The nightjar, or ‘goat-sucker’ of Carolina: a bird so called from the myth that it swoops down from the rafters and suckles on the teats of goats at night. Here it is depicted in mid-pursuit of the mole cricket, which travelled from its native Europe to the east coast of North America during the founding of the ‘New World’ and thrived there – much like the author and illustrator of the two-volume The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, Mark Catesby.

Catesby first journeyed to Virginia by way of his brother-in-law, who introduced him to various wealthy landowners so he could observe the local wildlife. On his return, he was funded by a host of sponsors to create a more comprehensive compilation of the flora and fauna in south-eastern North America. Previously undocumented, Catesby’s work on these lands provided an exemplary demonstration of British naturalism in the Age of Discovery.

Each volume contains a page entitled “A catalogue…with the Linnaean names.” Carl Linnaeus was a Swedish naturalist who coined the process of “nomenclature”, whereby each organism is given its own specific name and category.

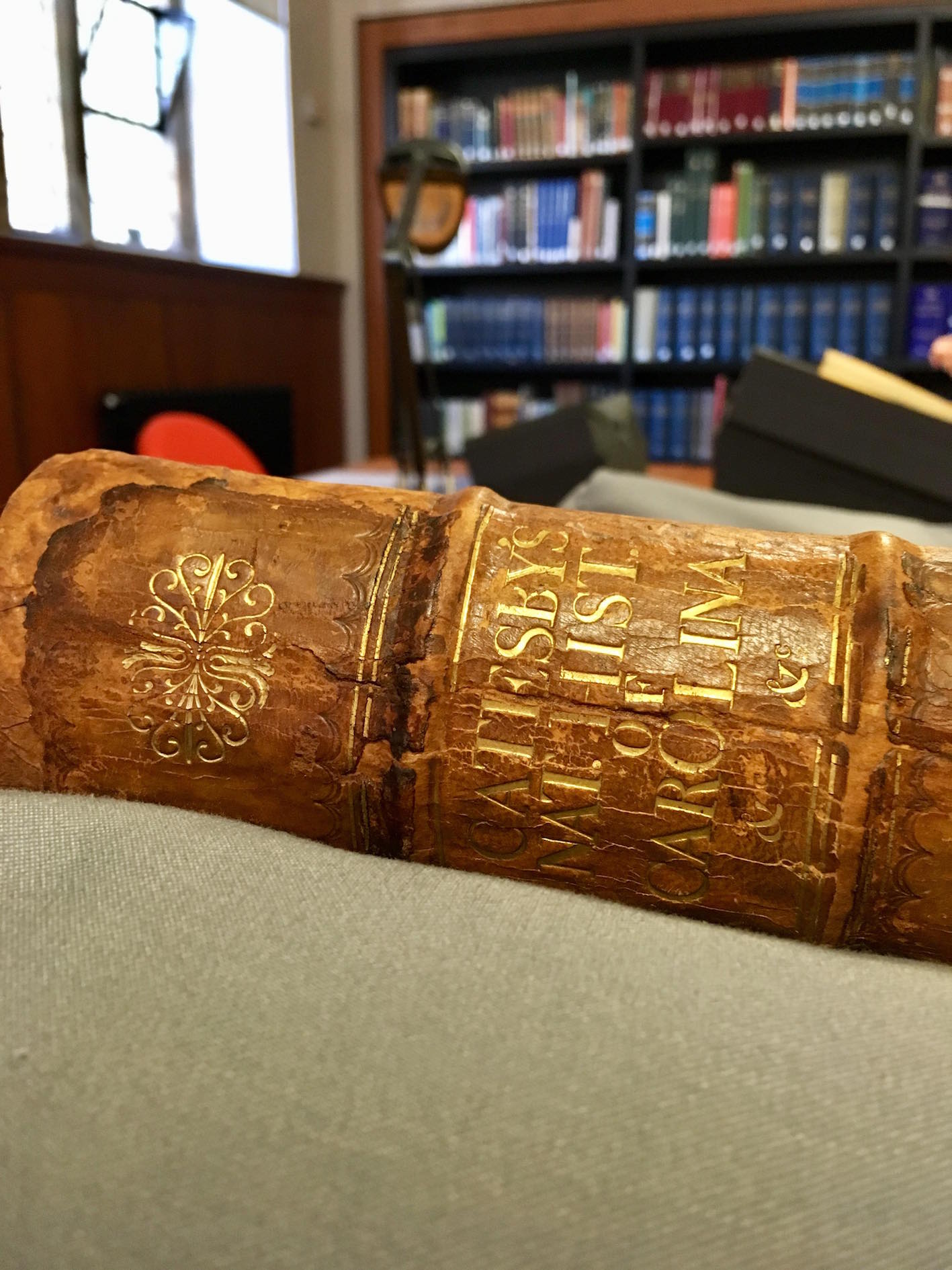

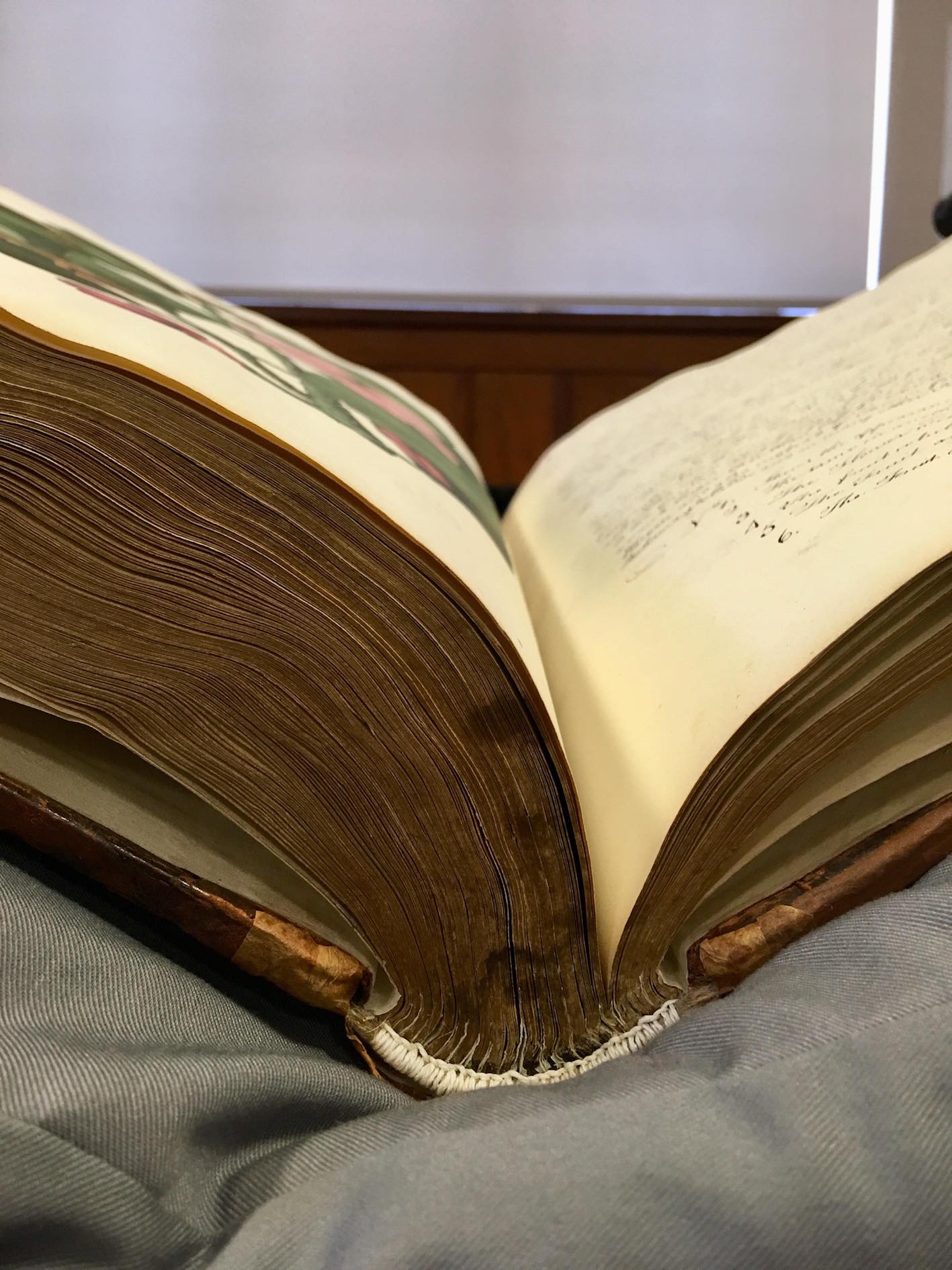

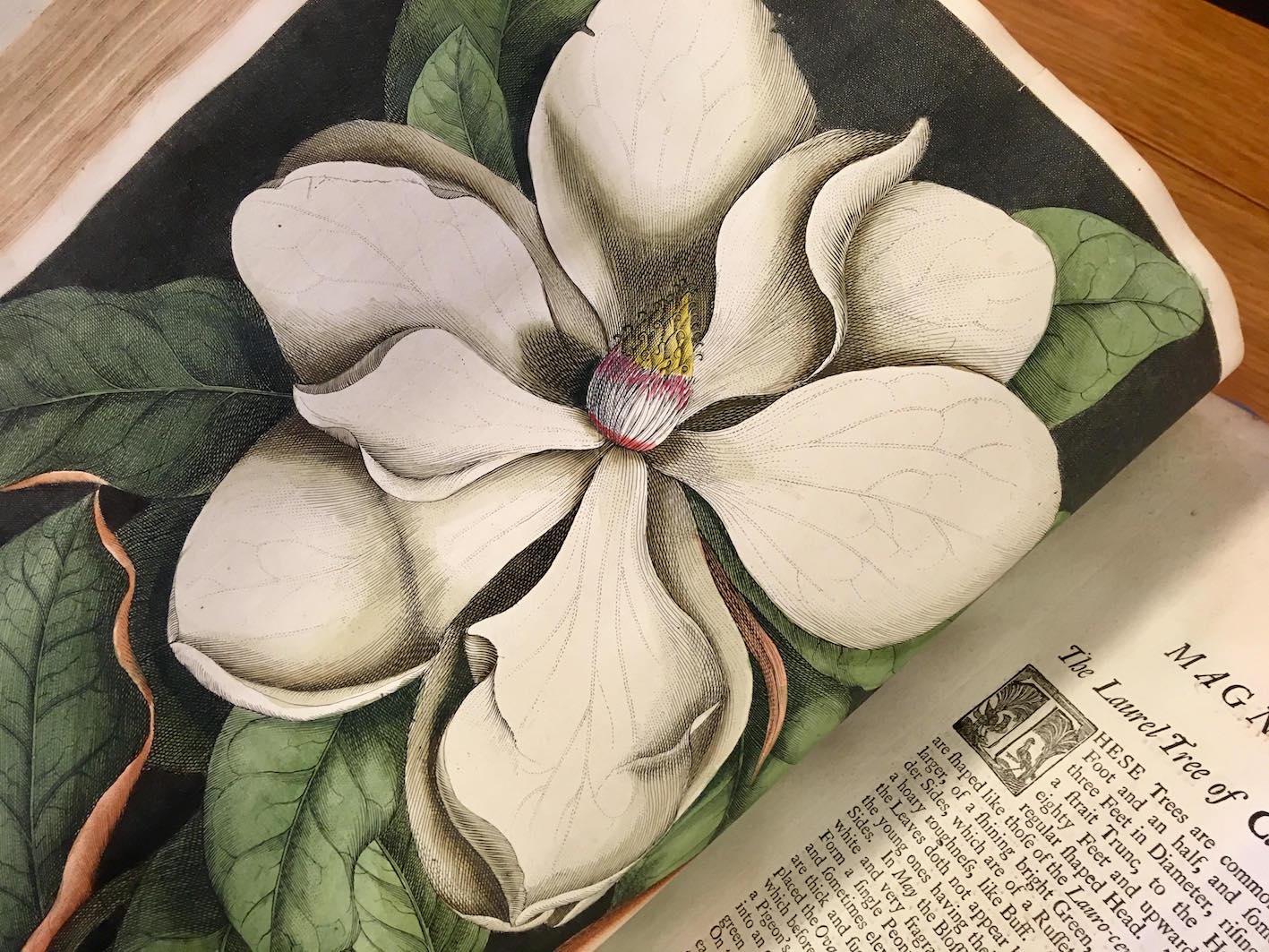

The sheer scale of the books is impressive in itself. Their heavy weight, thick leather binding, and sizable pages encourage us to physically participate in the book’s ritual. As we progress, each page becomes more artistically driven and compositions become more thoughtful, combining art and diagrams.

