In 1711 a new treatise on architecture and geometry was published in Parma. Its author, Ferdinando Galli Bibbiena (or Galli da Bibbiena, or Bibiena), was one the most famous scenographers of his time in Europe; just three years earlier, in 1708, he had been appointed as supervisor to the wedding festivities of King Charles III, whom this new treatise was dedicated to.

The son of a painter, Bibbiena studied painting, perspective and architecture, yet he soon earned a reputation for his scenic designs and began working for the theatre, a confluence of the three disciplines he was most learned in.

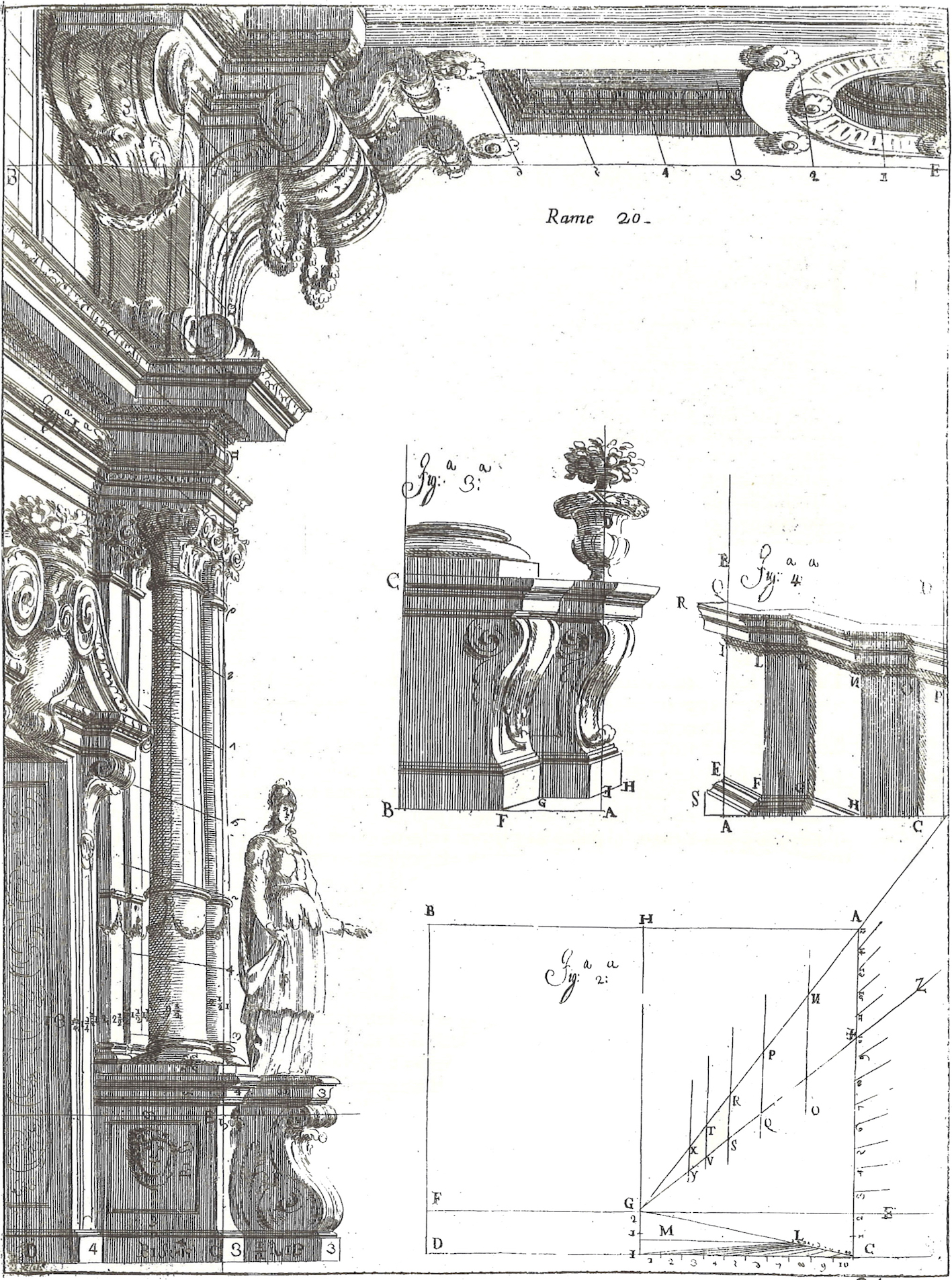

Bibbiena’s Architettura civile is divided into five sections: the first on geometry, the second on architecture, the third on perspective, the fourth on scenography, and the fifth on mechanics. Despite its title, the book is clearly more focused on illusionistic painting and scenic design rather than on architecture. Although very similar to Andrea Pozzo’s Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum in regards to the illusionistic representation of architecture on walls and ceilings, Bibbiena’s treatise is extraordinarily innovative in the use of perspective applied to scenography.

