The rise of printmaking and the advancements in scientific research which marked the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries lead to a profusion of books on natural history, as exemplified by Baron George Cuvier’s Essay on the Theory of the Earth (1822; 4th transl. ed., with additions of Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe).

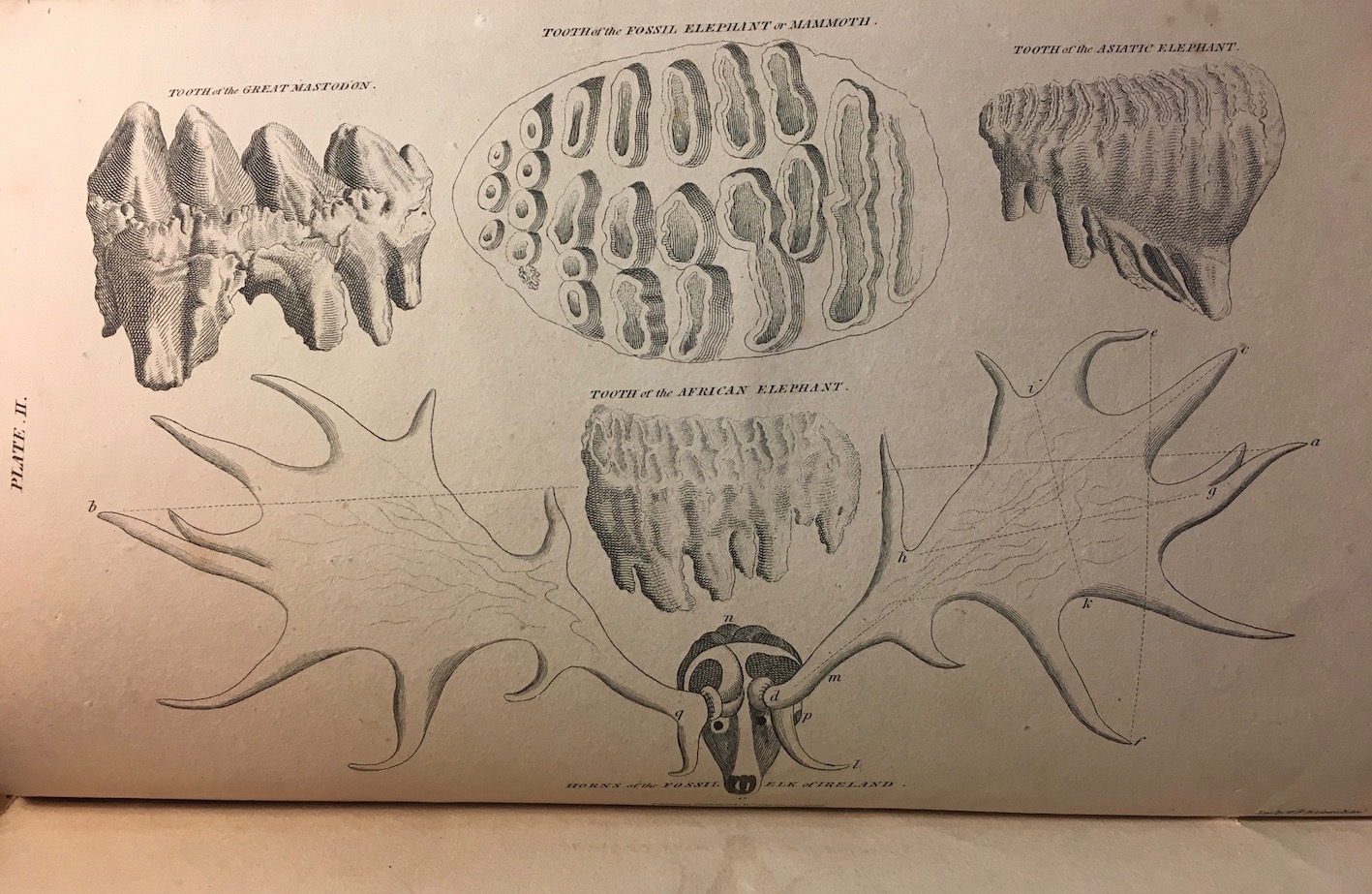

This book focuses on petrification and geological realities, and attempts to convey the three-dimensionality of these elements on a bi-dimensional surface. Cuvier’s theories were illustrated by Robert Jameson, showcasing the relevance of plates in complementing scientific material. These images, located in the appendix of the book, successfully offer the reader a vast array of detailed observations rendered through different techniques.

