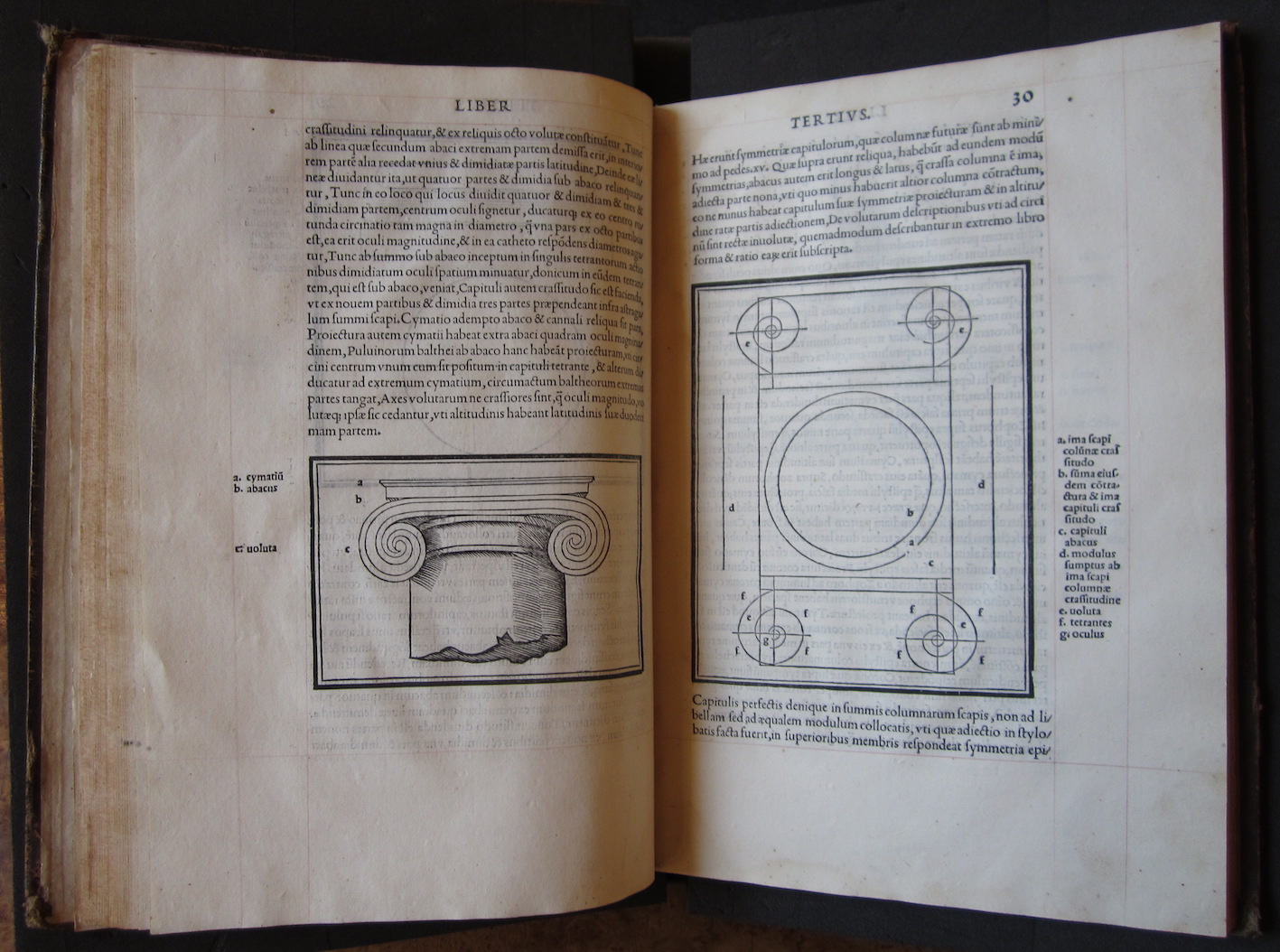

With respect to the issue of translating a construction operation into an image, the method for illustrating an Ionic volute (Vitr., III) on f. 30r, one of the most complex Vitruvian issues, is particularly interesting. Giocondo, although working with an incomplete text, provides an exact term of graphic comparison to it, through a schematic yet exhaustive representation: the friar proposes a sort of ‘unraveled’ flattened depiction of the Ionic capital, showcasing the upper part and breadth of the abacus, as well as the upper and lower diameters and lateral volutes, all at the same time, thus providing all the necessary information for a three-dimensional visualization of the capital and its construction scheme.