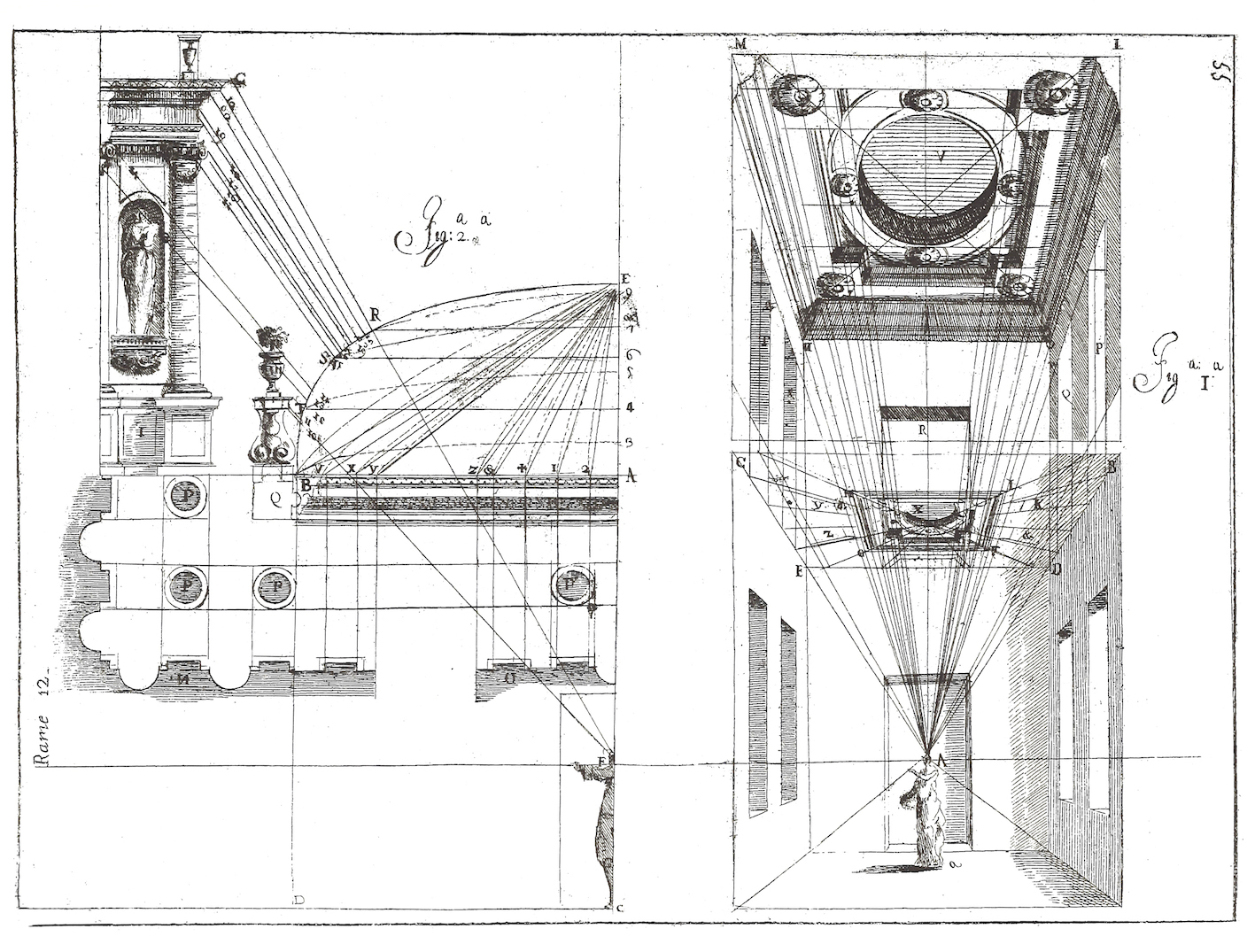

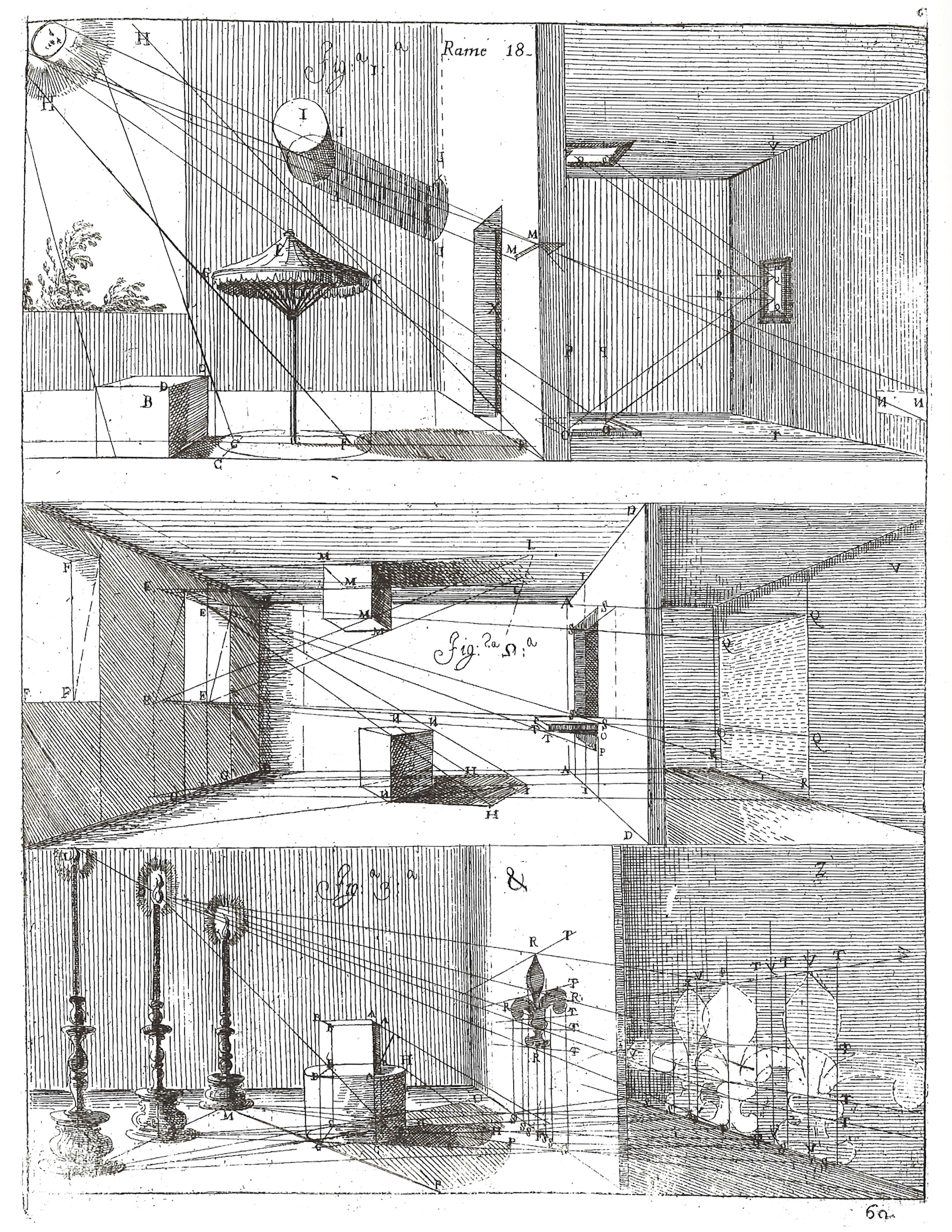

Bibbiena emphasises the difference between a quadratura painted on a wall and a theatre set, as well as the mistakes that might occur when the same rules are used indiscriminately. Theatrical space is built with specific features, and the author explains each of them: lighting is totally artificial, the stage is slightly inclined, and the view changes from seat to seat.

