After the studies in mathematics at the universities of Leipzig and Vienna, Peter Bienewitz, latinized into Apianus or Apian, established himself in Landshut where in 1524 he produced his first work of major importance, the Cosmographicus Liber Petri Apiani Mathematici Studiose Collectus (Landshut 1524).

The 1524 publication was a modest success, but after some expanded editions by Gemma Frisius, a Dutch student of Apian, Cosmographicus Liber became a best seller, being reprinted more than 30 times and translated in 14 languages throughout the sixteenth century. Apian’s talent and his book brought him the appointment as professor of Mathematics at the University of Ingolstadt in 1527, where he continued to develop his research and his business as printer – his work culminating with an appointment in the 1530s as one of Charles V’s favourite court mathematicians.

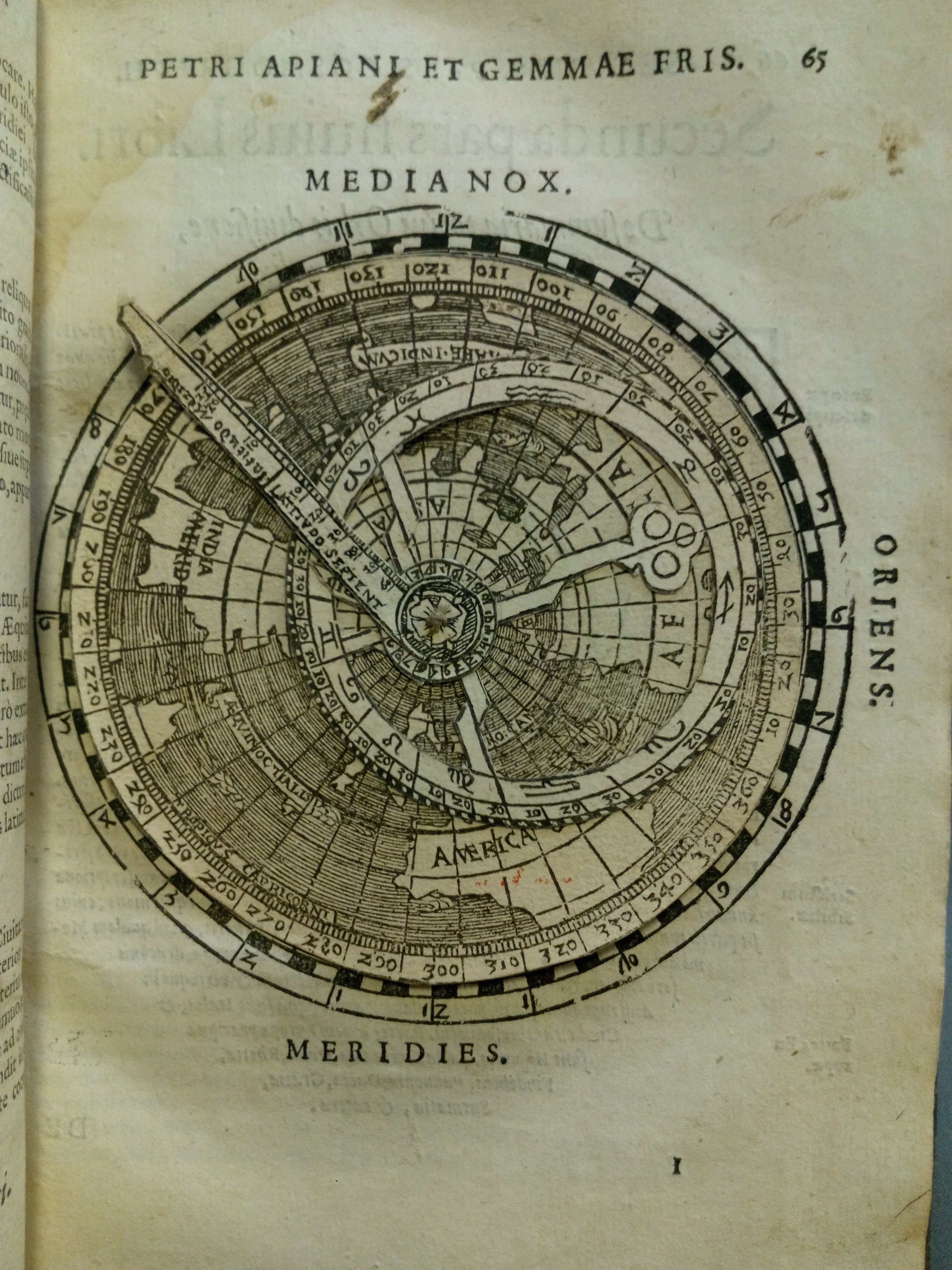

Largely based on Ptolemy, Apian’s Cosmography applies land and building surveying, map projections and instrument making to varied but related disciplines such as astronomy, geography, cartography, navigation. Like all other works by Apian, the approach to these disciplines is practical aiming to solve actual problems.