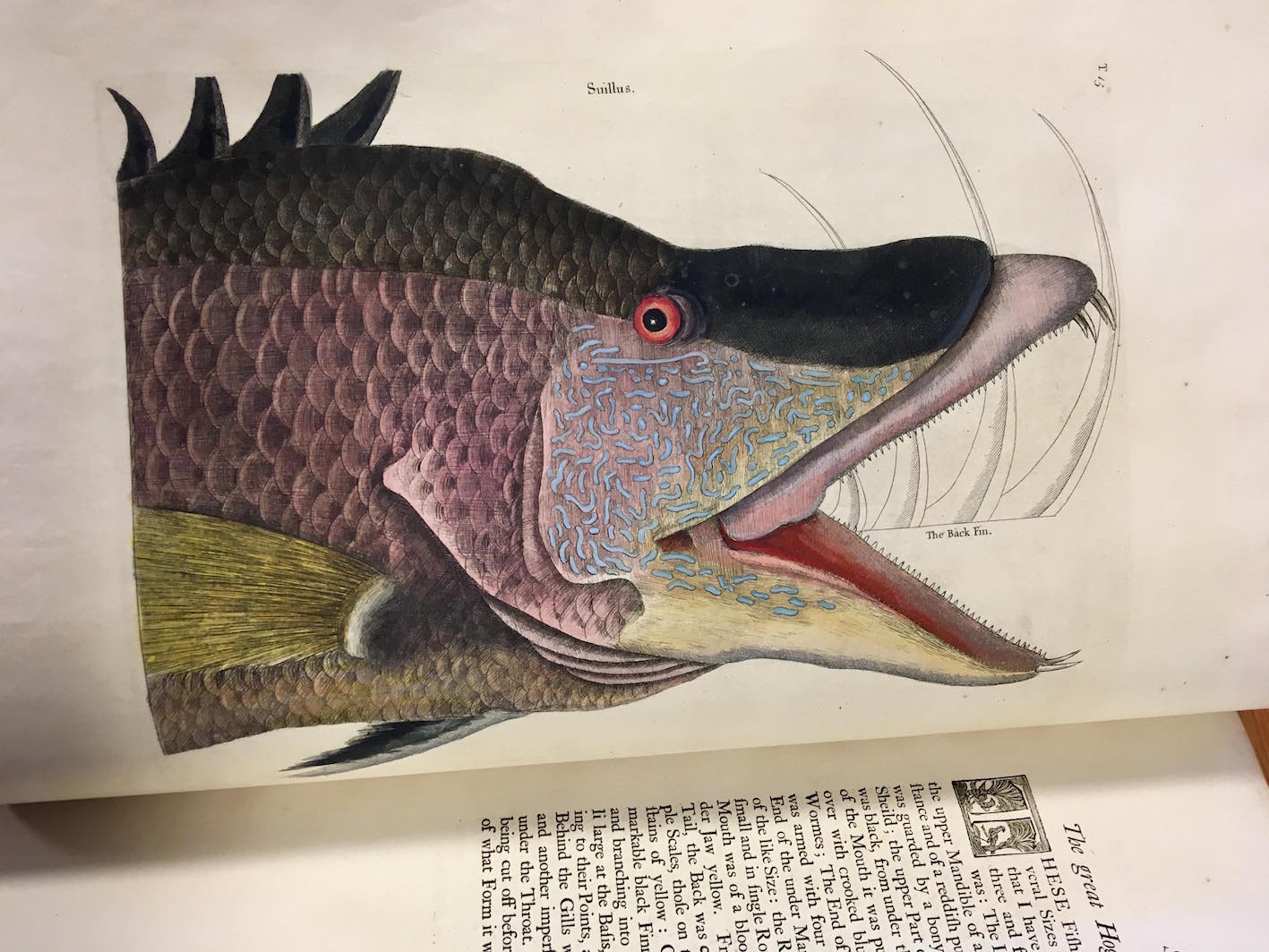

Whereas volume one is dedicated purely to birds, volume two offers a more extensive range of species: fish, crustaceans, reptiles, insects, plants, and various mammals. The vibrancy of colour is a prominent characteristic: he used highly pigmented watercolours to animate his subjects. His ‘painted finch’ and ‘hogfish’ particularly demonstrate the liveliness of his greens, yellows and blues, unparalleled in contemporary wildlife observation.