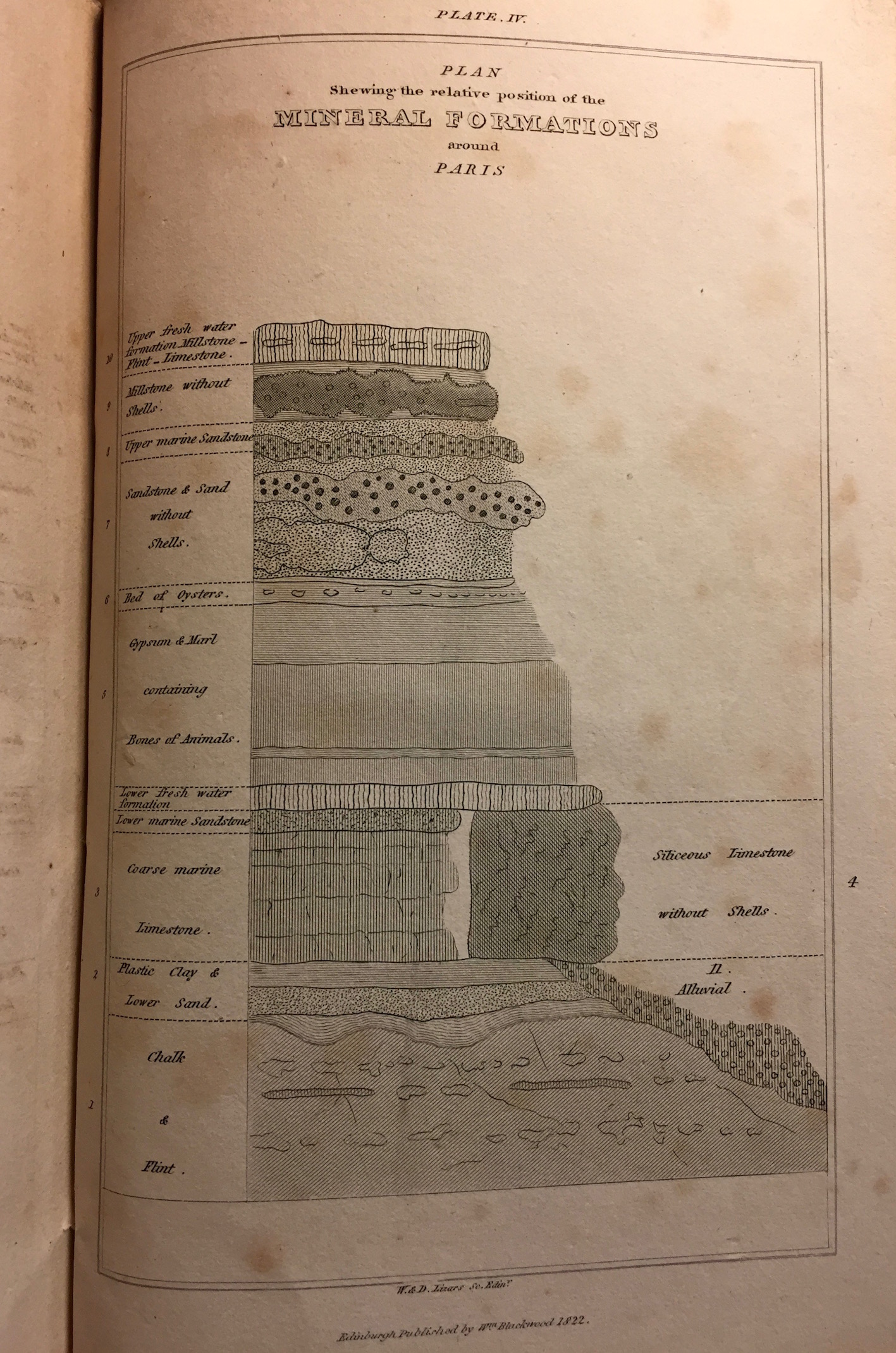

For instance, to explain the properties of the Parisian soil, Professor Jameson schematically depicts the various layers that compose it and analytically subdivides them in a cut-away frontal view. This drawing offers a simplified yet creative perspective of the physicality and depth of the earth which would otherwise not be observable to the naked eye. This exercise of transposing a three-dimensional reality onto a sheet of paper allows for a better access and understanding of natural sciences.