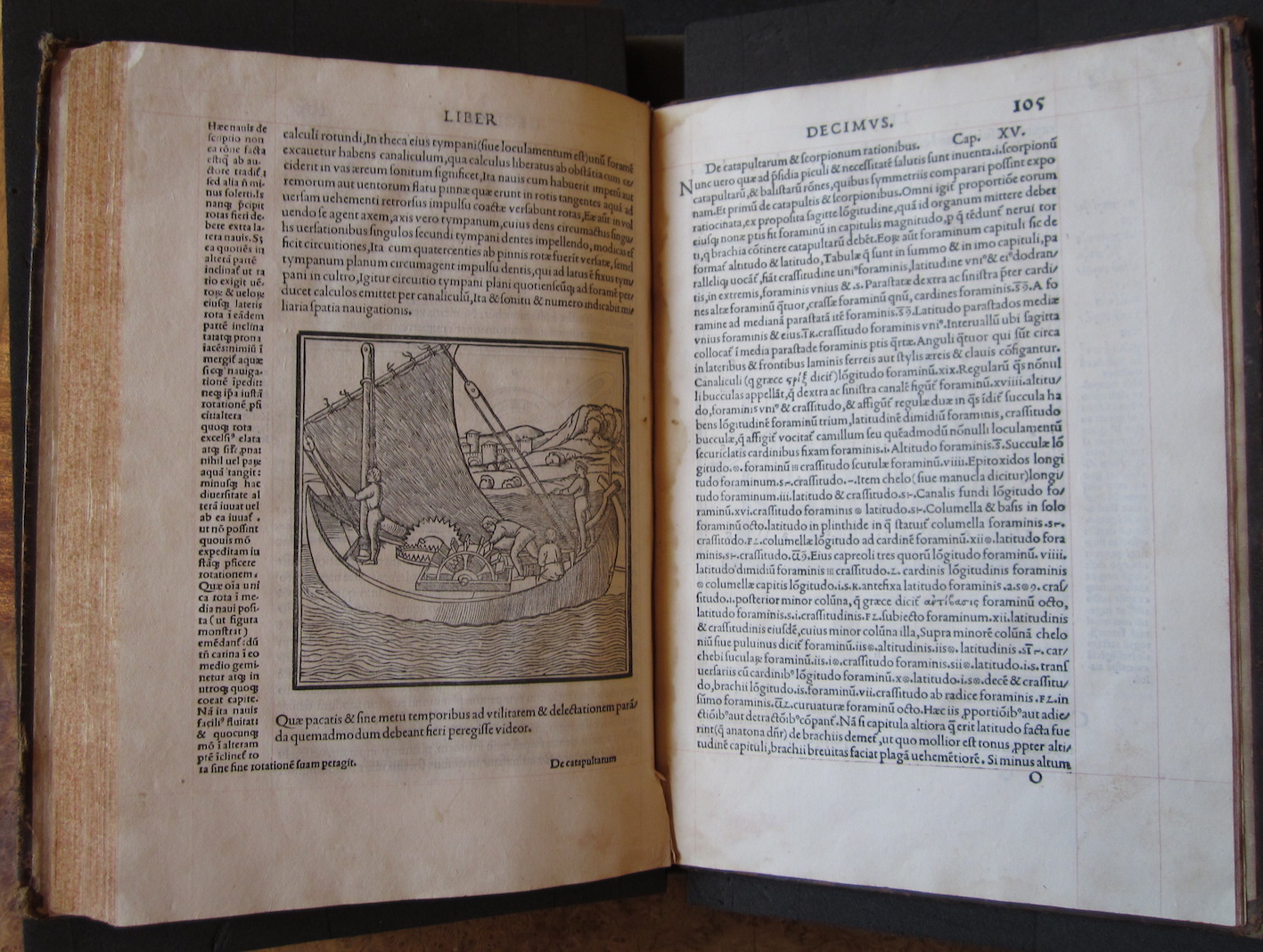

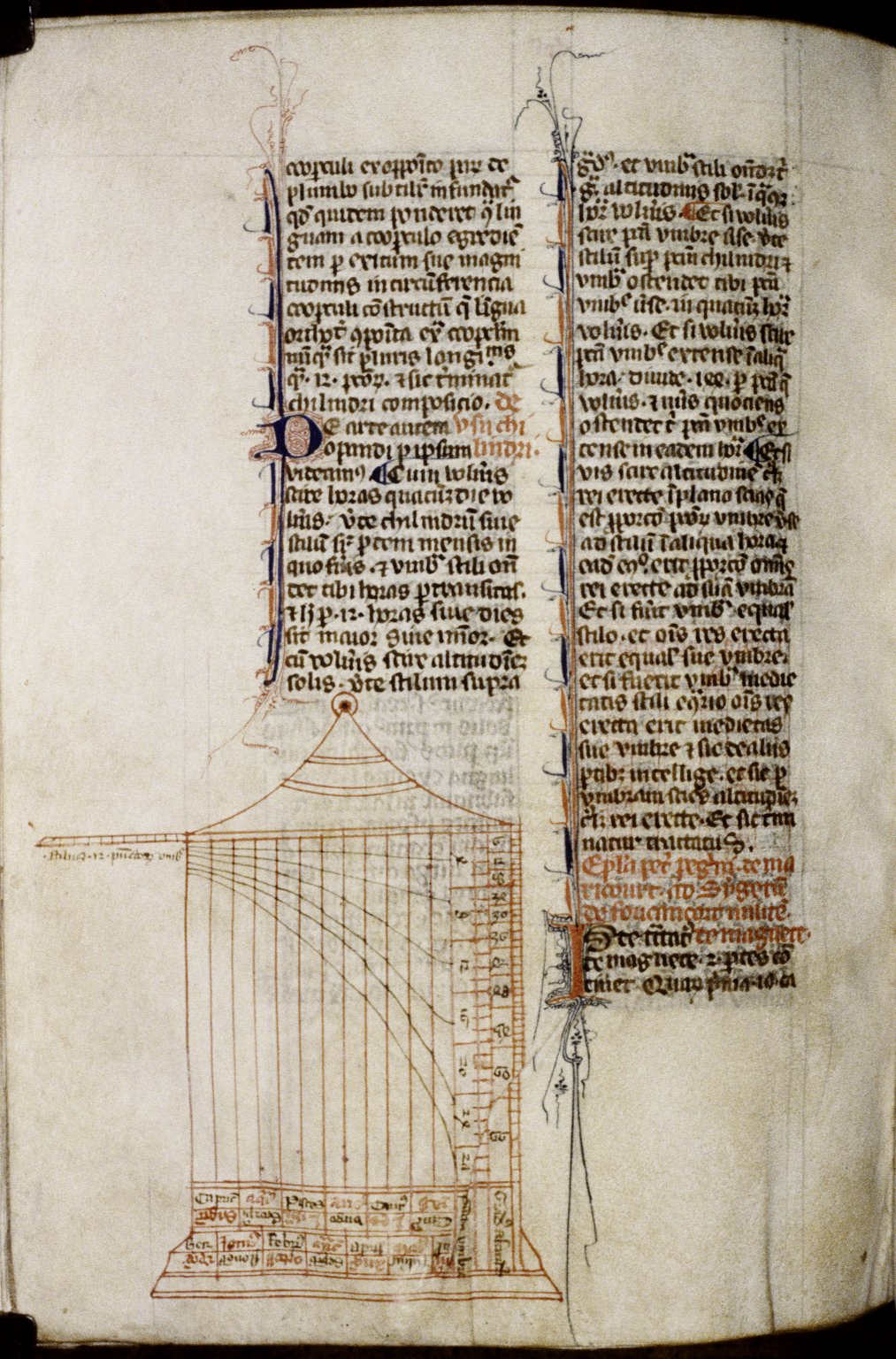

The 1511 edition is also noted for its contribution to the understanding of books VIII, IX, X of the De architectura, on issues related to hydraulics (gnomonice and machinatio), which were contiguous to the interests and practices of the friar, who was hired as “Consili X maximus architectus” for his reputation as an expert on water issues. Giocondo did not lack in proposing solutions that differed from the ones outlined by Vitruvius, perfecting them during his own activity, and even sometimes openly criticizing the ancient text, as in the case of the marine odometer (f. 104v).