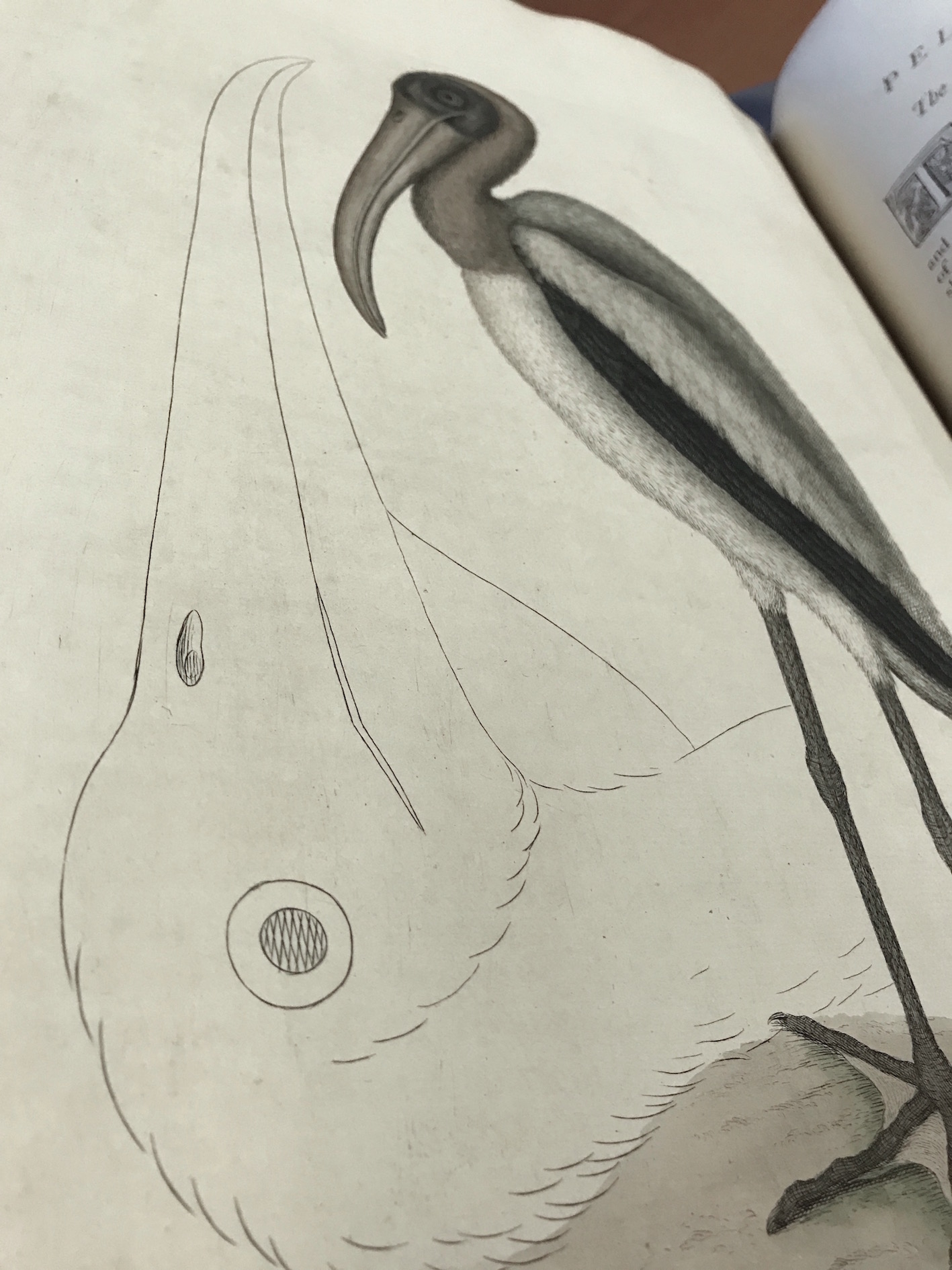

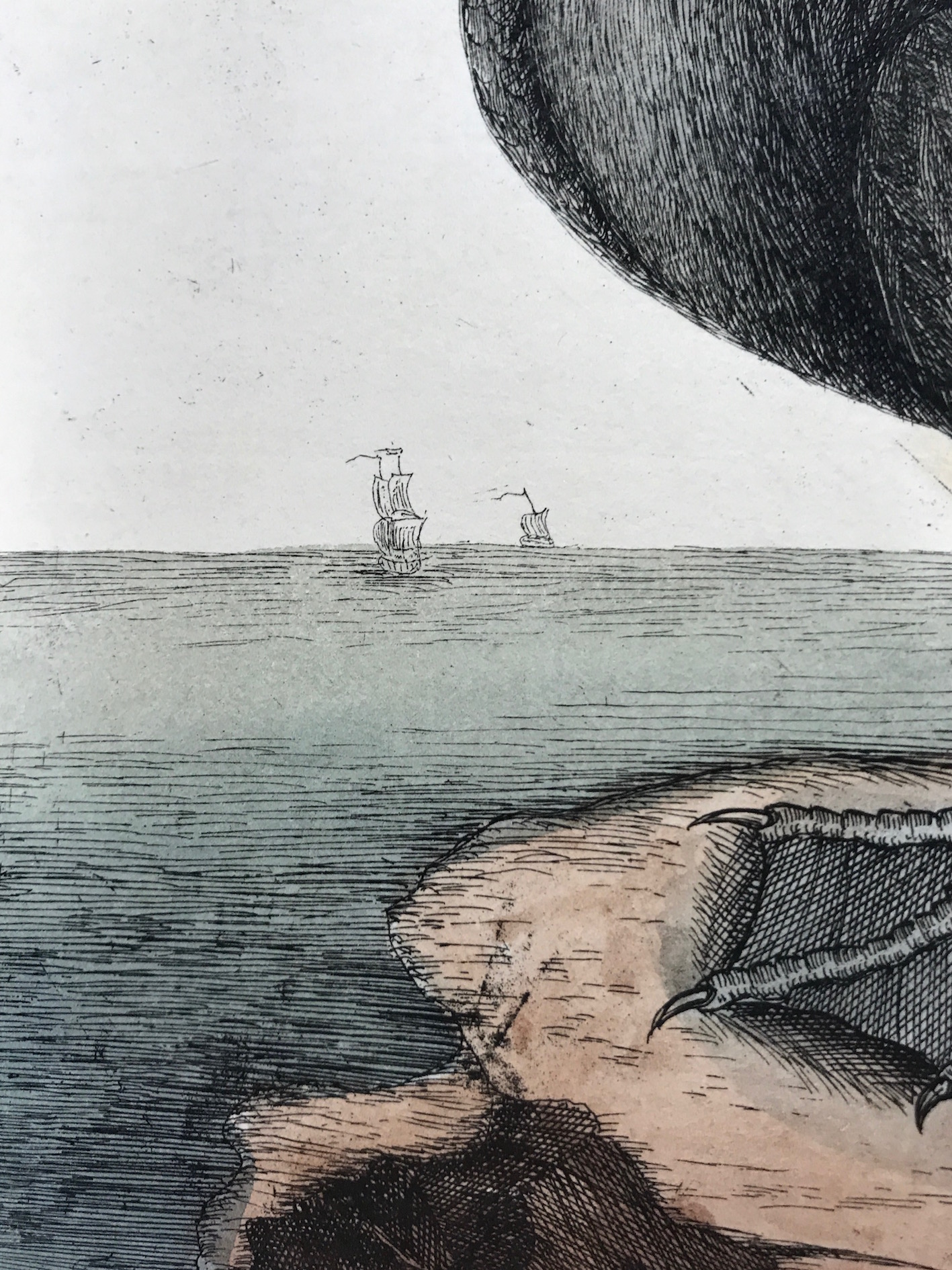

Fine pen handling and cross-hatching is consistent and whilst turning the pages, we notice the amateur artist’s hand, for Catesby only received minimal training in etching from French artist Joseph Goupy, who taught him to create easily understood images.

