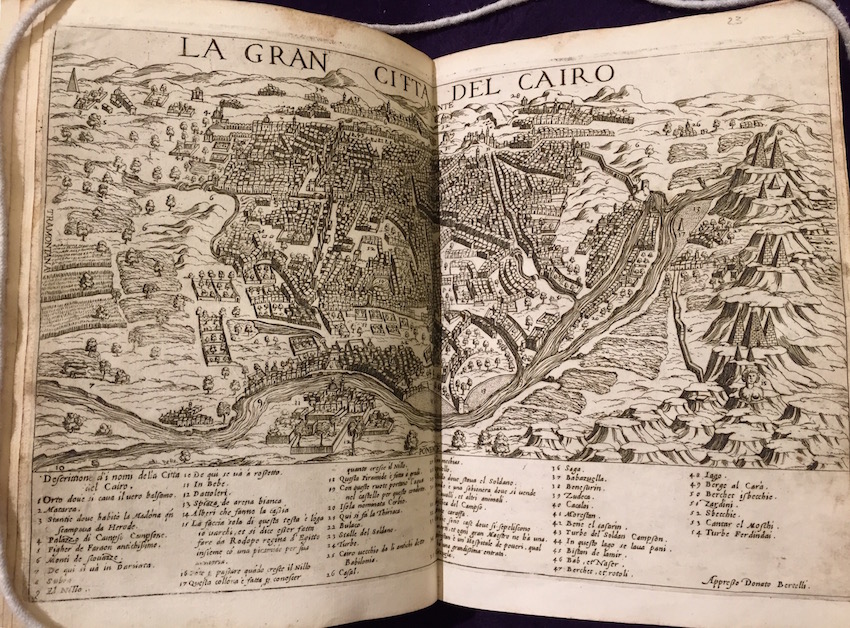

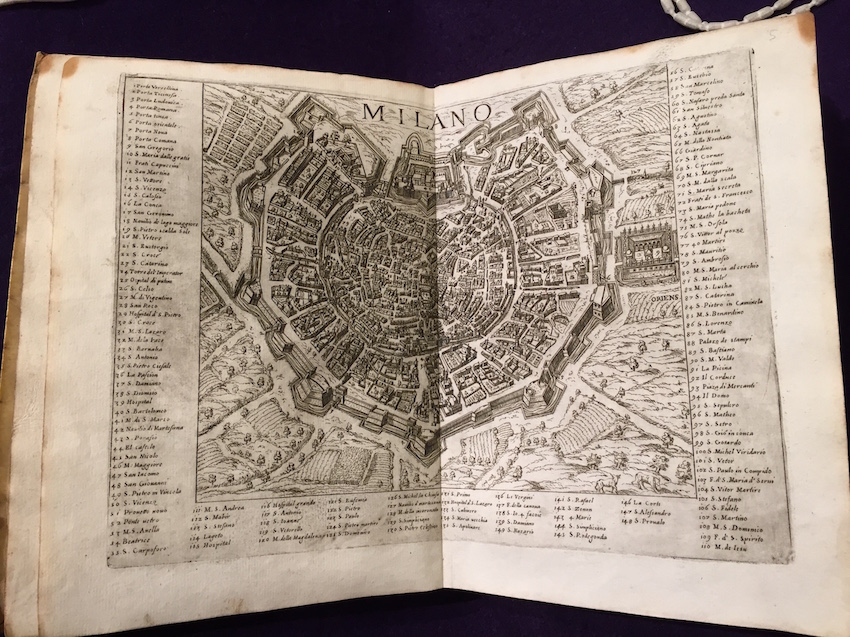

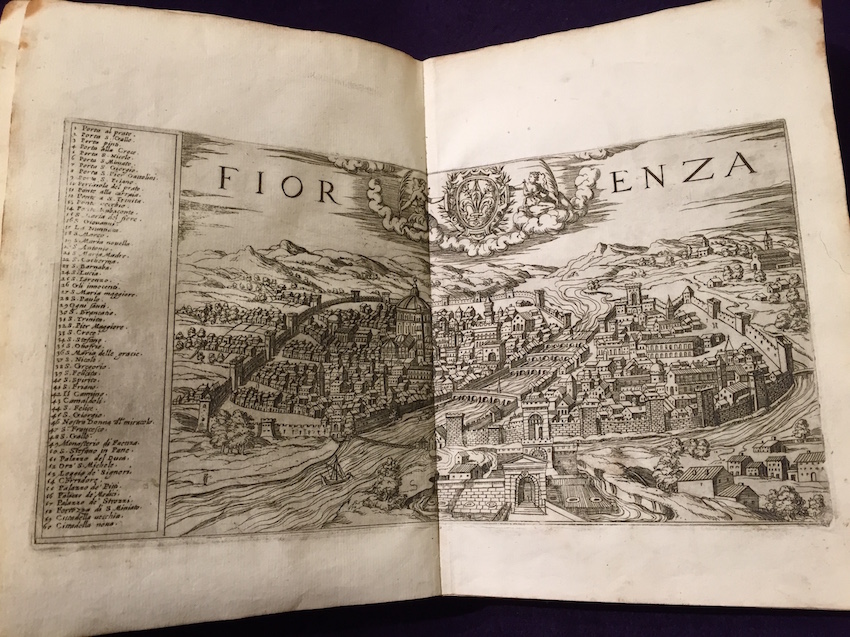

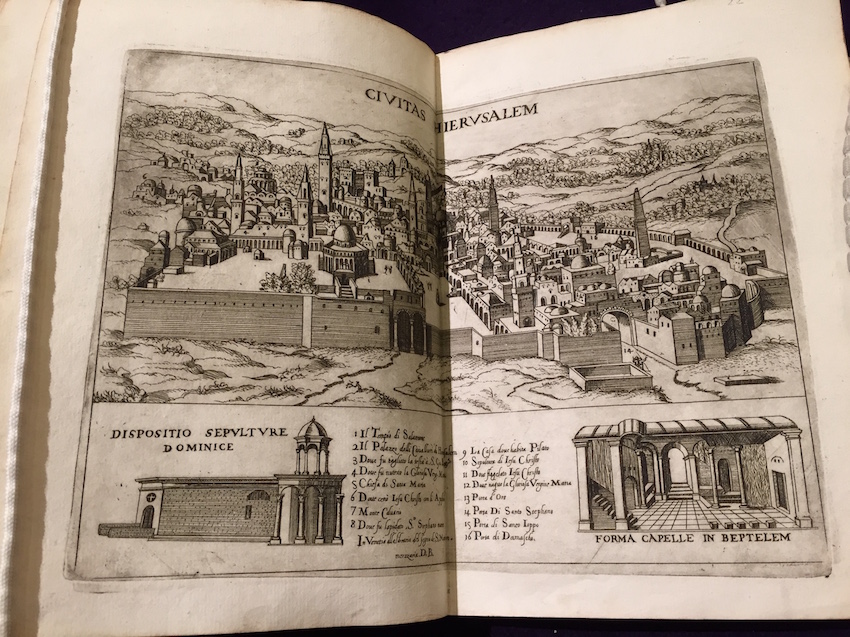

Le vere imagini et descritioni delle più nobilli [sic] citta del mondo by the Venetian Donato Bertelli (active in the second half of the sixteenth century) is a collection of maps, portraits of people, and other relevant images of the most important cities of the sixteenth century. Such cities and people are for the majority European (and largely Italian), without excluding cities from North Africa and the Middle East such as Tripoli, Costantinopole, Cairo, and Jerusalem.

