Nowadays, the habit of decorating the dining table to impress guests on special occasions is widespread, and happily thrives on social media channels such as Instagram and Facebook, together with professional and amatorial food photography. At first sight, it does not seem a great deal: it is all about choosing the right colours and creating the desired atmosphere, ensuring tablecloths, centrepieces, napkins and crockery all become part of an harmonious ensemble of colours and shapes. The most ambitious hosts might even try their hand at napkin folding, to add an extra touch to the table and elicit amazed comments from their commensals. Such practice has become so fashionable, that one can choose from a variety of different manuals, each featuring detailed instructions enriched with diagrams and pictures.

However, whilst many are familiar with the origins of origami – the closely-related Japanese art of folding paper to create natural and animal shapes – only few are aware that the practice of napkin folding first developed at the Renaissance courts in the North-East of Italy, where it made possible to craft marvellous centrepieces known as trionfi da tavola (‘table triumphs’), often embellished with decorative elements made of glass, ceramics or even sugar. Besides having a decorative function, such complex centrepieces also fulfilled a subtler purpose: in fact, during the banquet guests were expected to identify and comment upon the hidden symbolic meaning of the figure reproduced by the folded centrepiece, which was thus understood as a conversational piece in its own right, just as the elegantly-decorated maiolica dishes so ubiquitous on Renaissance tables.

Although largely known and practised throughout the sixteenth century – when table etiquette began to grow consistently elaborate and a significant range of new manners was introduced – it is generally understood that napkin folding only became a techne in its true sense in 1629, when Mattia Giegher (the Italianised name of the German Matthias Jäger), yielded the first graphic and written description of the art in his popular Trattato delle piegature, part of a major literary work entitled Li tre trattati and published in Padua. Judging from the information retrievable in his books, it seems likely that the young Matthias – a native of Moosburg (Bavaria) – decided, shortly before the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, to begin a new life in Italy, where he gradually built an expertise in food carving, stewarding and napkin folding – all subjects he later taught at the University of Padua.

As the title suggests, three separate treatises form the body of Giegher’s Li tre trattati, a comprehensive recollection of his lifetime experience as trinciante (‘food carver’) and table server: Lo scalco, already published in 1623, Il trinciante, previously published in 1621, and the aforementioned treatise devoted to the folding of starched napkins. The latter, dedicated to the councillor Burcardo Ranzovio (probably Burkhardt Rantzau from Sassendorf), was then considerably expanded and translated into German by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer in 1657, becoming the primary source for many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century treatises on napkin folding.

