To begin this series of Thinking 3D Book of the Week, we thought it would be best to start from the beginning, or, more precisely, from where this project conceptually began: Leonardo da Vinci.

After a visit to the British Library, on a train ride back from London, Laura and I began discussing the concept of what how the ability to communicate three-dimensional concepts developed both in terms of concept and ability to depict three-dimensional objects; the study of this development across disciplines, technology, and popularity would eventually become Thinking 3D. Our starting point in this narrative has always been

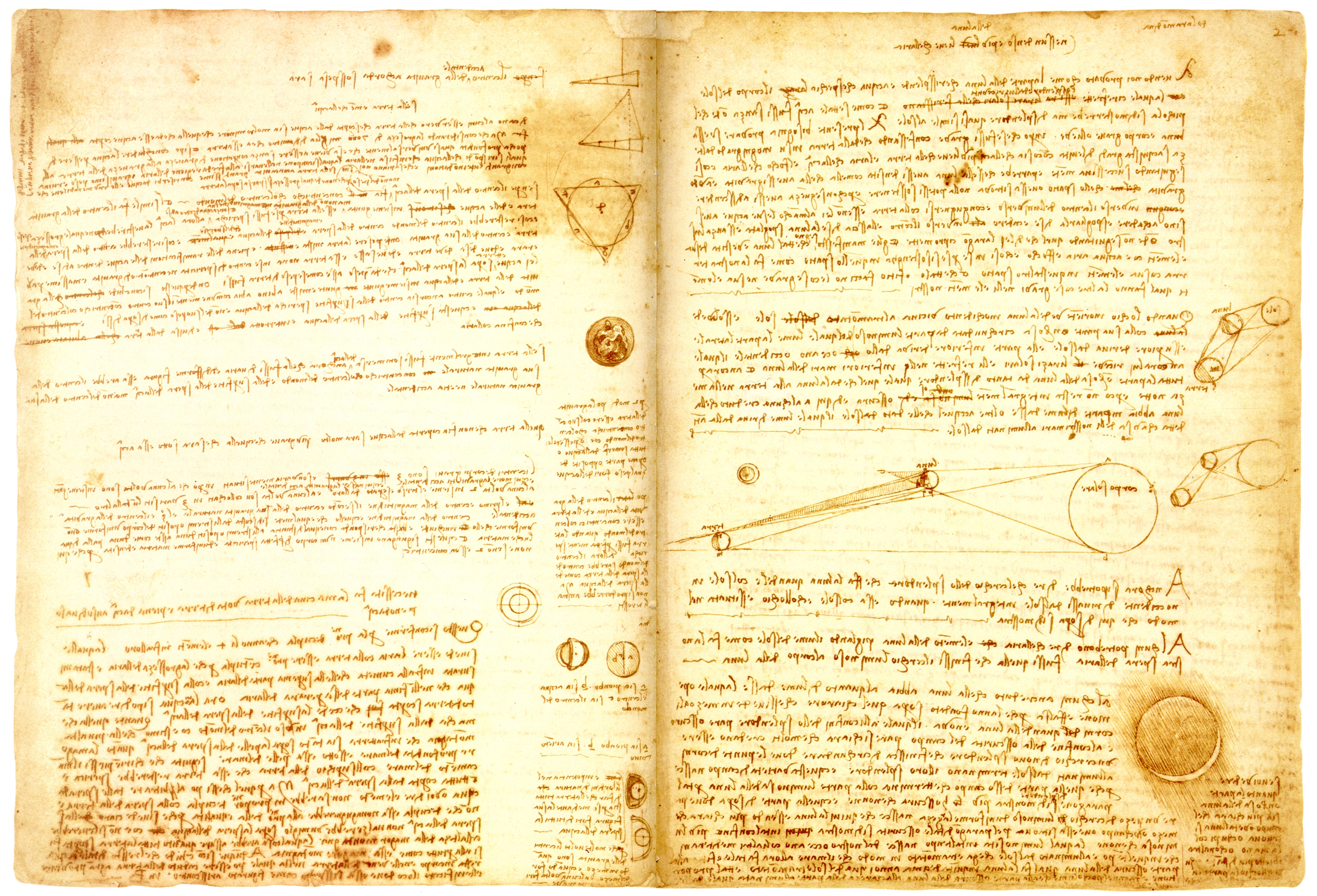

Leonardo; he certainly did not invent perspective drawing or three-dimensional conceptual structures, but he was one of the finest practitioners of working out hard-to-communicate concepts in three-dimensional sketches. His surviving notebooks are testament to his ability, and perhaps his most in-depth and expertly executed notebook is the Codex Leicester.

The Codex Leicester is a relatively small manuscript, 18 leaves of folded paper, with 72 pages of text and illustrations total. It was likely composed in the latter half of the first decade of the 16th century during a time in which Leonardo was living and working both in Florence and Milan. It was owned by Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester (where the codex acquired its name) and remained in the Leicester library at Holkham Hall for over 200 years, when it was then acquired by Armand Hammer, and finally by Bill Gates in 1994.

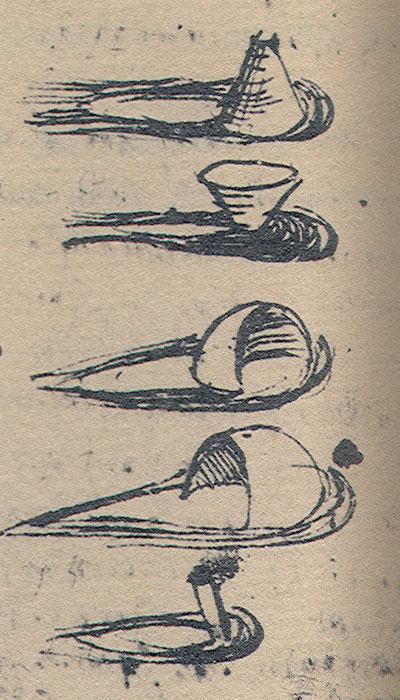

Leonardo deals with many subjects in this short notebook, but mainly focusses on heavenly bodies, geology, and the motion and control of water. The book is full of Leonardo’s historical narrative and on his own observations and experiments; it is an unusually coherent notebook which is largely text, but many of the concepts that he grapples with are worked out in thumbnail sketches in the margins and near the appropriate texts. For example, in his discussion about the displacement of currents in water, he experiments with several geometrical shapes which cause currents to react in different ways.

The Codex Leicester, along with the Codex Arundel, Codex Atlanticus, and the Codex Forster, is a wonderful glimpse into the mind of a Renaissance genius grappling with ability to communicate to his fullest abilities the three-dimensional world around him.

For a full facsimile of the Codex Leicester, see Leonardo da Vinci: the Codex Hammer, formerly the Codex Leicester (Royal Academy of Arts, 1981).