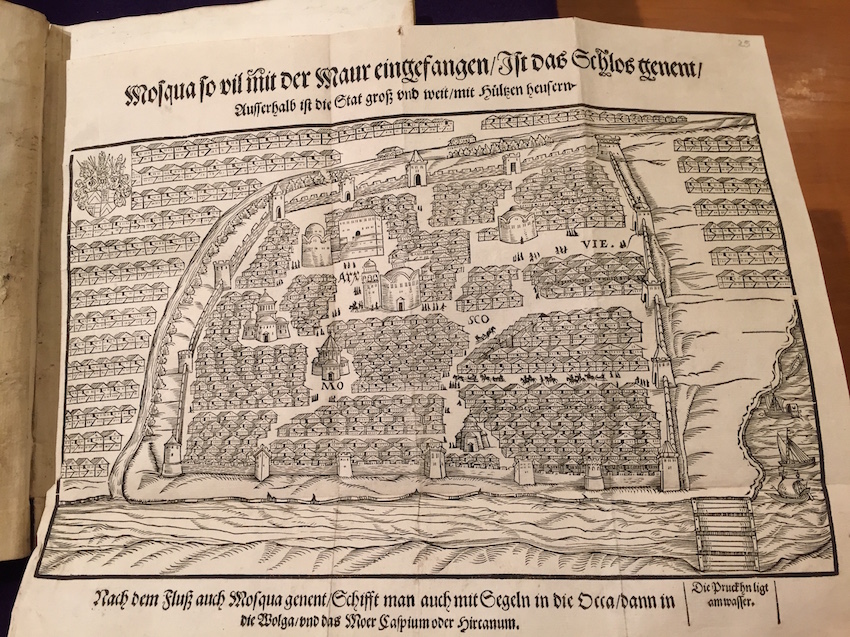

The first section of the text (c. 1-25) is devoted to maps, predominantly drawn through the bird’s eye technique, as in the cases of the maps of Venice and Milan.

Some maps, however, adopt a more frontal view (for instance Florence, Rome, and Lion), that increases the 3D effect of the representation.

This latter technique becomes more prominent when notable places are represented, as in the case of Jerusalem.

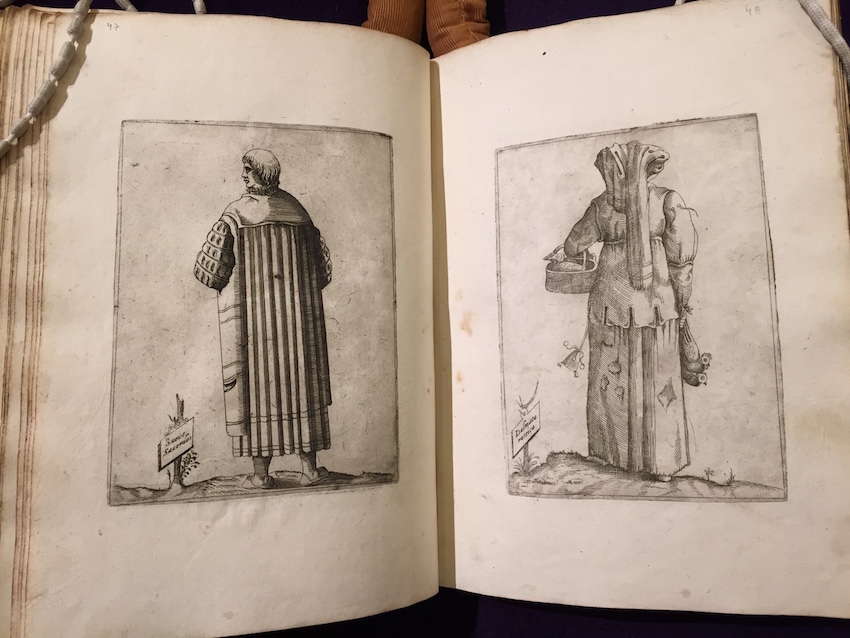

The last section of the book is comprised of representations of people from the different areas featured in the book. These characters, both male and female, are depicted wearing their different regional costumes and holding tools from their various professions.

While each city map is spread over two pages, portraits of people are printed on a single page, with two portraits facing each other. Throughout the entire text, pages featuring images are followed by two blank pages.

The most interesting aspect of Bertelli’s book is its use of three-dimensional elements. The first example that the reader encounters is a German-language map of the city of Moscow, which is larger than the rest of the book and folded onto itself, to be extended at will.