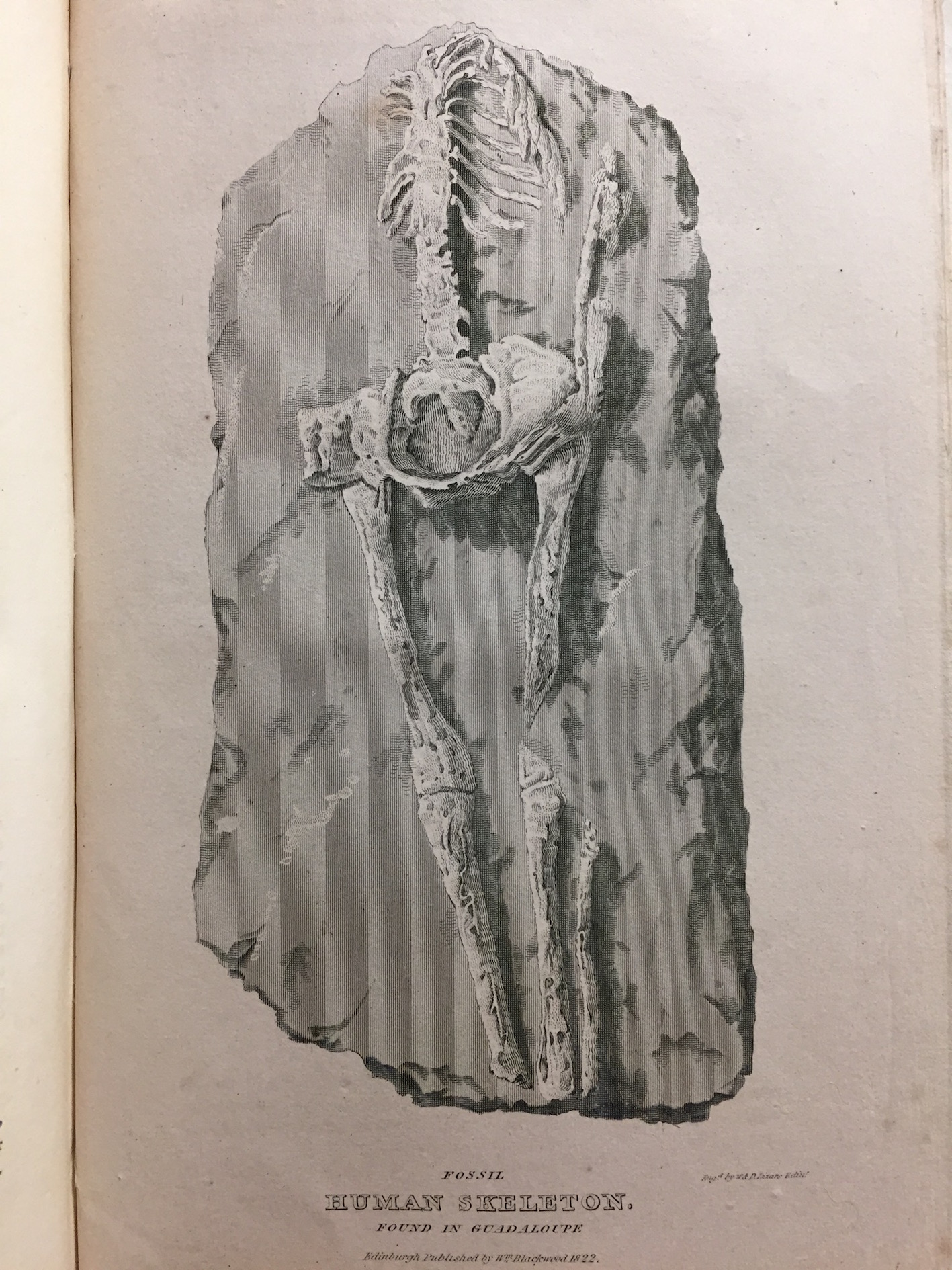

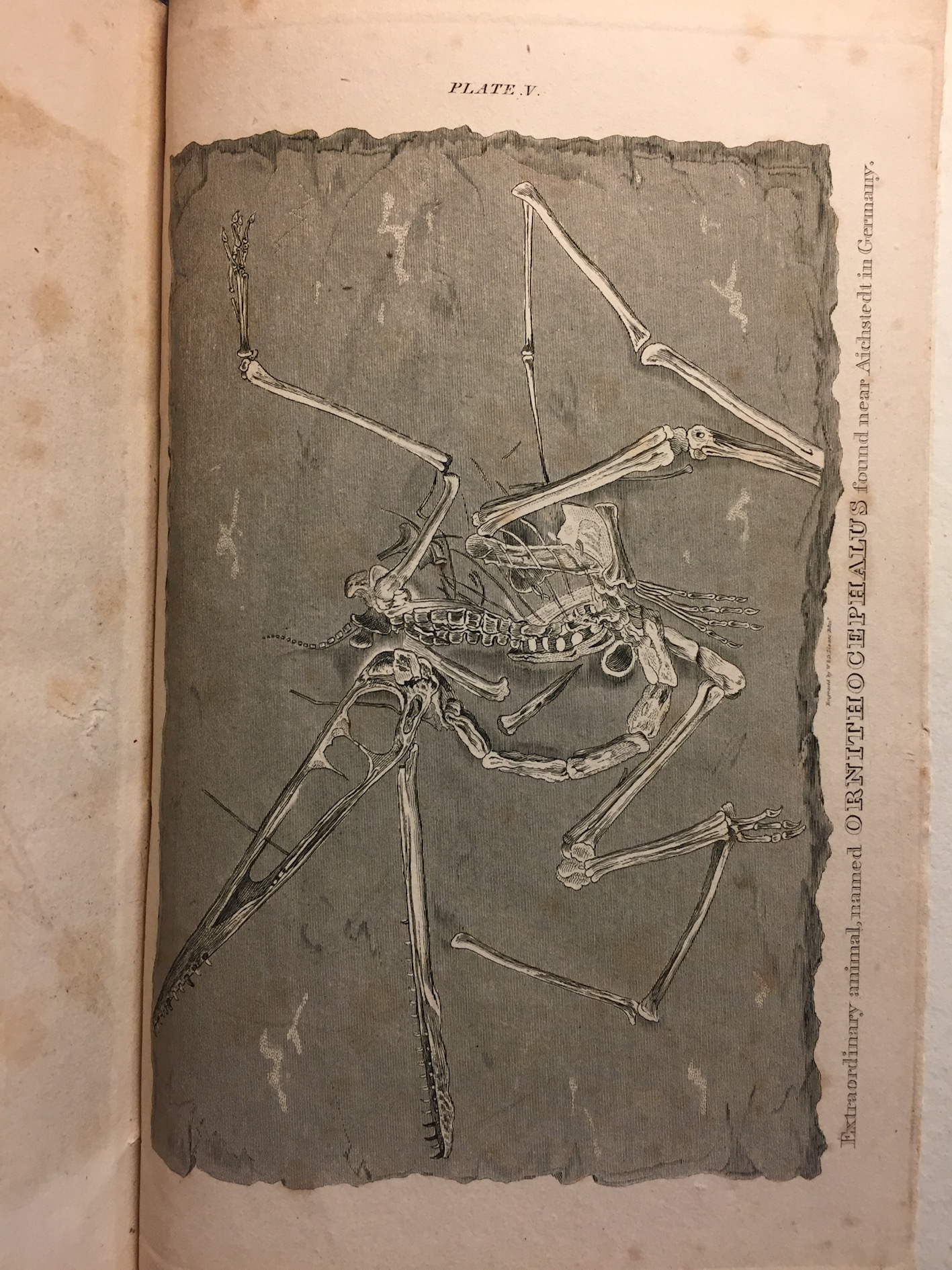

The fossilized remains portrayed in the illustrations of the ‘Ornithocephalus’ and of the human body provide further evidence of how particular artistic techniques enabled the dissemination of scientific material. By setting the white bones up against a dark background, Professor Jameson allows for their features to stand out, emphasizing their physicality. He uses hatching techniques, black and white contrasts, as well as an alternation of dashes to enhance the bone structures’ details.

As a result of the interplay between light and shadow, the materiality of the human skeleton is further enhanced by being incorporated in the actual stone, appearing to rise from it. On the other hand, the tangibility of the animal’s fossil is exacerbated through its distorted and scuffled lay-out, underlining its junctures and articulations. Professor Jameson emphasizes the significance of materiality and the truthful representation of a scientific item by realistically representing the bones, but also by attributing physicality to the stone. Indeed, bestowing creative importance to the background as well as on the main subject-matters strengthens the belief that the studied items are real.

As Enlightenment philosophies spread through Europe, categorization and systemizing became increasingly important tools of scientific knowledge-production, which can be observed through these plates. Informative titles and captions accompany the illustrations, as if to underscore their scientific credibility. The artist employs subtle technical details to convey precise information, seen in the application of geometric lines which define the fossil’s dimensions, shape and size. The inclusion of lists to categorize the layers of the soil also offers further indication regarding the earth’s properties and depth.

Notwithstanding the scientific nature of these plates, they are also inscribed within an aesthetic dimension; everything about them suggests they are more than just informational tools. The use of specialized engraving techniques, the particular framing of the objects and the elegant cursive fonts showcase that these illustrations are a fusion of art and science. Indeed, the tight intertwining of these two domains explains the importance of accurately representing Cuvier’s theories through illustration which transcend their informational function, elevating themselves to the realm of the arts.

Maïa Sonoko Heegaard and Maria-Clotilde Czartoryski Scimone

Fully digitised copy of the 1827 edition from the University of California Libraries is available here.