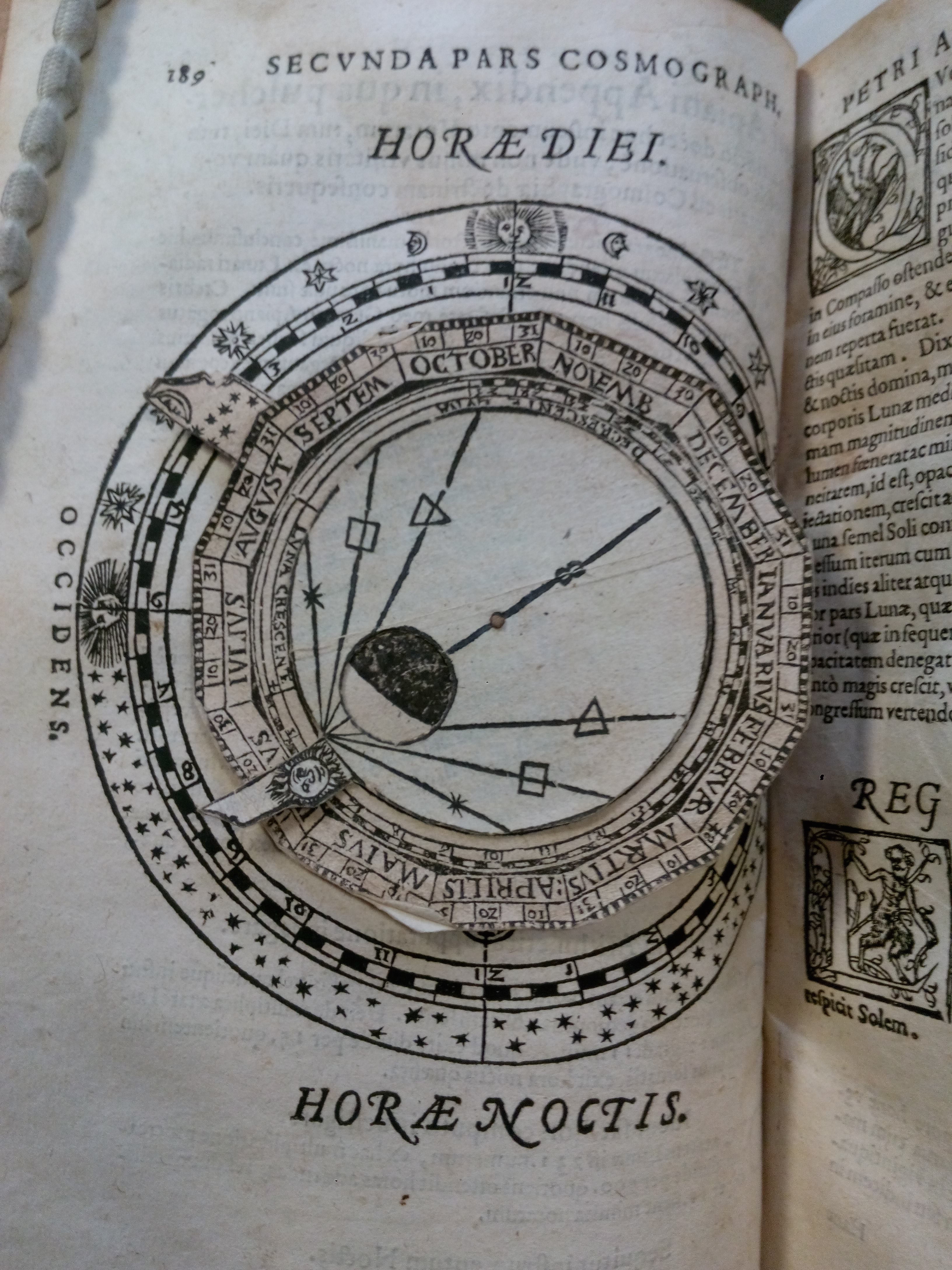

Despite this functional aspect, the book was lavishly illustrated and crafted with the highest attention by the author himself. In fact, Apian worked also as printer in Ingolstadt, beginning with a small workshop, which soon became well known for the high-quality editions, such as the Quadrans. Huic adiuncta et alia instrumenta observatoria perinde nova (Ingolstadt: Peter Apian, 1532), the Folium populi. Instrumentum hoc a Petro Apiano (Ingolstadt: Peter Apian, 1533), and his masterpiece, the Astronomicum Caesareum (Ingolstadt: Peter Apian, 1540).

Apian was as pioneering in the book trade as he was in mathematics and astronomical and geographical instrumentation. He developed and adapted the medieval practice of volvelles, later known also as “Apian wheels”, which implemented rotating parts and slide charts that were real working paper instruments. With the volvelles provided in the Cosmography, one could solve calendar problems, find the position of the sun, moon and the planets, and calculate latitude using the sun’s height above the horizon. A small number of copies of the Cosmography, like the one preserved at the University of St Andrews Library, still conserve two removable templates, a plate and a dial, which once assembled affixed to each other would create a nocturnal clock. The copy at St Andrews has some broken parts, but the many re-issues and new editions maintained the rotating mechanisms.

Astronomers and geographers usually crafted paper instruments, such as quadrants or astrolabes, but Apian was the first one to reproduce them in print – effectively being the first mass-producer of scientific instruments and opening new possibilities in accompanying the instruments with explanatory texts and disseminating them to a broader public.