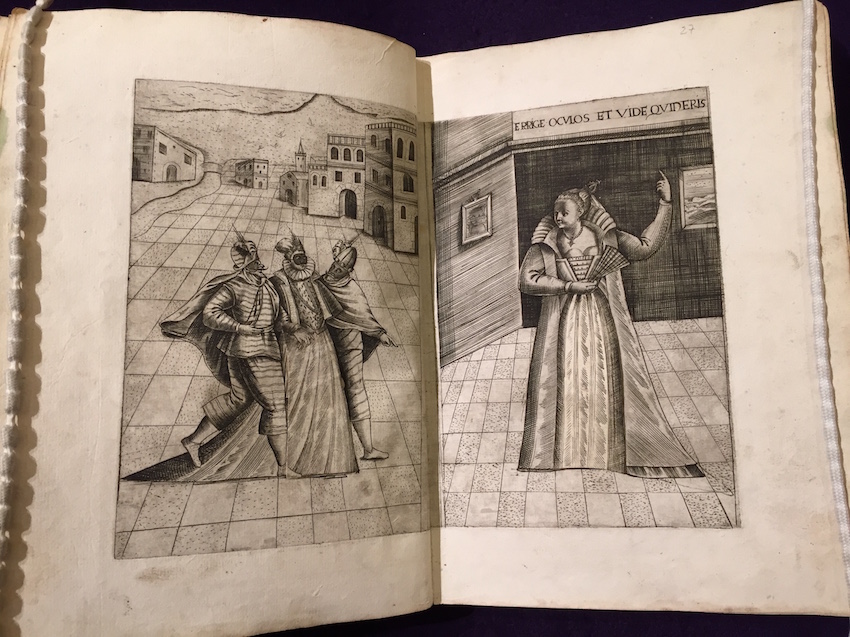

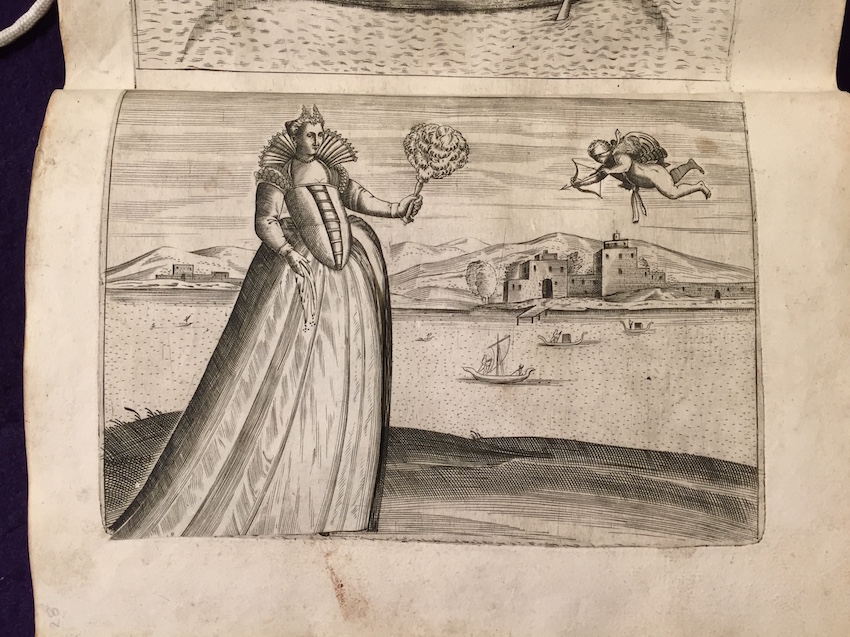

The three-dimensional technique reaches its full potential in the central section of the book, devoted to the depiction of one of the most controversial aspects of the time: Venice and its notorious courtesans—the beautiful, famous, talented and often powerful women who were the pride and the shame of the city at that time—here represented through scenes in their daily life. The pages dedicated to the courtesans (c. 26-32) are seemingly “normal” pages that only upon careful exploration reveal small flaps, that disclose to the onlooker the secrets of the courtesans.

The flaps are minute, sometimes minuscule, and overall appear almost hidden in the book: hard to spot visually, perceptible mostly to the touch alone, and therefore rather easy to miss. In fact, the best way to make sure to spot all of the book’s 3D features (and to uncover all the secret of the courtesans) is to pass a careful finger on every page that looks “suspicious”—i.e., on every and each page that happens to depict a courtesan.