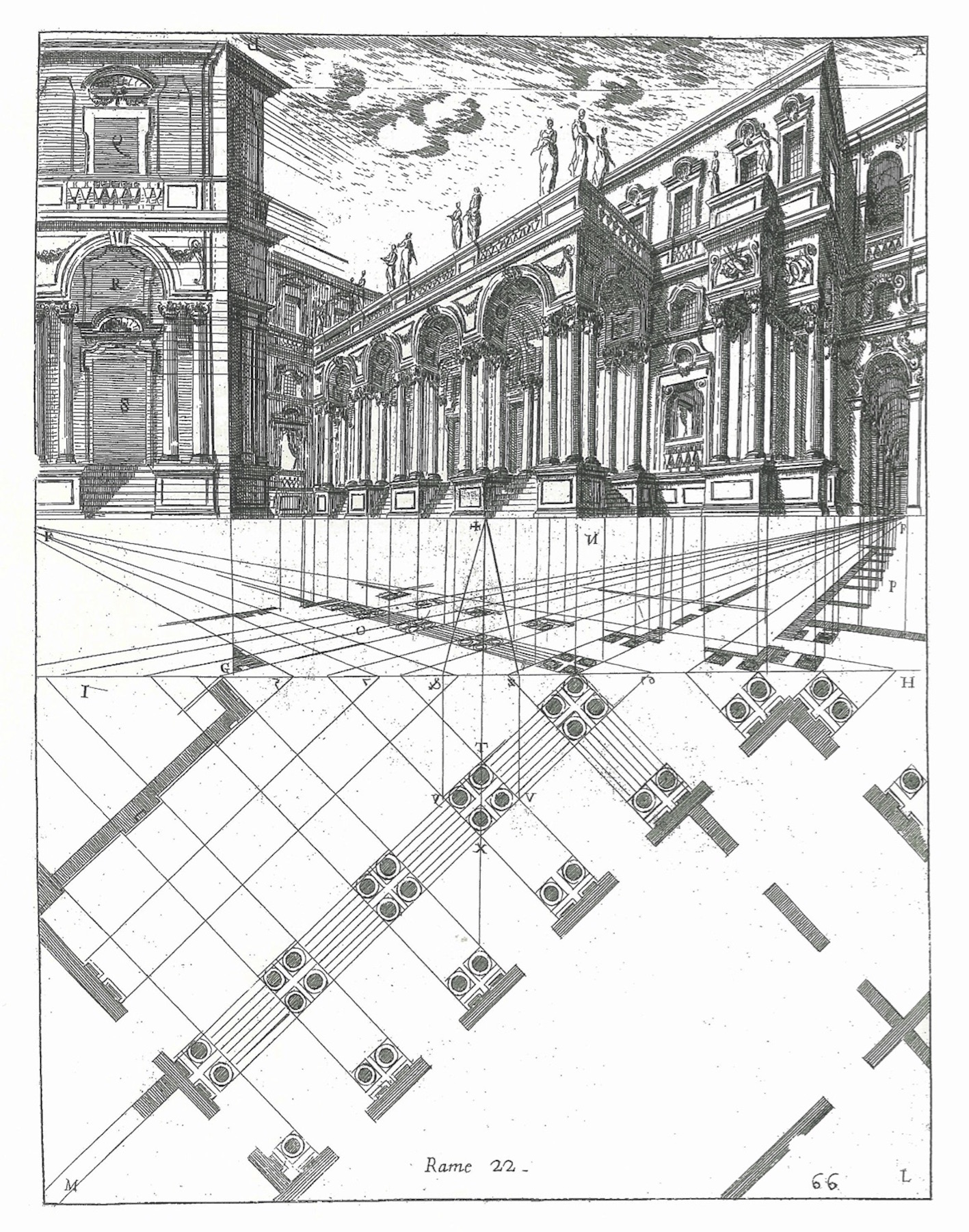

Traditionally, designs for theatre sets were based on one-point perspective, with the vanishing point in the centre of the composition. In such kind of perspective, all elements that are parallel to the picture plane are drawn as parallel lines, while all elements that are perpendicular to the picture plane converge at a single point on the horizon. As a consequence, all lines running from points above the horizon are inclined downwards and all lines running from points behind the horizon are inclined upwards. This effect can be easily represented in a painting, but it becomes more problematic when applied to a series of wooden panels carved along the outlines: in fact, in order to converge at the central point, the lower profiles necessarily need to “raise” from the ground, creating an unconvincing – if not disturbing – effect.

These innovations introduced by Bibbiena are surprising. He fixes the horizon line at 2 braccia from the ground, and puts only the lines above it in perspective; on the contrary, all lines behind the horizon are kept parallel to the ground, in order to avoid empty spaces between the panels and the floor. This is made possible by the fact that, on a large stage, the low gradient of the projections below the horizon can be convincingly approximated to parallel lines, without altering the perception of perspective.

Bibbiena soon realized that one-point perspective worked only with the observer standing exactly in front of the scene and with his eyes at the same level of the horizon line. Traditional Baroque sets were unsuitable to the classical organization of theatres (on rows of boxes facing the stage from different angulations) as the three-dimensional effect used to get completely lost from the sides and from the higher rows. For the first time ever, Bibbiena introduced in a treatise on scenography another kind of perspective, organized on two points. Avoiding the centrality of the viewpoint and depicting buildings from different angulations enabled also the audience on the sides to perceive the three-dimensional effect. The only problem was that in two-point perspective no elements were parallel to the picture plane, this made the carving of the scenes impossible and unsuitable to the inclined stage. Once again, the solution is brilliant: everything is kept above the horizon line, as if the observer’s eyes were at the same level of the ground. The horizon corresponds to the level of the floor, so the entire scene can be painted as a unique background.

Bibbiena’s inventions had an extraordinary impact on late-Baroque theatre, and with its four generations of scenographers the Galli Bibbiena Family dominated the entire 18th Century.

Do you want to learn more on how to interpret Bibbiena’s plates? Have a look at this video!

The copy of L’architettura civile now preserved at Sapienza - Università di Roma (Biblioteca Centrale della Facoltà di Ingegneria G. Boaga) is fully digitised on Google books.