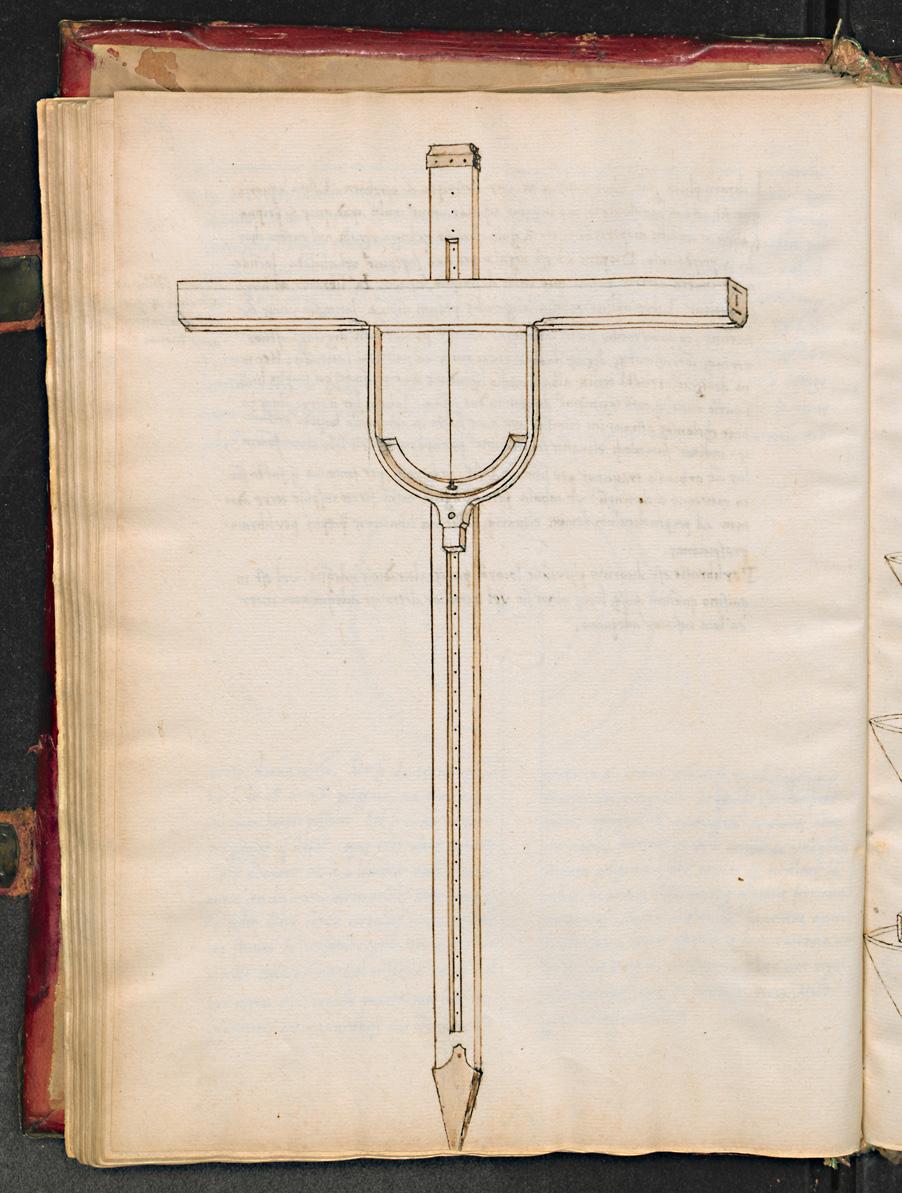

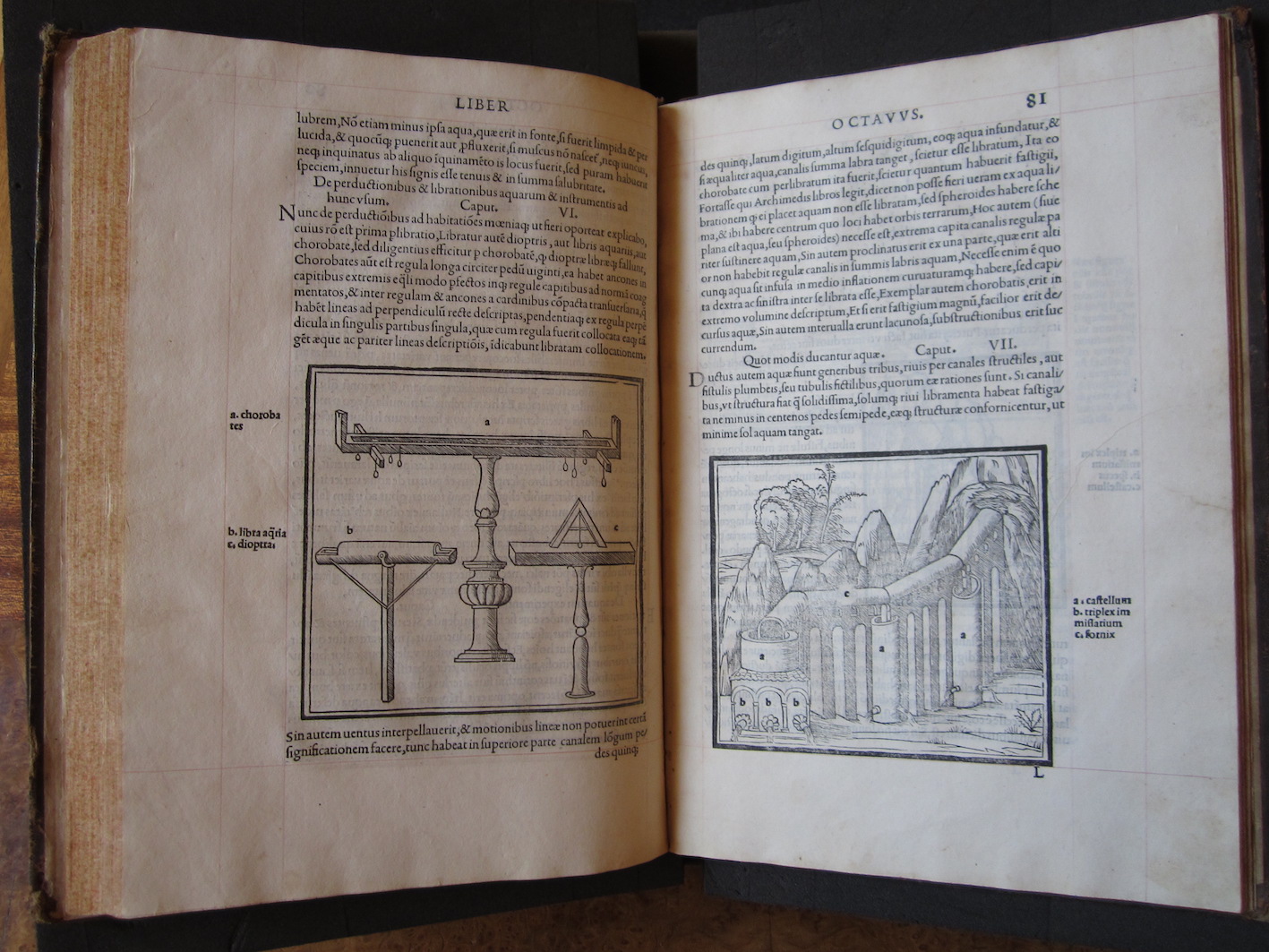

In book VIII (Vitr. VIII, 5, 1), Vitruvius recalls three instruments for water leveling: diopters, water levels, and chorobate (a tool similar to a modern spirit level), providing only the latter with a brief description that could be compared with a drawing at the end of the book. Chorobate, similarly to libra aquaria, is a Vitruvian hapax legomenon. However, Giocondo, inventor of leveling instruments like the jocunda (mentioned in the manuscript Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut.29.43), did not resist offering a new graphic proposal to the reader, representing instruments he perfected himself, parting from the Vitruvian canon (like, for instance, on f. 80v).