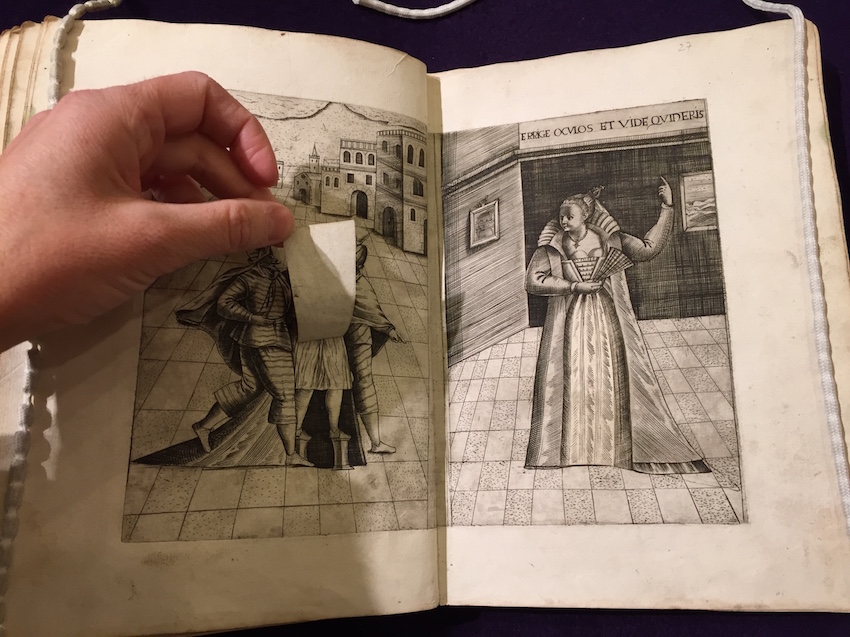

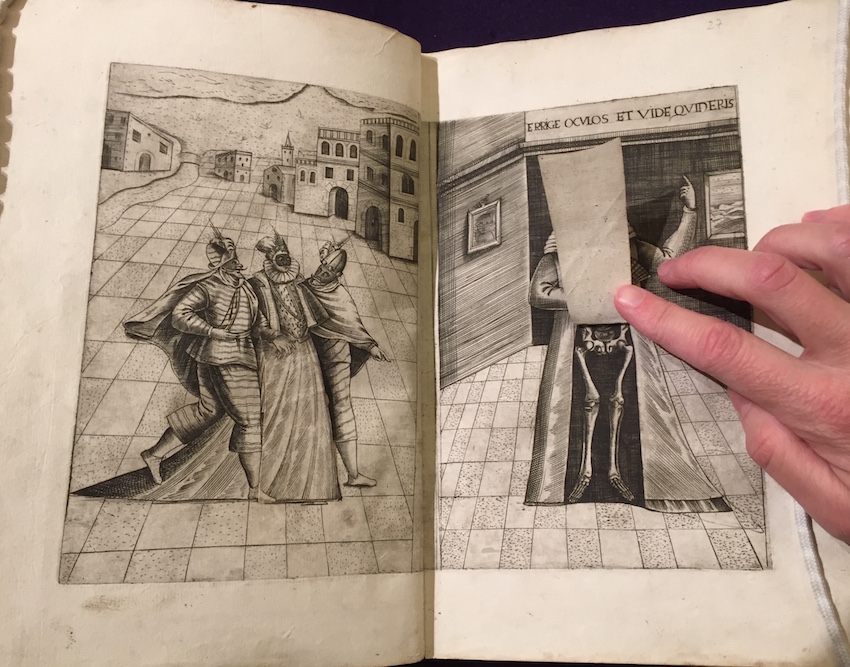

The first 3D page in the book (c. 26-27) depicts two men in rich clothing and feathered hats in the act of leading by the arm a sumptuously dressed and masked woman. The woman’s dress has a flap that can be lifted to reveal the short skirt and the platform shoes (pianelle) underneath it.

Intriguingly, this first depiction of a courtesan is contrasted with a moralistic warning, presented in the page right next to it: “Erige oculos et vide quid eris” (“Raise your eyes and see what you will be”) says the young woman on the opposite page (on the right side for the onlooker) to the festive trio featured in the previous page (on our left). Significantly, her dress has a flap, too: but instead of disclosing an alluring image, the flap on her gown reveals a skeleton.