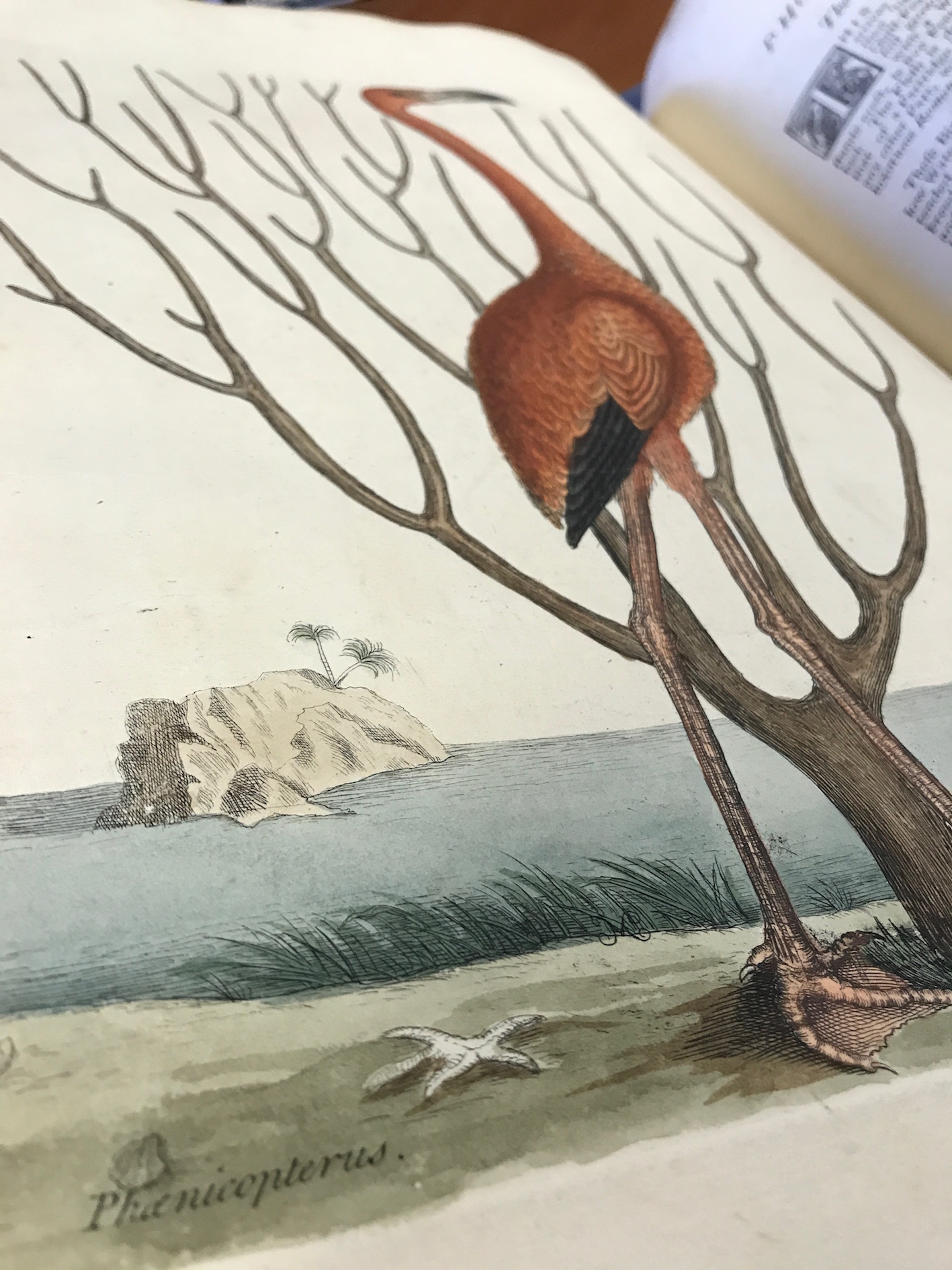

Catesby’s eccentricities are most interestingly encapsulated in his background scenes. In one, an island floats in the waves behind the flamingo, with a starfish splayed on the sand; in another the ghostly sketch of a ship sails on the horizon behind the ‘Nobby.’ Catesby evidently enjoyed his work as an art form, as well as a scientific method of documenting nature. While it is clear from these intricate additions that Catesby drew birds from life, observing them in their natural surroundings, the absence of an environment in his marine drawings equally shows that he painted his fish from dead specimens.

The aesthetic advantages of Catesby’s “Flat, tho’ exact manner,” while ignored by contemporaries, shine through today as his greatest achievement in Natural History. As David Wilson notes (Wilson 1971, 172), this naturalist-come-artist proves his creative capabilities by fusing the dualism put forth by eminent art historian Erwin Panofsky – for Catesby’s book serves both as a “document” – a repository of naturally accurate drawings – and a “monument” – a work of art in itself.

Daisy Treloar and Rachel Anderson

Reference: Wilson, David. “The Iconography of Mark Catesby.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 4, no. 2 (Winter 1970-1971): 169-183. Available online via JSTOR.

Fully digitised copy from the Smithsonian Libraries is available here (vol. 1) and here (vol. 2).