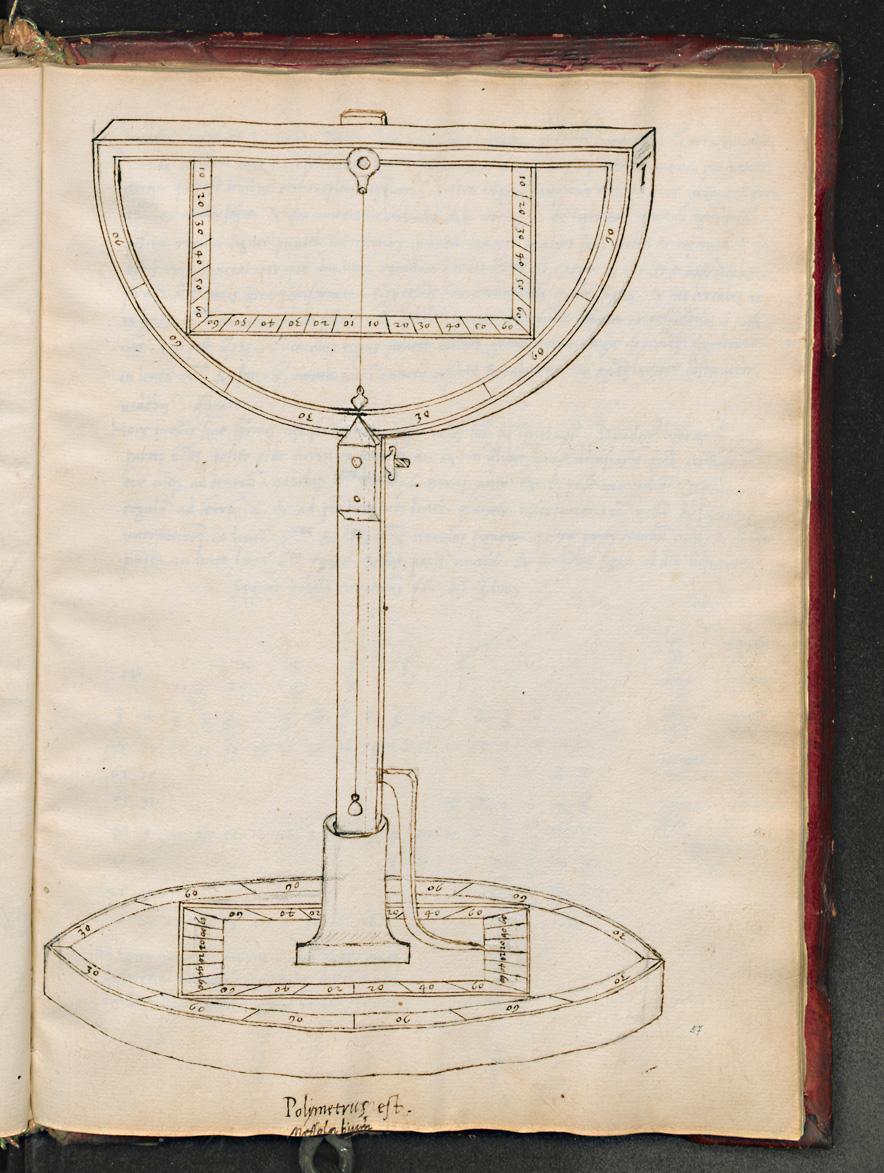

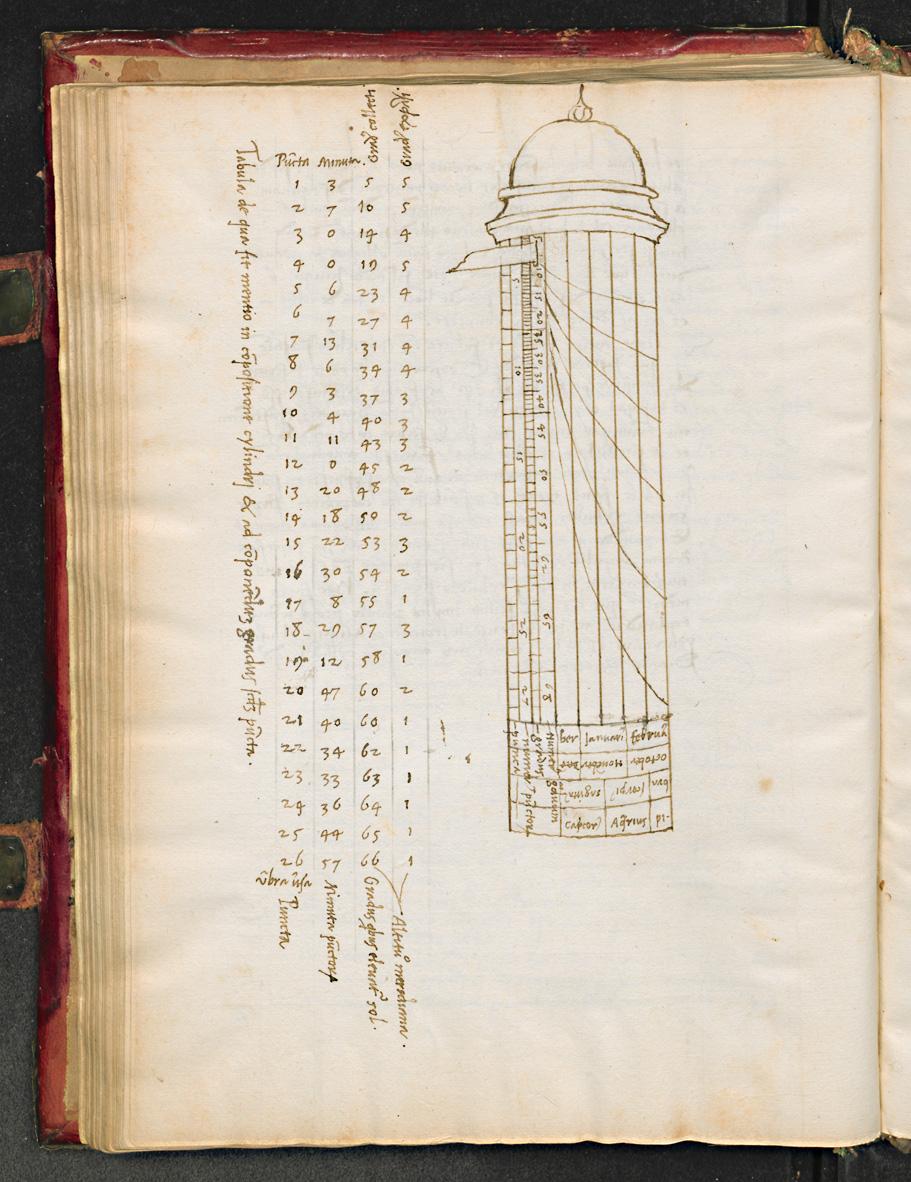

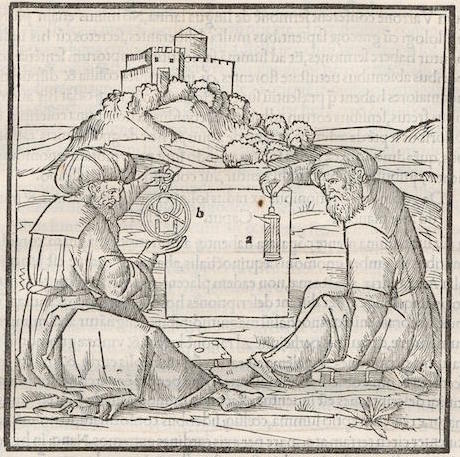

In book IX, at f. 86r (dealing with the Delian problem of doubling the cube), Giocondo represents Archytas of Taranto and Eratosthenes of Cyrene holding two instruments, called cylindrus (a) and mesolabium (b). These are an astrolabe (an astronomical measuring instrument and a topographic survey instrument) and a sundial, called cylindrus. The image reveals Giocondo’s attention to ancient mathematics, to which he dedicates much time in several of his manuscripts: it is known that Giocondo was familiar with Jean Fusoris’ treatise on the astrolabe. The issue is certainly not marginal in the friar’s interests and therefore the non-achievement of a correct graphic restitution is suspect, to say the least.

Although free of scientific intent, the graphic proposal by Giocondo could hold a reflection on the angular momentum that binds proportional triangles, which is detectable with an astrolabe: the geometric rules, on which the instruments for detection are based, refer to the same theory of proportions and similar figures on which the resolution of the same Delian problem is based.