Is this image just a memento mori, or is it also related to the contemporary anti-courtesan satires, caustic writings wherein satirists took their pleasure in warning courtesans that their present beauty and opulence had an expiration date, and that nothing more than a future of misery and repentance awaited them? Be it as it may, the moral warning of the first depiction of courtesan seems to have no effect on the following pages, where seemingly respectable scenes eventually show themselves in all their scandalous nature.

In the page that comes immediately after (c. 28) a courtesan stands on the shore of the laguna, accompanied by a blindfolded Cupid ready to shoot an arrow of passion. The flap on the courtesan’s dress exposes the full extent of her lasciviousness: she is not only wearing pianelle, but male breeches as well, a reference to the controversial cross-dressing practices that were in vogue among Venetian courtesans.

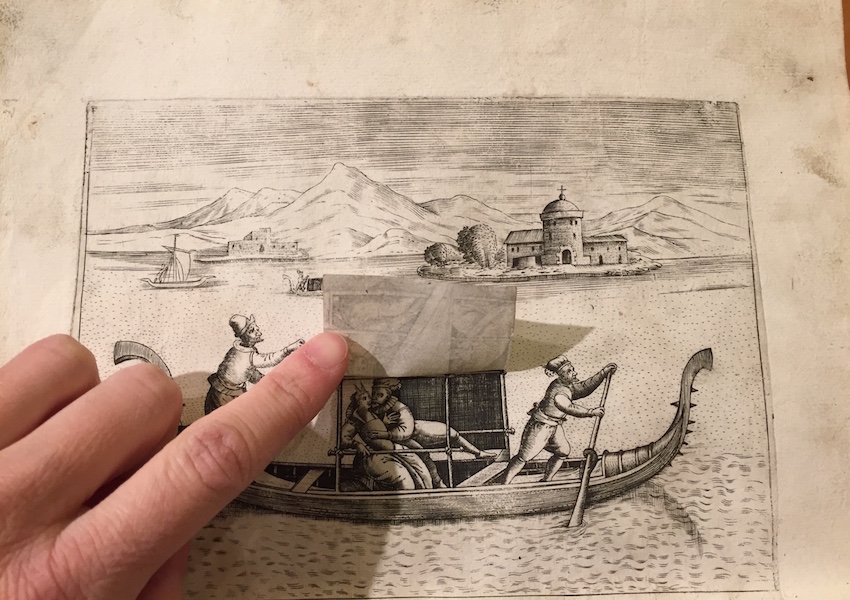

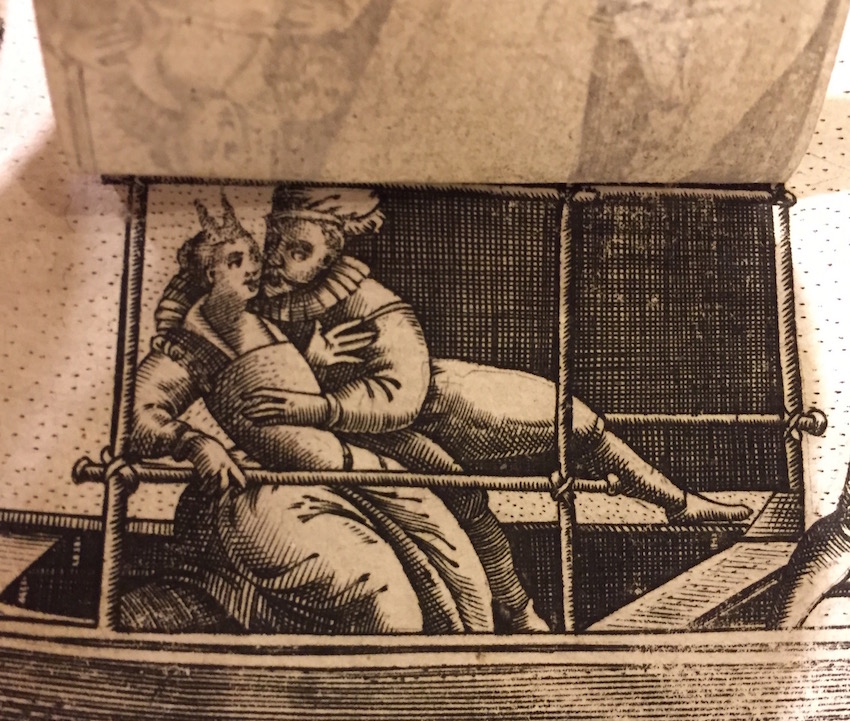

The images that follow offer more examples of what look like perfectly appropriate civic scenes but that, upon lifting the flap, are disclosed to be scandalous views of courtesans and their suitors. The page right opposite the portrait of the courtesan with the cupid presents a gondola scene, with the apparently innocent picture of an elegantly dressed young woman travelling with an old matron (c. 29).

The flap—which turns into tangible tridimensional reality the picted image of the curtain that covers the gondola—reveals instead the passengers to be a courtesan and a man embracing and kissing rather explicitly.

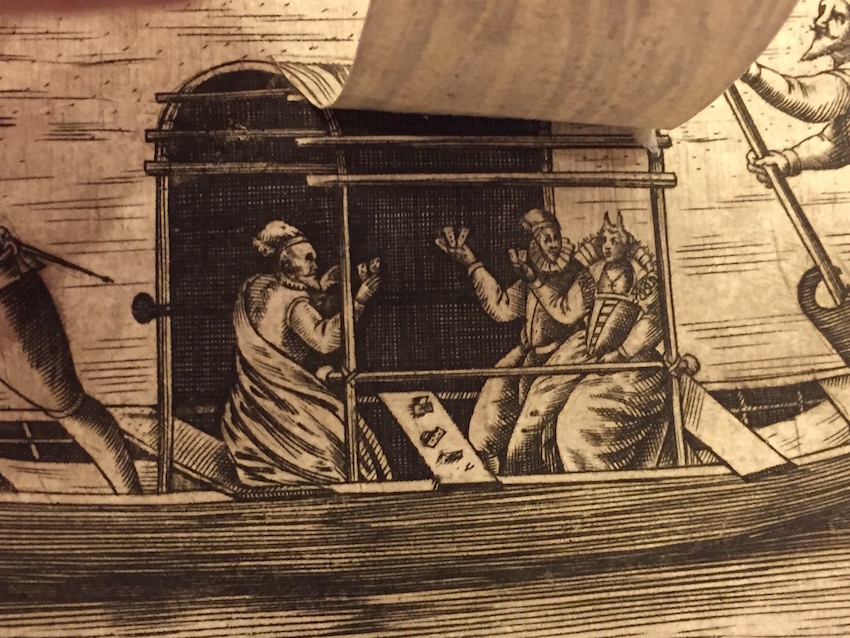

A similar topic is the subject of the image set two pages forward (c. 31), where, again, a gondola partly hidden by a curtain can be unveiled as being the hiding place of two men playing cards with a courtesan.