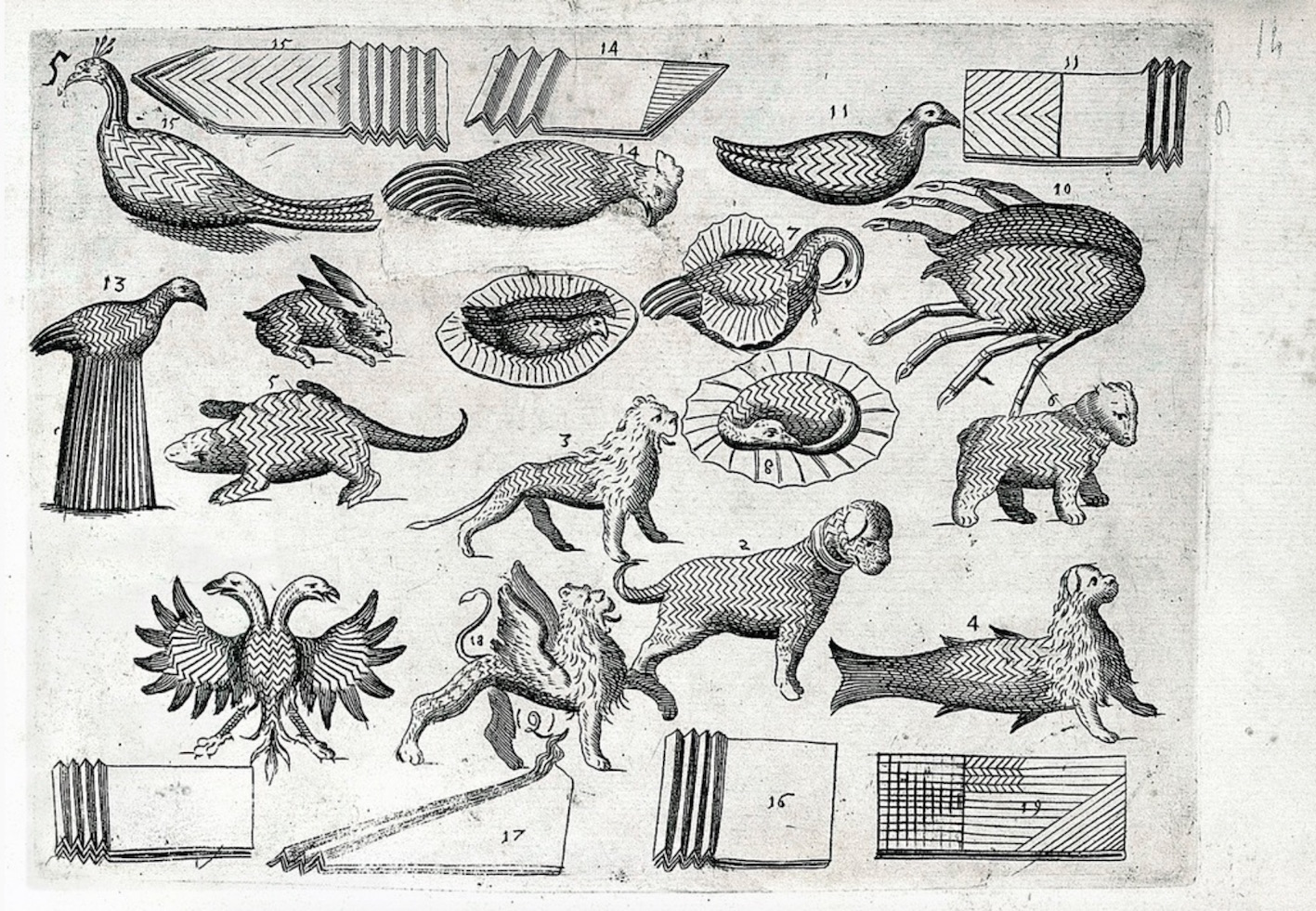

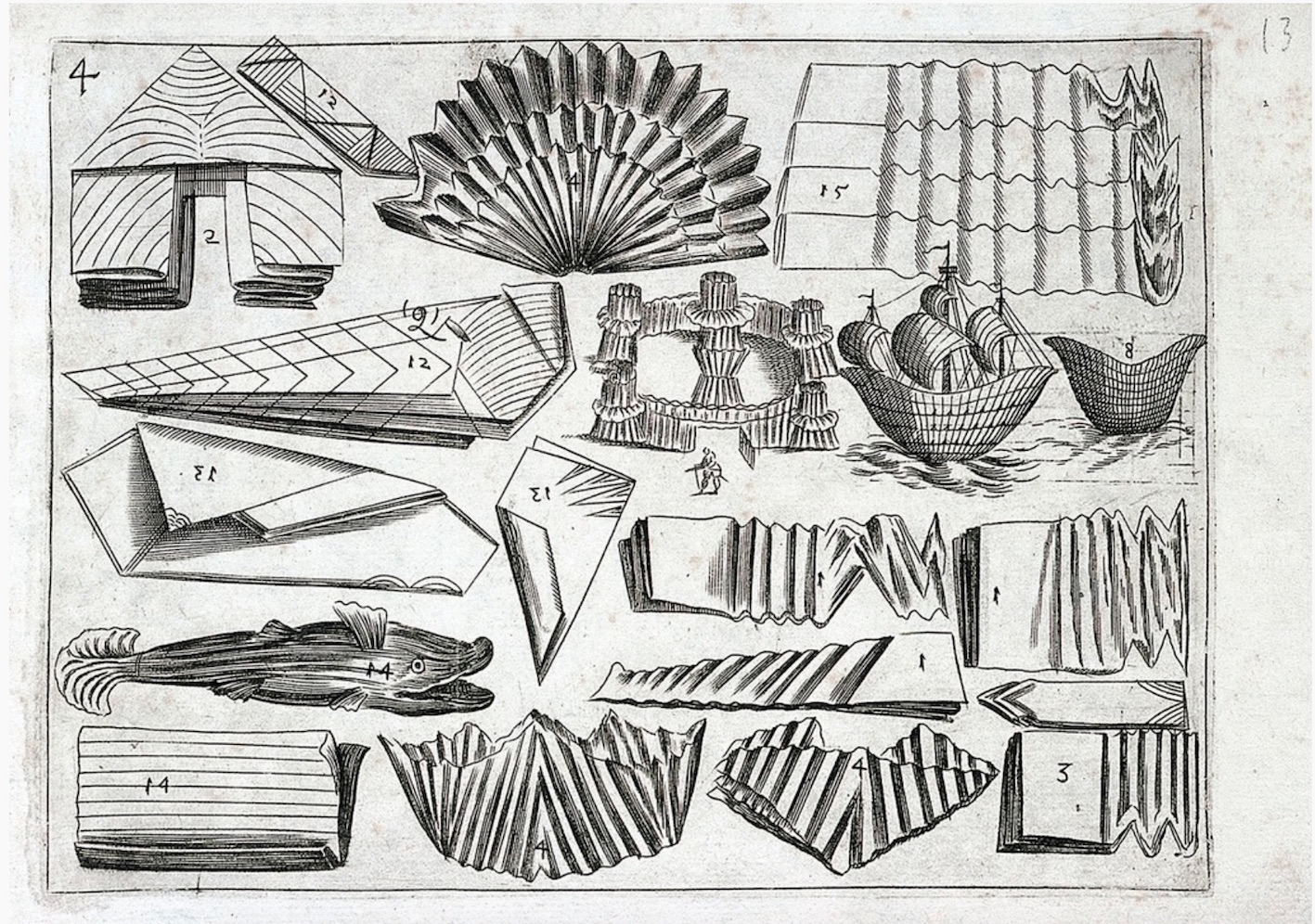

Interestingly enough, Giegher’s treatise cannot be described as a manual in the modern sense. In fact, it does not include folding instructions to reproduce certain shapes, only presenting the readers with ways to exercise their folding technique, so that they would learn which results could be achieved by practising this art, and be inspired to design their own models. Each illustration, therefore, only pictures the napkin in its initial stage, barely hinting to the type and number of folds required to turn it into the correspondent three-dimensional object: as Mattia specifies, the variety of figures that could be created by the expert napkin folder is nearly unlimited, ranging from exotic birds and animals, to marine and mythological creatures, majestic castles and magnificent ships. An entire world could thus flourish on the munificent host’s table, summoned by the hands of skillful stewards able to transform flat pieces of cloth into lavish three-dimensional decorations.

A fascinating insight into a nearly forgotten Renaissance art, Giegher’s Trattato delle piegature stands out as one more token of a cultural world in which three-dimensionality was cherished and chased in almost every aspect of day-to-day life.

Fully digitised copy from Basel University Library available here.