In the De architectura published in Florence in 1513 by Filippo Giunti and edited once again by Giocondo, the system indicated as cylindrus (f. 145v) is comparable to some Da Vinci sketches for the determination of the square equivalent of a given rectilinear figure (Cod. Forster I, f. 32): a rectangle formed by the juxtaposition of two equal cubes, based on the method mentioned in the fourteenth proposition of the second book of Euclid. If this were the case, Giocondo (perhaps aware of Da Vinci’s studies through Pacioli’s mediation) would have opted for a method that according to Da Vinci himself constitutes a simplification of the “faticoso negozio” of the ancients.

The significant aspect that emerges from this brief examination is Giocondo’s attitude and propensity to update the ancient description in order to make it an operative tool for his contemporaries.

Further reading

Entry by Pierre Gros on the 1511 edition for Architectura.

Entry by Frédérique Lemerle on the 1513 edition for Architectura.

Pierre Gros, Pier Nicola Pagliara (eds), Giovanni Giocondo: umanista, architetto e antiquario, Vicenza: Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio, 2014.

Francesca Salatin, “‘In alcune figure errò Giocondo’: note su alcune xilografie del Vitruvio del 1511”, in Paolo Clini (ed.), Vitruvio e l’archeologia, Venice: Marsilio, 2014, 173-91.

Adolfo Tura, “Codici di matematica di Fra Giocondo”, Bibliothèque d’humanisme et renaissance 61 (1999): 701-11.

Lucia Ciapponi, “Fra Giocondo da Verona and his edition of Vitruvius”, in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 47 (1984): 72-90.

Fully digitised copy of the 1511 edition from the Centre d’Études Supérieures de la Renaissance, Tours is available here.

Fully digitised copy of the 1513 edition from the Bibliothek Werner Oechslin is available here.

The manuscript Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut.29.43 is fully digitised and accessible online via Teca Digitale.

The manuscript Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, MS Ashmole 1522 is partially digitised and accessible online via LUNA.