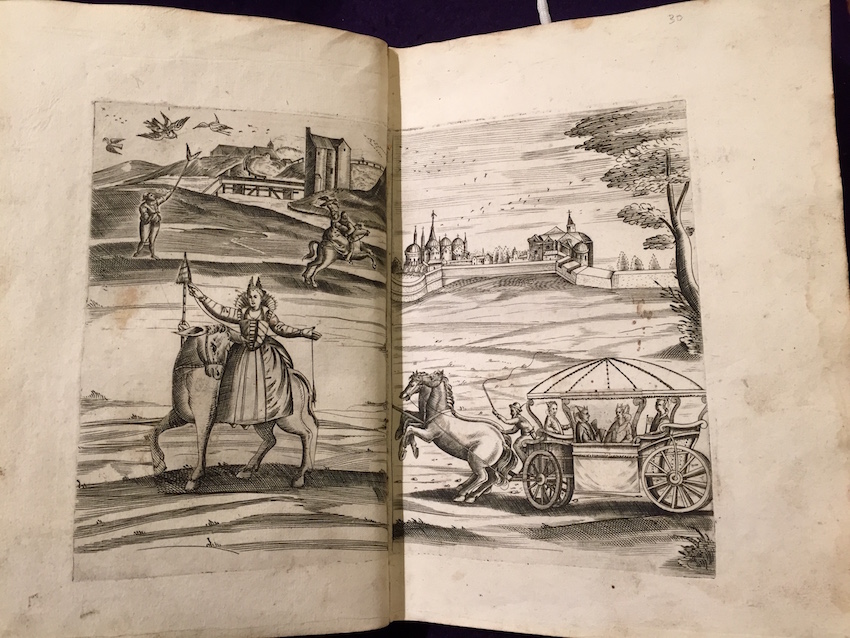

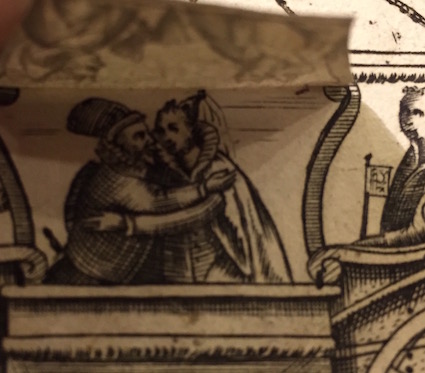

An additional kissing scene is featured in the page that precedes this one (c. 30): a carriage has replaced the gondola, but once more the decent conversational scene among travellers can be unmasked as a lascivious embrace.

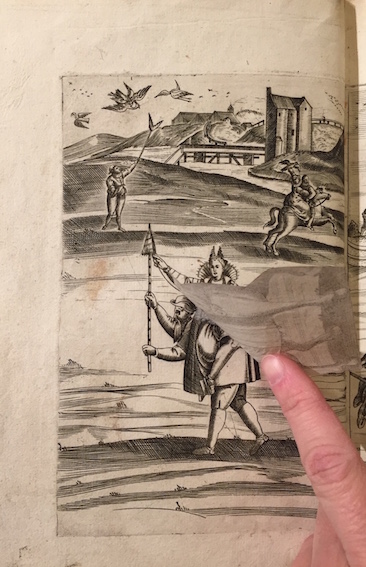

Particularly intriguing is the picture opposite the carriage scene (c. 29)—a sort of “Triumph of the Courtesan” wherein she is presented riding a mule in a docile pose that the flap mercilessly exposes as a man; most likely a reference to the state of subjugation in which, according to the contemporary satiric writings mentioned above, the courtesans brought their suitors.

One final reflection worth making is that the flaps also become a means to denounce similarities between the scandalous courtesan and the perfectly respectable Venetian married woman (“nupta veneta”), who is represented among the portraits in the third and last section of the book (c. 34). As can be seen by confronting their depictions, the married woman and the courtesan in Venice share many similarities in dress and hairdo.

Such similarities would make them, if it was not for the revealing action of the flap, virtually indistinguishable—something that does not seem to affect women in Rome, as can be seen by comparing the pictures of the Roman maiden (“puella Romana”) and of the Roman courtesan (“meretrix Romana”).

In the case of Venetian courtesan, the flap shows the courtesan’s real nature and takes away from her every pretense of good repute. Thanks to its 3D feature, the book leads the reader to discover an outrageous truth hidden under a veil of respectability. And yet, despite all of its warnings against the dangers of associating with the courtesans, Bertelli’s Le vere imagini et descritioni, precisely in virtue of its very use of three-dimensional features, does overall much more to entice its readers than to scare them away from the courtesan. The flaps invite readers to amuse themselves with the courtesan, in a game of innuendos and of hide and seek that mirrors what courtesans and suitors would have done during their real-life encounters.

In Bertelli’s book, the 3D technique of the flap is a way to go—literally!—beyond the surface, and to discover (and, let us not forget, to play with) the scandals that lurk beyond the reputable façade of the city.

For further information on Le vere imagini et descritioni delle più nobilli citta del mondo, see the page from the recent exhibit at NYLP.

All the images in this post are taken from the copy preserved at NYPL.

Further images from the same copy can be seen here and here.