Apian wheels were a revolution not only for books on astronomy, which increasingly included volvelles on their pages beginning with the editions of Medieval astronomers such as Sacrobosco, but also in the involvement of the readers, who could experiment and engage with the ideas described in the text, and test the perfection of Apian’s instruments.

This was a cunning step for an instrument inventor and manufacturer such as Apian, who used his books as advertisement for his products. With the paper instruments included in the pages of his books, Apian provided the readers with a model of the real instruments he could produce, showing how they looked, how their single parts were designed, assembled, and finally how they would work together. At the same time, the readers had the possibility to practise with the paper instruments in solving different problems, thus realizing the utility of more substantial instruments made of brass and wood.

Further reading

Roettel, Karl (ed.). Peter Apian: Astronomie, Kosmographie und Mathematik am Beginn der Neuzeit. Eichstaett: Polygon-Verlag, 1995.

Wattenberg, Dietrich. Peter Apianus und sein Astronomicum Caesareum. Leipzig: Edition Leipzig, 1967.

Fully digitised copy of the 1524 edition available here.

See also, for reference, here: O’Connor, John J. & Robertson, Edmund F. Petrus Apianus, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

Entry on Petrus Apianus in the website of the Museo Galileo, Florence, with links to entries on astronomical instruments.

Entry on Paper Instruments in the website of the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.